PHONOLOGY OF MERNYANG LANGUAGE

advertisement

PHONOLOGY OF MERNYANG

LANGUAGE

OLAGBENRO RASHIDAT BOLA

07/15CB075

A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND

NIGERIAN LANGUAGES, FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN,

ILORIN, NIGERIA.

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD

OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS B. A. (HONS.)

IN LINGUISTICS

MAY, 2011.

1

CERTIFICATION

This project has been read and approved as meeting the requirements of

Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Ilorin, Ilorin,

Kwara State, Nigeria.

_____________________________

DR. M. A. O. OYEBOLA

____________________

DATE

_____________________________

PROF. A. S. ABDUSSALAM

____________________

DATE

_____________________________

EXTERNAL EXAMINER

____________________

DATE

Project Supervisor

Head of Department

2

DEDICATION

I dedicate this research work to the Almighty God, who has been my

anchor and strength and also to my parents Mr. & Mrs. I.O. Olagbenro.

3

ACKNOLWEDGEMENTS

My profound gratitude goes to my supervisor, Dr. M. A. O. Oyebola,

you have been great help to me. I also appreciate the knowledge impacted

in me by my lecturers.

Words are not enough to show gratitude to my parents, Mr. and Mr.

Olagbenro. Their care and support from the day I was born to this moment

is overwhelming. I do wish to line up to your expectations.

I appreciate the understanding and love shown to me by my siblings

– Oyeyemi, Folakemi and Olamide. God’s face will continue to shower upon

you.

My appreciation also goes to Mayowa, Ridwan, Tosin and Fisayo for

their support throughout the journey to plateau state, God bless you all.

I also thank my friends and colleagues: Funke, Olakitike, Olatokunbo,

Bukola Yetunde, Tolu, Habibat, Kenny, Comrade, Sa’aad Rahman, Yusuf

and my typist Agboola Olasunkanmi.

Thank you all.

4

LIST OF SYMBOLS USED

Arrow notation ‘becomes’

/

Environment

____ Place of occurrence

[]

Surface/Phonetic Representation

~

Tilde [nasalization symbol]

Empty/Null Element

+

Morpheme boundary

[/]

High tone

[-]

Mid tone

[\]

Low tone

V

Rising tone

Falling tone

5

LISTS OF CHARTS, TABLES AND DIAGRAMS

Genetic Classification Tree

Oral Vowel Chart

Nasal Vowel Chart

Vowel Distinctive Features Matrix

Phonetic Consonant Chart

Consonant Distinctive Features Matrix

6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

i

Certification

ii

Dedication

iii

Acknowledgments

iv

List of Symbols

v

List of Charts, Tables and Diagrams

vi

Table of Contents

vii

CHAPTER ONE:

1.0

Introduction

1

1.1

General Background

1

1.2

Historical Background

2

1.3

Socio-Cultural Profile

4

1.3.1 Marriage System

4

1.3.2 Mode of Kinship

5

1.3.3 Religion

6

1.3.4 Occupation

6

7

1.3.5 Food

7

1.3.6 Housing

7

1.3.7 Dressing

7

1.3.8 Geographical Location

8

1.3.9 Festivals

8

1.4

Scope and Organization of the Study

9

1.5

Data Collection

10

1.6

Genetic Classification

11

1.7

Data Analysis

13

1.8

Review of Theoretical Framework

13

1.9

Structure of Generative Phonology

14

1.9.1 Phonological Representation

15

1.9.2 Phonetic Representation

16

1.9.3 Phonological Rules

16

CHAPTER TWO:

