League structure optimization

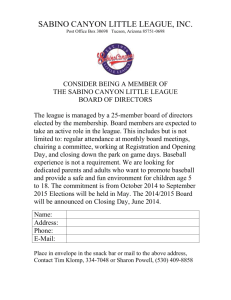

advertisement