Self-Care Deficit Theory of Nursing in Practice: APN

advertisement

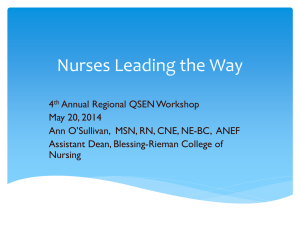

Self-Care Deficit Theory Running head: SELF-CARE DEFICIT THEORY IN PRACTICE Self-Care Deficit Theory of Nursing in Practice: APN Expert Coaching and Guidance in Heart Failure Emily Duke Koch University of Virginia School of Nursing On my honor as a student, I have neither given nor received aid on this assignment. 1 Self-Care Deficit Theory 2 Abstract Heart failure is a chronic illness characterized by periods of exacerbation and remission, and coping with heart failure greatly impacts self-care demands. As proposed in the selfcare deficit theory of nursing, heart failure patients enter periods of fluctuating illness and health states that correspond with varying degrees of self-care deficit and agency. The APN intervention of expert coaching and guidance creates a dynamic, collaborative relationship with patients with the goal of restoring their self-care abilities and preventing heart failure exacerbation and hospitalization. In the process of expert coaching and guidance, the APN integrates self-reflection and clinical expertise with patients’ understandings, experiences and goals to accomplish therapeutic and educational goals. The congruence between nursing theory and practice is realized in the relationship between the self-care deficit theory of nursing and the APN intervention of expert coaching and guidance. Heart failure patients experience a higher level of self-care agency as a result of expert coaching and guidance from an APN. Self-Care Deficit Theory 3 Self-Care Deficit Theory of Nursing in Practice: APN Expert Coaching and Guidance Introduction Heart failure is a chronic illness characterized by periods of exacerbation and remission. Although severely decompensated heart failure may require hospitalization, it is possible for patients to manage heart failure in the outpatient setting and learn to identify the symptoms that indicate decompensation before emergency occurs. Coping with heart failure greatly impacts self-care demands, and as proposed in the self-care deficit theory of nursing, patients enter periods of fluctuating illness and health states that correspond with varying degrees of self-care deficit and agency. The Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) is uniquely prepared to assist patients with heart failure recover and maintain self-care agency. The APN intervention of expert coaching and guidance creates a dynamic, collaborative relationship with patients with the goal of restoring their selfcare abilities and preventing heart failure exacerbation and hospitalization. This paper will discuss the relationship between the self-care deficit theory of nursing and the APN intervention of expert coaching and guidance. It will begin with a description of the clinical nursing problem of heart failure patients’ frequent hospitalization when their self-care deficits outweigh their self-care abilities. Summary of the self-care deficit theory of nursing and description of the expert coaching and guidance intervention will follow. Finally, the paper will discuss the relationship between the theory and the intervention. The congruence between nursing theory and practice is realized in the relationship between the self-care deficit theory of nursing and the APN intervention of expert coaching and guidance. Self-Care Deficit Theory 4 Clinical Nursing Problem Heart failure affects millions of Americans and is the most common reason for hospital admissions among the elderly, accounting for over one million admissions and costing $20 billion per year (Mueller, Vuckovic, Knox, & Williams, 2002; Stanley, 1997). Heart failure consumes copious health care resources, is the foremost complication of heart disease, and is associated with high incidence of early and frequent rehospitalization (Kegel, 1995). The majority of hospitalizations result from decompensation of chronic heart failure, and data suggest about half of these readmissions could be prevented (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002; Mueller, Vuckovic, Knox, & Williams, 2002). Managing heart failure requires careful and frequent patient self-assessment for signs and symptoms of exacerbation and prompt treatment to prevent hospitalization (Kegel, 1995). Thus patients must be actively involved with their plan of care and need access to ongoing education, assessment, and counseling (Kegel, 1995). The greatest barriers to self-care are inadequate knowledge and understanding of disease process and prescribed treatment, inadequate access to healthcare providers, and inadequate social support (Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003; Mueller, Vuckovic, Knox, & Williams, 2002; Stanley, 1997). Following hospitalization for heart failure exacerbation, key clinical problems leading to preventable rehospitalizations are inadequate patient and family education, poor self-assessment skills, inadequate support systems, failure to seek medical attention promptly when symptom reoccur, and noncompliance with diet and medication