2.0

Introduction

19

2.1

Basic Phonological Concepts

19

8

2.1.1 Principle of Minimal Pair

20

2.1.2 Phonemes and Allophones

21

2.1.3 Complementary Distribution

22

2.2

Sound Inventory

24

2.3

Tonal Inventory

25

2.4

Syllable Inventory

26

2.4.1 Syllable Structure in Mernyang

27

Sound Distribution

29

2.5.1 Consonant Sounds

29

2.5.2 Consonant Segments in Mernyang

31

2.5.3 Vowels in Mernyang

43

2.5.4 Distribution of Vowels

44

2.5.5 Vowel Nasals

48

2.5

2.5.6 Distinctive Feature Matrix for Mernyang

Language Consonants

50

2.5.7 Justification of the Features Used

53

2.5.8 Segment Redundancy for Consonants

55

9

2.5.9 Distinctive Features Matrix for Vowels

57

2.5.10 Justification of Features Used

57

2.5.11 Segment Redundancy for Mernyang Vowel

58

CHAPTER THREE; PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES

3.0

Introduction

60

3.1

Phonological Processes

60

3.1.1 Assimilation

61

3.1.2 Labialization

63

3.1.3 Palatalization

64

3.1.4 Nasalization

65

3.1.5 Insertion

66

3.1.6 Deletion

67

3.1.7 Vowel Elision

68

CHAPTER FOUR: TONE AND SYLLABLE PROCESSES IN MERNYANG

LANGUAGE

4.0

Introduction

73

4.1

What is a Tone Language?

73

10

4.2

Tone Typologies

74

4.3

Tonal Patterns in Mernyang Language

74

4.3.1 Co-Occurrence of Tones in Mernyang Language

77

4.3.2 Functions of Tones

79

Tonal Processes

80

4.4.1 Tone Hierarchy

80

Syllable Structure

82

4.5.1 Types of Syllable

84

4.5.2 Syllable Structure Rule in Mernyang Language

85

Syllable Processes

88

4.6.1 Types of Syllable Processes

88

4.4

4.5

4.6

CHAPTER FIVE: SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5.0

Introduction

89

5.1

Findings/Observation

91

5.2

Recommendations

91

5.3

Conclusion

92

References

93

11

CHAPTER ONE

GENERAL BACKGROUND

1.0 INTRODUCTION

This chapter introduces the language of study, the people speaking

the language and where they can be found. It also introduces us to the

background of the speakers of the language which includes their way of life

(culture) and their beliefs, it also gives a brief explanation of the scope of

study. Methods of data collection, genetic classification and the theoretical

framework used in carrying out the research on the language are included.

1.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND

Mernyang language is a language spoken in Qua’an-pan local

government of Plateau state. The speakers majorly reside in Kwa while

others reside in other districts like, Kwang, Dokankaswa, Doemak, Namu,

Kwalla and Pwall in this same local government. The estimated population

of the Mernyang speakers is about 5,000 according to 2007 census.

12

Mernyang speakers are referred to as the Pan people, while among

themselves they are known as Mernyang speakers. These people are said

to have migrated from the North East in Dala, Kano State.

1.2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Going by oral history and written record, the Mernyang people are

said to have originated from a group of people known as Kofyar who are

residing on the top of hills in Plateau state in Qua’an-Pan local government.

Dafyar, from whom the Mernyang own their descent is said to have

procreated with his sister Nada, as they were the only survivors of a

cataclysm. This fatal incident made Dafyar and his sister Nade leave Dala

in Kano and sailed on the river to a place where they hid themselves in a

cave called Chor in Kopfubum near the present day Kofyar. Since then,

Dafyar and his offsprings have been residing on the Kofyar hill.

The offsprings of Dafyar had fanned out into many other sub groups

and intermarried thereby producing a much wider cultural mix. The

offspring of Dafyar comprised his sons and grandsons or even great grand

sons and so on.

13

Oral tradition has for long maintained the fourteen (14) who have

been popular due to the settlements that grew in the wake of their earlier

location. Among these sons of Dafyar was Darep, Soekoetko who founded

the ‘Kwa’ settlement which is approximately three kilometers (3km) away

from Kofyar. Darep was the first person to settle in the place known as

‘Kwa’ village today in Qua’an-Pan local government area of Plateau State.

Since then he had been giving birth to children who were and are also

producing sons and daughters such that the current estimated total

population of the speakers of Mernyang is 5,000. The movement of the

Mernyang people form Kofyar to ‘Kwa’ was mainly for agricultural purpose.

The major occupation of the Mernyang people is farming, so they found a

suitable farming land in ‘Kwa’. This made majority of the people in Kofyar

descend and later settle down there. Today, majority of the Mernyang

speakers are found in Kwa.

1.3 SOCIO-CULTURAL PROFILE

14

The Mernyang people like many other tribes have their own unique

cultural lifestyle. The Mernyang people have some unique lifestyle which

are discussed below:

1.3.1 Marriage System

The system of getting married among Mernyang people is interesting,

simple and perhaps less demanding, though systematic. As usual after the

man and the woman who are in love with each other have agreed to marry

each other, the first stage comes in. This first stage, the groom and his

friends will go to the bride’s house in order to reveal his intention of

marrying their daughter to them. The groom would take along two jaws of

local wine which the people call ‘Doeskoelo’ to the bride’s parents.

At this occasion, the bride’s parents would ask their daughter if she is

interested in the marriage. If she does they would ask her to collect the

Jars of ‘Doeskoeloe’ from the groom, signifying she agrees. The second

stage involves the groom’s parents visiting the bride’s parents where the

latter would be asked to supply some items for acceptance that the groom

is free to take their daughter. The items include; goat, chicken, salt, rice,

15

palm oil and benny seed. These items are the major ones required only if

the brides parents want more or less. The third stage has to do with the

bringing of those items by the groom’s family to the bride’s family. Once

accepted, the groom can take his wife home. The fourth and final stage

entails the groom and the bride conducting marriage ceremony either in

the church or mosque depending on the religion of the couple.

1.3.2 Mode of Kinship

The traditional system of ruling among the Mernyang people is

monarchical. That is, another chief (king), known as ‘long’ in Mernyang

language, can assume the throne only if ruling chief dies. However, the

choice of who will be the next chief in the royal family is not the one by

appointment but by election. There would be two or three sons in the royal

family who will compete for the vacant seat. The voting by the royal family

members would determine the next chief. After this, the king makers have

to test the competence of the elected candidate, and if found worthy, then

becomes the chief.

1.3.3 Religion

16

According to oral history, it is believed that the traditional religion of

the Mernyang people was idol worshipping. The advent of foreign

missionaries however brought Christianity and Islam, such that today, idol

worshipping has been eradicated among the people. At present, the

predominant religion among the Mernyang people is Islam. Though there

are few Christians and the existence of festival celebrations.

1.3.4 Occupation

In Kwa, the geographical location of the Mernyang speakers, the

major occupation is farming. Hardly can one look around without seeing

millet and guinea corn plants which are their main plants in the land.

Besides this, others still engage in fishing and hunting in order to make

ends meet. Among food derived from millet or guinea corn is ‘nigum’

grounded with groundnuts, meloni fish and palm oil or even pieces of

meat. This is made into a thick folded corn leaves.

1.3.5 Food

The favourite food items of the Mernyang people are millet and

guinea corn, little wonder that they are mainly millet and guinea corn for

17

consumption,

including

their

favourites

drink

generally

known

as

‘burukutu’. The traditional food of the Mernyang people is beans called

‘bálá’. The food is served to important people.

1.3.6 Housing

A typical Mernyang house is made with mud or clay with grassroofing on top. This type of house is dominant every where in the land.

However, civilization has forced some educated ones among them to build

modern houses, yet lying to be inhabited.

1.3.7 Dressing

The mode of dressing of the Mernyang people is similar to that of the

Hausas. Typically, they are often seen dressed in their native ‘agbada’ with

the popular ‘aburo’ cap. While their women are dressed in ‘buba’ and two

wrappers tied round their waist.

1.3.8 Geographical Location

Speakers of Mernyang language are geographically located at the

northern part of Nigeria, Plateau state. Additionally, the people are found

concentrated at the southern region of Plateau state where they are

18

surrounded by hills and beautiful vegetations. The local government area

where the people can be found is Qua’an-Pan, the nearest large towns to

them are Jos in Plateau state and Lafia in Nasarawa state.

1.3.9 Festivals

Among the Mernyang people, there are two major festivals that are

being observed. The first one comes up annually and it involves all the

speakers of Mernyang at home and abroad, far and near. This is done once

in a year usually in the first quarter of the year. During this occasion, a lot

of activities are usually lined up to inform, educate and entertain the entire

Mernyang people as well as their supporters and neighbours. This annual

festival is traditionally called ‘Pan’. It is often regarded as an event mark

the happiest or most joyous day in a year among the people. More

interestingly during this event, a lot of social dances and musical

presentations are exhibited, among which are; giyajhang feer, cheer,

koem, snal be’et, gyajeplang, gyamoefan, Doerung, gaagala etc Other folk

activities are; Nadoeng, Doet, Pagal, Shee, Koes, Fnaskop, Seegoefin,

Nawak, war etc.