regimens (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002; Stanley, 1997). One way to prevent Self-Care Deficit Theory 5 hospitalizations and to promote positive health outcomes in heart failure patients is to ensure that the amount and quality of self-care used is appropriate for individual patients’ conditions (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002). Substantial evidence suggests that frequent hospitalizations for heart failure exacerbation can be prevented by Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) intervention and coordinated disease management strategies (Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003; Kegel, 1995; McCauley, Bixby, & Naylor, 2006; Stanley, 1997). APNs are particularly adept at facilitating self-management of heart failure by collaborating with and coordinating care among care providers, providing education and planning to prepare hospitalized patients for discharge, following up with discharged patients, assessing access to resources, maintaining presence in the lives of heart failure patients, and establishing therapeutic partnerships with patients and families (Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003; Kegel 1995; McCauley, Bixby, & Naylor, 2006). When heart failure patients’ self-care abilities overwhelm their self-care deficits, it is possible to prevent hospitalization and manage heart failure in outpatient setting. Summary of the Theory Purpose This paper will use Chinn & Kramer’s (2008) guide to describe the self-care deficit theory of nursing (Orem, 2001). Orem’s work on the self-care deficit theory of nursing began in the 1950s when nursing curricula were based on conceptual models from medicine, psychology, and sociology (Fawcett, 2001). She was motivated by the desire to foster agreement about the proper focus of nursing and the need to clarify the Self-Care Deficit Theory 6 domain and boundaries of nursing practice (Orem, 2001). Orem felt that nursing lacked an organizing framework for its knowledge and hoped that formal articulation of the foundations and essential elements of the self-care deficit theory of nursing would serve to upgrade nursing education curriculums and enhance nursing’s disciplinary evolution (Fawcett, 2001). The self-care deficit theory of nursing asserts that human limitations in self-care associated with states of illness give rise to the requirement for nursing care (Fawcett, 2001). Orem refined and formally described what nursing is and should be in the selfcare deficit theory of nursing, which has three constituent articulating theories: (a) the theory of self-care, which describes why and how people care for themselves; (b) the theory of self-care deficit, which explains why people require nursing; and (c) the theory of nursing systems, which describes relationships that must be fostered and maintained for effective nursing care (Fawcett, 2001; Orem, 2001). The self-care deficit theory of nursing is a general theory, applicable across all nursing practice areas and situations in which people require nursing care (Orem, 2001). According to the self-care deficit theory of nursing, the special focus on human beings is what distinguishes nursing from other human services (Orem, 2001). It follows that the role of nursing in society is to assist individuals’ development and exercise of their self-care abilities to the extent that they can adequately and completely provide for their care requirements (Isenberg, 2001). According to the theory, individuals who cannot adequately provide for their self-care requirements are experiencing a self-care deficit, and it is this deficit that identifies individuals in need of nursing care. The theory’s Self-Care Deficit Theory 7 purpose in formulating the self-care deficit theory of nursing is to describe when and why nursing is needed (Isenberg, 2001). Concepts The self-care deficit theory of nursing implies two categories of human beings: the agent of action and the object of action (Denyes, Orem, & SozWiss, 2001). The three interrelated theories of the general self-care deficit theory of nursing identify and define four concepts about individuals who require nursing care: self-care, self-care agency, therapeutic self-care demand, and self-care deficit. The theory identifies and defines two concepts about those who provide nursing service: nursing agency and nursing systems. Orem proposes that human beings throughout the lifespan have self-care agency, which she defines as the power to develop and exercise capabilities to know and meet self-care requirements (Orem, 2001). According to the theory, self-care agency varies qualitatively and quantitatively throughout the lifespan, and a self-care deficit exists when, for health and health-care associated reasons, individuals’ self-care agency proves incapable of meeting therapeutic self-care demands (Orem, 2001). The imbalance between a person’s self-care agency and therapeutic self-care demand creates the need for nursing care. Nursing agency is defined as the power of nurses to design and produce nursing care for others. It