19

The second festival is celebrated district by district. Each district has

its peculiar way of observing this festival. Also, a lot of activities are usually

show-cased for the education and entertainment of the audience that

grace the occasion.

1.4 SCOPE AND ORGANIZATION OF THE STUDY

This long essay aims at studying aspects of Mernyang phonology. It

will cover the general introduction to the study, the sound inventory of the

language, the phonological process and tonal features attested in the

language.

This research work is divided into five chapters. Chapter one is the general

background of the people, the status of the language and the historical

background of the people. Also, in chapter one, the socio-cultural profile of

the people and the genetic classification of the language are examined.

The chapter also gives a brief discussion of the theoretical framework to be

used in the work and explains the mode of data collection and analysis.

Chapter two discusses the sound system of the language as well as

the tonal syllable structures.

20

In chapter three, attention is focused on the phonological process

attested in the language. Chapter four addresses the tonal processes with

their distributional patterns. Chapter five summarizes the work, gives some

recommendations and concludes the study.

1.5 DATA COLLECTION

The data for the research work was collected through the help of a

language helper with the use of the Ibadan 400 basic items (word list).

Also, with the use of frame techniques. This is a template that shows

different structural positions which a word can occur. This goes beyond

looking at words in isolation. It was used to get the relevant information

that cannot be got by means of lexical items only.

The information concerning the informants in this research is given

below:

NAME:

MICHAEL DAMAN NA’ANKAM

ADDRESS:

KWA, QUA’AN-PAN LOCAL GOVERNMENT

LANGUAGES SPOKEN: MERNYANG, HAUSA, ENGLISH

RELIGION:

CHRISTIANITY

YEARS LIVED IN KWA: 20 YEARS

OCCUPATION:

CIVIL SERVANT

1.6 GENETIC CLASSIFICATION

21

Greenberg (1974: 8) explains that African languages belong to

various families, and there are four main groups namely: NigerKordofanian, Nilo-Sahara, Afro-Asiatic and Khoisan. Based on this fact,

Mernyang language is classified under Afro-Asiatic family of African

languages, specifically under the Chadic sub-phylum which extends

downward to Mernyang.

22

Afro Asiatic

Ancient Egyptian

Semitic

Berber

Chadic

North Chadic

East Chadic

West Chadic

South Chadic

Angas

Cushitic

Angas (Angas Gerka)

Angas Proper

(1)Cakfem-Mushara Jorto Kofyar Muship Mwogharul Wgas (2)Goemu Koenoem Montol Pyapun Tal

Cakfem-Mushere

Jorto

Kofyar

Bwal

Goram

Jepal Kofyar

Docmak

23

Miship

Mwaghavul

Kwalla

Mernyang

Ngas

Source: www.ethnologue.com (Accessed November, 2010).

1.7 DATA ANALYSIS

To ensure an accurate data analysis, about 125 words were

collected, 30 nouns, 15 verbs, 7 verb-noun combinations. But the last

consonant of the verb is deleted in fast speech. The other items collected

were used to identify and determine the phonological processes in the

language.

1.8 REVIEW OF THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The theoretical framework to be used for this research is generative

phonology as in Chomsky and Halle (1968).

Generative phonology constitutes part of the linguistic theory which is

called “Transformational Generative Grammar (T.G.G) formulated by

Chomsky (1957) to cater for the inadequacy observed in classical

(Taxonomic) theory of phonological description. It gives the role of how

the mind perceives sound and how the sounds are produced with the

interpretation of utterances. The goal of generative phonology is to express

the link between sound and meaning. Generative phonology accounts for

24

some language phenomenon like: Linguistic intuition, foreign accent,

speech error etc.

1.9 STRUCTURE OF GENERATIVE PHONOLOGY

“The phonological structure is an abstract phonemic representation,

which postulates the rules that are derived from various surface forms”. It

postulates the underlying form at the systematic phonemic level from

which surface alternates have systematic relationship termed linguistically

significant generalization. Hyman (1975: 80).

The structure has three basic levels which are, underlying

representation (UR), phonological rules and phonetic representation (PR)

that is;

PHONOLOGICAL REPRESENTATION (Underlying Form)

PHONOLOGICAL RULES

PHONETIC REPRESENTATION (Surface Form)

25

According to Oyebade (1998: 13) underlying representation is the nonpredictable, non rule derived part of words. It is a form with abstract

representation existing in the linguistic competence of a native speaker.

It is the basis of all utterance and it exist in the mental dictionary

representation. For instance, the different forms of negation prefix in

English like im-(possible), il-(legal), ir-(regular) having the same meaning

are phonologically accountable.

1.9.1 Phonological Representation

Generative phonology assumes 3 very crucial components. The

underlying representation, the phonetic representation and the rules which

link the two together, called the phonological rules.

These components are reviewed below;

underlying representation: Oyebade (2008: 12) assumes underlying

representation to be an abstract representation existing in the competence

of the native speaker. The underlying representation is the most basic form

of a word before any phonological rules have been applied to it. The

26

abstract representation is also known as the phonological representation

and this competence can be scientifically investigated.

1.9.2 Phonetic Representation

It is the form of a word that is spoken and heard. It is also known as

the surface level. Phonological structure reflects the linguistic competence

of the native speaker to compute a phonetic representation for the

potentially infinite number of sentences generated by the syntactic

component of the grammar.

Generative phonology seems to consider this level as being trivial and

not worth too much attention except perhaps as a source for the

verification and justification of the proposed underlying representation.

1.9.3 Phonological Rules

It maps underlying representation into phonological representations.

They delete, insert or change segments. They are said to show the

derivational sequence in its journey from the underlying level to the

phonetic level. They must be able to capture the phonological phenomenon

27

in the simplest form. There are two types of rules in phonological rules;

features changing rules and fill in rules.

Features changing rules change the features of the input to that of

the output. The other rule as name implies are rules which fill in empty

slots.

Phonological rules have to be precise in a scientific account of

linguistic phenomena. For instance, a rule can say insert a high front vowel

between cluster of consonants, and another rule says insert a high front

vowel after a word-final consonant. The rules can be formalized thus:

(a)

Ø

i/c – c

(b)

Ø

i/c - #

We observed that the two rules are identical in both input and output.

These two rules can be collapsed to become one rule which can be

represented thus;

(c)

Ø

i/c - - -

c

#

28

i.e. a high front vowel is inserted either between two consonants or after a

consonant at word final position. We also make use of notational devices in

phonological rules, which are

angled bracket notation

(< >)

alpha notation

()

brace notation

({ })

multiple variable notation

(, , v etc).

29

CHAPTER TWO

BASIC PHONOLOGICAL CONCEPTS

2.0 INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses the basic phonological concepts and

introduces the sound inventory in Mernyang language, that is, consonant

and vowels. Also showing the distribution of sounds in the language using

words in form of examples. The distinctive feature matrix of the vowel

segments are also discussed along with the justification of the feature

used. Finally, this chapter discusses the redundancies of the sound

segments – consonants and vowels in Mernyang language.

2.1 BASIC PHONOLOGICAL CONCEPTS

What is Phonology?

Phonology is a branch of linguistics which studies speech sound i.e. it

studies how sound forms systems and patterns in language (Yusuf 1992:

35). The study of phonology is based on two stages

i.

Study of sounds in a language (identification, description of

sounds in a language).

30

ii.

Part of the theory of grammar (grammar encompasses other

aspects of languages) which are syntax, semantics etc.

Based on this theoretical status, Yule, (1985) submits that phonology

is concerned with abstract or mental aspects of the sounds in language

rather than with the actual physical articulation of speech sounds.

Phonology is concerned with how these sounds are put together and

organized in a language to form meaningful words.

1.

Principle of Minimal Pair

2.

Principle of Complementary Distribution

3.