follows that nursing agency extends to assist individuals with health-associated self-care deficits to know and meet with assistance their self-care demands and to exercise their powers of self-care agency (Orem, 2001). In the latest edition of the self-care deficit theory of nursing, nursing is recognized as a tripartite nursing system comprised of a professional-technical system dependent on an interpersonal system and a societal system that provide the context for the nurse- Self-Care Deficit Theory 8 patient relationship (Orem, 2001). The nursing system concept describes the evolution of nursing to include details of the structure and process of providing nursing care to individuals, families, and communities (Orem, 2001). Nurses make decisions about what type of nursing system is appropriate to attend to a self-care deficit by asking who can and should perform the self-care operations (Isenberg, 2001). The nurse then designs and applies the appropriate system with the goal of empowering the person to meet their selfcare requirements. The continuum of nursing systems range from wholly compensatory if the nurse provides for the self-care demand to supportive-educative if the nurse assists the individual to develop agency, with a partly compensatory system falling in between the two extremes when nurses both provide for and assist the patient to provide for selfcare demands (Isenberg, 2001). Relationships, Structure, and Assumptions The self-care deficit theory of nursing describes and explains the relationship between self-care agency and therapeutic self-care demand, identifying a self-care deficit when capabilities to engage in self-care are less than the demand for self-care (Isenberg, 2001). The theory states that nurses provide a therapeutic system when individuals are identified with an existing or potential self-care deficit. The theory’s conceptual framework treats the concept of the whole person as greater than the sum of the parts. For Orem, the individual is an integrated whole person with varying degrees of self-care capabilities informed by the individual’s internal physical, psychological, and social nature (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). The theory assumes that restoration of self-care agency is the desired goal and purpose of nursing. Additionally, the theory assumes individuals are motivated by self-preservation to participate in the restoration of self-care agency. Self-Care Deficit Theory 9 Application of the Theory: Nursing Care of Patients with Heart Failure The theory implies that nursing actions are required to restore self-care ability and provides comprehensive development of the self-care concepts, rendering the theory applicable and useful as a guide to nursing practice areas involving individuals across the lifespan experiencing health or illness, as well as to nursing interventions designed for health promotion, health restoration, and health maintenance (Isenberg, 2001). The theory’s application to nursing practice is well documented in the literature across a wide range of age groups, practice settings, and nursing systems of care (Isenberg, 2001). This paper will consider the theory’s relevance to the heart failure patient population, which is also well documented in the literature. Description of the APN Intervention: Expert Coaching & Guidance Coping with heart failure greatly impacts self-care demands, and as proposed in the self-care deficit theory of nursing, patients enter periods of fluctuating illness and health states that correspond with varying degrees of self-care deficit and agency. The Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) is uniquely prepared to assist patients with heart failure recover and maintain self-care agency. Expert coaching and guidance is an APN core competency and describes a complex, invisible process wherein the APN provides education, surveillance, and reassurance to equip patients with the tools to manage their health and illness transitions (Spross, 2009). Spross defines APN coaching as “a complex, dynamic, collaborative and holistic interpersonal process that is mediated by the APN-patient relationship and the APN’s self-reflective skills” (Spross, 2009, p. 167). In the process of expert coaching and guidance, the APN integrates self-reflection and clinical expertise with patients’ understandings, experiences and goals to accomplish Self-Care Deficit Theory 10 therapeutic and educational goals (Spross, 2009). The interaction of self-reflection with technical, clinical, and interpersonal competence (Figure 1) drives the expansion and refinement of the APN’s expertise in this process (Spross, 2009). The intervention is termed coaching and guidance because these terms imply the existence of a relationship that is fundamental to effective patient education and teaching (Spross, 2009). A coach facilitates safe passage through transition, and the work of coaching is complex and requires interpersonal confidence and competence. In the model of APN expert coaching and guidance, the APN integrates physical examination, interviewing, and