Phoneme and Allophone

2.1.1 Principle of Minimal Pair

These are pairs of words that differ in only one segment in a

language. The differing segments must be in the same position in the two

words, be different in only their values for the phonetic distinction in

question. Finally, the two must mean different things that is, they must not

simply be alternative pronunciations of the same word. Examples of

minimal pair in English language

31

bat

[bæt]

bad [bæd]

pat

[pæt]

bat

[bæt]

hat

[hæt]

hot

[ht]

2.1.2 Phonemes and Allophones

Phonemes are significant sounds that constitute change in meaning

(Hyman 1975: 4). The study of a particular language entails the knowledge

of these significant sounds. While allophones are the different realization of

a phoneme. We can test for phoneme using four principles:

A phoneme being one of the basic phonological units of which all

words in the language are composed. We represent a phoneme with a

symbol placed in slant brackets, as opposed to square brackets. The

various sounds that make up a phoneme are known as its allophones.

32

The grouping of sounds into phonemes is different in different

languages, or even in different variables within one language. Examples of

phonemes and allophones in English language.

Phonemes

Allophones

/a/

[æ : a ]

/n/

[n ŋ m]

2.1.3 Complementary Distribution

When we compare the distributions of two sounds in a language, we

may find that they are partially similar, that is, the two sounds share some

environments. For example [ph] may appear in much the same

environments as [th] in English. However, if we compare the environments

of two sounds that are allophones of the same phoneme in the language in

question we will often find they can never appear in the same

environments their distributions are completely different from one another.

This is called complementary distribution. Examples of complementary

distribution in English language;

angry

[æŋgri]

33

ambit

[æmbit]

animal

[ænIml]

king

[kiŋ]

anguish

[æŋguI]

In the above examples, we can see that the nasals occur in

complimentary distribution due to their environment of occurrence. The

change in the nasals is due to the sounds following each of the nasals. If

we are to choose one segment to be the basic of the nasals. Then /n/ will

be chosen, because /n/ can occur in any environment.

[m] before labials

/n/

[ŋ]

before velars

[n]

else where

2.2 SOUND INVENTORY

Every natural language has its own sound inventory. It has to do with

the nature of sounds in terms of segments status with phonemic segment.

34

Oyebade (1998) defined vocal sounds used in human speech and

pattern, which produce intelligent meaningful utterance sounds in a given

language can be classified into consonants and vowel. Above the segment,

we have the suprasegmental, which contains prosodic features like tones,

intonation, stress, length etc. All these suprasegmental features are above

the segments and that is why they are called the supra segments.

For instance, in a stress language, we have stress which could make

a lot of differences in words containing the same segment. For example,

the difference between the English nouns and verbs below:

Noun

Verb

‘Present

Pre’sent

‘Convert

Con’vert

‘Progress

Pro’gress

The differences between the verb-noun distinction here is the

placement of stress on the first syllable for noun, and placement of stress

on the second syllable for verbs.

35

Unlike English language, African languages operate with tone rather

than stress.

2.3. TONAL INVENTORY

Pike (1948: 93) defined a tone language as a language having

significant but contrastive pitch on each syllable.

Mernyang language attest 3 levels of tone which are high tone [/],

mid tone [-], and low tone [\]. Tone is a common features to African

languages tone brings difference in the meaning of a words just as stress

brings a change in meaning to words in English language.

2.4 SYLLABLE INVENTORY

Syllable is a smallest part of a word that can be pronounced alone. It

is a unit at a higher level than a phoneme. Syllable represents a level of

organization of the speech sounds of a particular language. We say a

particular language because languages vary in their syllable structure.

However, the most common type of syllable is CV(C) i.e. consonant

vowel (consonant).

SYLL

36

ONSET

CORE

OR

NUCLEUS

OR

CENTER

CODA

The first consonant (c) is the onset which is the beginning of the word,

vowel (v) is the core/nucleus which is the peak of the word, and the

second consonant (c) is called the coda. This is the end of a word. Vowels

usually forms the center of a syllable which is also called the nucleus. While

the onset and coda are formed by the consonant (c).

However, we should note that it is not only vowel that can serve as

the nucleus of a syllable. For example, in English and Yoruba language, we

have some syllabic consonants i.e. consonants that can constitute the

syllable peak. E.g. [m, n, l].