intuition to acquire the patient’s perspective and reflect or translate this understanding back to the patient (Spross, 2009). The APN involves the patient’s significant other as appropriate. As coach, the APN helps patients uncover opportunities for personal growth and assists them to clarify goals, decide what matters most to them, acknowledge trade-offs and losses, and develop coping strategies (Spross, 2009). The term coaching applied to the nurse-patient relationship permits both parties to experience intense emotion and it simultaneously connotes the one-sided aspect and mutuality in the relationship (Spross, 2009). Coaching is multidimensional involving cognitive, spiritual, behavioral, physical, and social aspects of the human experience, and competence in its administration requires a tailored approach to meet each individual patient’s needs (Spross, 2009). In the setting of heart failure, the APN can provide expert coaching and guidance to address patient self-assessment, adherence to medication and diet regimen, knowledge of disease maintenance, social support, and resource utilization (Kegel, 1995; McCauley, Bixby, & Naylor, 2006). The APN is uniquely equipped with advanced communication Self-Care Deficit Theory 11 skills to build therapeutic relationships with patients. The APN can elicit the patient’s thoughts, perspectives, expectations, values, and goals; provide patients with self-care information to enable participation in health decisions; and develop disease management plans collaboratively with patients (Spross, 2009). The APN can conduct individualized patient assessment to identify signs and symptoms of heart failure exacerbation and teach the patient how to problem solve and identify emergency (McCauley, 2006). The education plan in the expert coaching and guidance model considers the patient’s knowledge base, learning style, and capabilities. It is important for patients to understand the importance of adhering to disease maintenance regimen even when symptoms subside (McCauley, 2006). APNs use multiple strategies to improve patients’ self-management including education about the chronic nature of heart failure, practical solutions such as pill organizers and patient-specific prompts to remember to take them, detailed nutrition counseling sessions (McCauley, 2006). The APN uses patient-centered communication to learn the patient’s beliefs about their illness and treatment, perceptions of severity of the condition because studies have shown that the patient’s subjective interpretation of the severity of disease is often more influential than objective reality (Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003; Spross, 2009). The effectiveness of telemanagement as a component of the expert coaching and guidance intervention is well-documented in the literature (Kegel, 1995; Mueller, Vuckovic, Knox, & Williams, 2002; Ryder, 2005). This is a particularly effective strategy for reinforcing and clarifying how to take and follow medication regimen and disease management strategies that a patient may have received at time of discharge from Self-Care Deficit Theory 12 the hospital or during a physician visit. Patients experiencing heart failure decompensation are under duress and typically forget two thirds of diagnosis and treatment explanations and half of instructional statements immediately after physician visit (Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003). Discussion of the Theory as Supportive of the Intervention Since heart failure is a chronic disease characterized by exacerbations and disease maintenance, self-care is important to optimize outcomes. Self-care behaviors include adherence to medication and diet regimen, seeking assistance when symptoms indicate exacerbation, and performing daily weights (Kegel, 1995; McCauley, 2006). The selfcare deficit theory of nursing identifies three sets of limitations for self-care: limitations of knowing, limitations of judgment, and limitations on result-achieving courses of action (Orem, 1995). All three sets of limitations are present to varying degrees in heart failure patients. The nursing system that seems to be most applicable for addressing these limitations for maintenance of heart failure is the supportive-educative system. The selfcare deficit theory of nursing describes general methods of nursing action in the supportive-educative system, including support, guidance, provision of developmental environment, and teaching (Orem, 1995). Several articles documented Orem’s general theory as a framework for studying, describing, and developing supportive-educative nursing interventions to prevent potential self-care deficits and enhance self-care agency for heart failure patients in the outpatient setting (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002; Jaarsma, Abu-Saad, Dracup, & Halfens, 2000; Jaarsma, Halfens, Senten, Saad, & Dracup, 1998). Self-Care Deficit Theory 13 Coping with heart failure greatly impacts self-care demands (Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003). Phases of adjusting to heart failure include