Also, a syllable can either be opened or observed that is we can have

an open syllable or close syllable. An open syllable ends with a vowel while

the close syllable ends with a consonant.

37

2.4.1 Syllable Structure in Mernyang

Mernyang language attest to both open and close syllable structures.

Examples of opened syllable;

[s’]

‘food’

[tì]

‘thigh’

[súãkwà]

‘maize’

[d’ba]

‘tobacco’

[iali]

‘needle’

Examples of closed syllable;

[àgàl]

‘money’

[εp]

‘axe’

[ῖŋ]

‘mortar’

[mar]

‘millet’

Here are the possible syllable structures in Mernyang language

CV

VC

CVC

38

39

2.5 SOUND DISTRIBUTION

2.5.1 Consonant Sounds

Consonant sounds are produced by obstructing the air flow totally or

partially at some point in the vocal tract. Consonant can be described using

three parameters namely.

1.

Place of articulation

2.

Manner of articulation

3.

State of the glottis (Oyebade 1998: 16).

Place of Articulation

This is the point at which articulators meet to obstruct airflow in the

course of sound production. This obstruction may occur in between two

lips, the teeth or the tongue. That is the obstruction may take place on the

lower lip and upper teeth, the tip of the tongue and the alveolar ridge, the

body of the tongue and the palate, then back of the tongue and the velum.

This include, the bilabial, alveolar, velar, palatal etc.

40

Manner of Articulation

This answers the question “HOW”. It shows how the sounds are

produced and the degree of obstruction in sound production. They include

stops, fricatives, affricates, nasals lateral roll, approximants.

State of the Glottis

This helps to indicate if the sound in question is voiced or voiceless.

Voiced sounds are sounds produced with vibration in the vocal tracts, while

voiceless sounds are sounds produced less or no vibration in the vocal

tracts. Voiced sounds are indicated as + voiced while voiceless sounds are

regarded as – voice.

41

Implosives

b

Fricatives

t d

g

Glottal

k

Labio velar

kj gj

Labialized

velar

Palatal

Palato

alveolar

Alveolar

Palatalized

alveolar

dj

Velar

P b

Palatalized

velar

Stop

Labio dental

Bilabial

Palatalized

labio-dental

2.5.2 Consonant Segments in Mernyang

Kw gw

?

d

fj

f v

s z

Affricate

h

t dз

Nasal

m

n

Lateral

l

Trill

r

ŋ

Roll

j

w

Approximant

Consonants are sounds produced with partial or total obstruction of

air in the airstream.

Mernyang language attest 31 phonemic consonants and they are

shown below:

Consonants distribution in consonants sounds are sound produced with

total or partial obstruction of air in the air stream consonant can occur at

word initial medial or final in the language. The distribution of consonants

in Mernyang language are as follows:

42

[p]: Voiceless bilabial stop

Word Initial Occurrence

[páŋ] ‘stone’

[pã]

‘rain’

[pà?àt] ‘five’

Word Medial Occurrence

[gpãŋ] ‘house’

[kwakapãŋ] ‘bark’

[dàpìt] ‘monkey’

Word Final Occurrence

[dìp] ‘hair’

[pìεp] ‘beard’

[dp] ‘penis’

[b]: Voiced bilabial stop

Word Initial

[barb] ‘arm’

[biat] ‘cloth’

[bsãŋ] ‘horse’

Word Medial

[bìubã] ‘rubbish heap’

[dakabal] ‘crab’

43

[labl] ‘bird’

Word Final

[barb] ‘arm’

[m]: Bilabial nasal

Word Initial

[mùs] ‘wine’

[mòòr] ‘oil’

[m`gór] ‘fat’

Word Medial

[nàmús] ‘cat’

[nmúat] ‘toad’

[nàmat] ‘woman’

[mat] ‘female’

Word Final

[swum] ‘name’

gzm] ‘rat’

[sgm] ‘horn’

[t]: Voiceless alveolar stop

Word Initial

[tk] ‘neck’

[tm] ‘sheep’

[tagam] ‘blood’

44

Word Medial

[amt] ‘thirst’

[kàhtεp] ‘plait’

[matgdik] ‘wife’

Word Final

[miεt] ‘enter’