acceptance, adjustment to crisis and diagnosis, and decision to resume living with new knowledge of the condition (Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003). APNs can promote self-care by providing information within a supportive-educative framework that is consistent with the individual’s phase of adjustment. In particular, an Orem-inspired supportive-educative nursing system has facilitated several programs designed to enhance patients’ abilities to perform self-care operations to maintain a prescribed medication regimen and to monitor and manage symptoms (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002; Fujita & Dungan, 1994; Schneider, Hornberger, Booker, Davis, Kralicek, 1993). One example is the utilization of a diuretic treatment algorithm, in which APNs and patients agree on a set of signs and symptoms of decompensation for the patient to use to determine when to take an extra dose of diuretic and when to see a physician (Meuller, Vuckovic, Knox, & Williams, 2002). During periods of exacerbation and in the instance of end stage heart failure patients who are under consideration for heart transplant, the wholly compensatory and partly compensatory nursing systems become more applicable, but these scenarios are less documented in the literature. Casida, Peters, & Magnan (2009) eloquently propose the use of self-care deficit theory of nursing as a framework to identify and organize nursing care for hospitalized heart failure patients on left-ventricular assist devices and to assess readiness for discharge. In the expert coaching and guidance intervention, the APN individualizes strategies for changing health behaviors, fosters initiative, encompasses an unambiguous Self-Care Deficit Theory 14 treatment plan, and incorporates patients’ significant others (Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003). Evidence suggests that APN expert coaching and guidance, in conjunction with coordinated care and collaboration among providers can decrease hospital readmission in heart failure patients by as much as 50% (Mueller, Vuckovic, Knox, & Williams, 2002). Through expert coaching and guidance, the APN uses multiple strategies to simultaneously address heart failure patients’ limitations of knowing, limitations of judgment, and limitations of result-achieving courses of action (McCauley, 2006). Significant increases in self-care agency occur when education and support are provided and when patients perceive themselves to be a partner in the development of their treatment plans (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002). Concluding Summary of the Relationship Between the Theory and the Intervention The congruence between nursing theory and practice is realized in the relationship between the self-care deficit theory of nursing and the APN intervention of expert coaching and guidance. The expert coaching and guidance APN intervention is a perfect practical application of the self-care deficit theory of nursing. The goal of the expert coaching and guidance intervention is to restore patients’ ability to provide for their selfcare needs. As coach, the APN helps patients discover opportunities for personal growth and assists them to clarify goals, decide what matters most to them, acknowledge tradeoffs and losses, and develop coping strategies (Spross, 2009). The APN coach can equip heart failure patients with the knowledge and tools to recognize their self-care agency and self-care deficits. Heart failure is characterized by exacerbations and remissions (Stanley 1997). Coping with heart failure greatly impacts self-care demands, and as proposed in the self- Self-Care Deficit Theory 15 care deficit theory of nursing, patients enter periods of fluctuating illness and health states that correspond with varying degrees of self-care deficit and agency. The Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) is uniquely prepared to assist patients with heart failure recover and maintain self-care agency. By maintaining the commitment to the coaching and guidance process, the APN establishes a supportive and therapeutic partnership with heart failure patients that allows for fluctuations in the patient’s ability to self-manage a labile chronic disease in the outpatient setting (Ryder, 2005). The APN coach can expertly individualize strategies in accordance with patients’ varying degrees of confidence, fear, knowledge, abilities, and resources within a supportive-educative nursing framework (Orem, 1995; Spross, 2009). Increases in self-care behaviors as a result of expert coaching and guidance from an APN are well-documented in the literature (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002; Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003; McCauley, 2006; Ryder, 2005). Specifically, after APNs addressed self-care limitations, heart failure patients demonstrated improved and effective self-care decision making in response to signs and symptoms of heart failure exacerbation, promptly and appropriately seeking medical care (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002; Davidson, Macdonald, Paull, Rees, Howes, Cockburn, & Brown, 2003). Additionally, heart failure patients demonstrated improved understanding of their disease process and better selfmanagement relative to medication compliance and weight monitoring in response to APN expert coaching and guidance interventions (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002). Self-Care Deficit Theory 16 The relationship between knowledge and self-care behavior is significant and documented throughout the literature without exception, revealing the practical application of the self-care deficit theory of nursing. The theory proposes that knowledge is a power that enables self-care and that strategies to address knowledge limitations must be specific and organized around known self-care requisites (Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002). The APN intervention of expert coaching and guidance is uniquely suited to apply the self-care deficit theory in practice. Through the intervention of expert coaching and guidance, the APN considers the patient’s knowledge base, learning style, and capabilities to develop disease management plans collaboratively with patients (McCauley, 2006; Spross, 2009). Heart failure patients experience a higher level of selfcare agency as a result of expert coaching and guidance from an APN. Self-Care Deficit Theory 17 References Anderson J. H. (2007). The impact of using nursing presence in a community heart failure program. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 22 (2), 89-94. Artinian, N. T., Magnan, M., Sloan, M. & Lange, M. P. (2002). Self-care behaviors among patients with heart failure. Heart & Lung, 31 (3), 161-172. Casida, J. M., Peters, R. M., & Magnan, M. A. (2009). Self-care demands of persons living with an implantable left-ventricular assist device. Research & Theory for Nursing Practice, 23 (4), 279-293. Chinn, P. L. & Kramer, M. K. (2008). Integrated Theory and Knowledge Development in Nursing (7th ed.). St. Louis: CV Mosby. Davidson, P., Macdonald, P., Paull, G., Rees, D., Howes, L., Cockburn, J., & Brown, M. (2003). Diuretic therapy in chronic heart failure: Implications for heart failure nurse specialists. Australian Critical Care, 16 (2), 59-69. Denyes, M. J., Orem, D. E., & SozWiss, G. (2001). Self-care: A foundational science. Nursing Science Quarterly, 14 (1), 48-54. Fawcett, J. (2001). Scholarly dialogue: The nurse theorists: 21st century updates – Dorothea E. Orem. Nursing Science Quarterly, 14 (1), 34-38. Fujita, L. Y. & Dungan, J. (1994). High risk for ineffective management of therapeutic regimen: a protocol study. Rehabilitation Nursing, 19 (2), 75-79, 126. Isenberg, M. A. (2001). Part two: Applications of Dorothea Orem’s self-care deficit nursing theory. In Parker, M. (Ed.), Nursing theories and nursing practice (2nd ed., pp. 149-159). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. Self-Care Deficit Theory 18 Jaarsma, T., Abu-Saad, H. H., Dracup, K., & Halfens, R. (2000). Self-care behavior of patients with heart failure. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 14 (2), 112119. Jaarsma, T., Halfens, R., Senten, M., Saad, H. H. A., & Dracup, K. (1998). Developing a supportive-educative program for patients with advanced heart failure within Orem’s general theory of nursing. Nursing Science Quarterly, 11 (2), 79-85. Kegel, L. M. (1995). Advanced practice nurses can refine the management of heart failure. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 9 (2), 76-81. McCauley, K. M., Bixby, M. B., & Naylor, M. D. (2006). Advanced practice strategies to improve outcomes and reduce costs in elders with heart failure. Disease Management, 9 (5), 302-310. Mueller, T. M., Vuckovic, K. M., Knox, D. A., & Williams, R. E. (2002). Telemanagement of heart failure: A diuretic treatment algorithm for advanced practice nurses. Heart & Lung, 31 (5), 340-347. Orem, D. E. (2001). Part one: Dorothea E. Orem’s self-care deficit nursing theory. In Parker, M. (Ed.), Nursing Theories and Nursing Practice (2nd ed., pp. 141-149). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. Orem, D. E. (1995). Nursing: Concepts of Practice. St. Louis, MO: Mosby. Ryder, M. (2005). Is heart failure nursing practice at the level of a clinical nurse specialist or advanced nurse practitioner?: The Irish experience. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 4 (2), 101-105. Schneider, J. K., Hornberger S., Booker, J., Davis, A., & Kralicek, R. (1993). A medication discharge planning program: Measuring the effect on readmissions. Self-Care Deficit Theory Clinical Nursing Research, 2 (1), 41-53. Spross, J. A. (2009) Expert Coaching and Guidance. In Hamric, A. B., Spross, J. A., & Hanson, C. M. (Eds.), Advanced Practice Nursing: An Integrative Approach 4th Edition (pp. 575-604). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. Stanley, M. (1997). Current trends in the clinical management of an old enemy: Congestive heart failure in the elderly. AACN Clinical Issues 8 (4), 616-626. 19 Self-Care Deficit Theory Figure 1. Model of the APN intervention of expert coaching and guidance. 20