[lúgút] ‘fear’

[tá?át] ‘shoot’

[d]: Voiced alveolar stop

Word Initial

[dp] ‘penis’

[dgl] ‘room’

[dgũŋ] ‘he goat’

[dagr] ‘star’

Word Medial

[dad] ‘bat’

[dεdã] ‘old person’

[matgεdik] ‘wife’

[n]: Alveolar nasal

Word Initial

[ndiejεt] ‘smoke’

[niali] ‘needle’

[ngmàm] ‘sea’

45

Word Medial

[gn`k] ‘back’

[s]: Voiceless alveolar fricative

Word Initial

[sár] ‘hand’

[s’] ‘food’

[súãkwá] ‘maize’

Word Medial

[bsãŋ] ‘horse’

[bsῖŋ] ‘house’

[mìskágám] ‘chief’

Word Final

[àgàs] ‘teeth’

‘lìís] ‘tongue’

[wus] ‘fire’

[z]: Voiced alveolar fricative

Word Initial

[zεl] ‘saliva’

[zugúm] ‘cold’

[zgp] ‘pound’

Word Medial

[mzp] ‘guest’

[dijgazŋ] ‘urinate’

46

[l]: Alveolar lateral

Word Initial

[lgũ] ‘dry season’

[lúwa] ‘meat’

[lεmú] ‘orange’

Word Medial

[dílãŋ] ‘swallow’

[flak] ‘heart’

[nlk] ‘thorn’

Word Final

[dbεl] ‘lizard’

[dàkabál] ‘crab’

[pgvól] ‘seven’

[r]: Voiced alveolar trill

Word Medial

[mrbãŋ] oil palm’

[tarpas] ‘kite’

[jagurum] ‘twenty’

Word Final

[nεr] ‘vagina’

[nar] ‘skin’

[mar] ‘millet’

47

[]:Voiceless palato alveolar fricative

Word Initial

[àgàl] ‘money’

[ar] ‘friend’

[àp] ‘divide’

Word Medial

[iik] ‘body’

[ndkgak] ‘gather’

[t]: Voiceless palato alveolar affricate

Word Initial

[tugn] ‘nail’

[tì] ‘thigh’

[tàgàm] ‘guinea fork’

Word Medial

[ntugur] ‘duck’

[nàkùptís] ‘snail’

[j]: Voiced palatal approximant

Word Initial

[jugur] ‘breast’

[jagurum] ‘twenty’

[jŋpεh] ‘call’

Word Medial

[ndiejεl] ‘smoke’

48

[gjíl] ‘earth’

[díéjél] ‘war’

[kj]: Voiceless palatalized velar stop

Word Initial

[kjãŋ] ‘hoe’

[gj]: Voiced palatalized velar stop

Word Initial

[gjara] ‘hawk’

[gjaiá] ‘dance’

[k]: Voiceless velar stop

Word Initial

[ka?ah] ‘head’

[kúm] ‘navel’

[kugur] ‘charcoal’

Word Medial

[nàkùptís] ‘snail’

[tεkah] ‘fetish’

[jàkgs] ‘run’

Word Final

[kwak] ‘leg’

[ìsik] ‘body’

[t?k] ‘soup’

49

[g]: Voiced velar stop

Word Initial

[gŋ] ‘nose’

[gk] ‘back’

[gòrh] ‘kolanut’

Word Medial

[jakgso] ‘run’

[vúgúm] ‘hat’

[àgàl] ‘money’

Word Final

[kmt’g] ‘leaf’

[buúgàtg] ‘tie rope’

[ŋ]: Velar nasal

Word Initial

[ŋkia] ‘vulture’

Word Medial

[jŋpεh] ‘call’

[nãŋmbi] ‘ask’

[tàŋkp] ‘like’

Word Final

[gãŋ] ‘mat’

[tεŋ] ‘rope’

[dзáŋ] ‘calabash’

50

[fj]: Voiceless palatalized labio dental fricative

Word Initial

[fju] ‘cotton’

[dj]: Voiced palatalized alveolar stop

Word Initial

[djip] ‘feather’

[djidr] ‘remember’

Word Medial

[ndjik] ‘build’

[peidje] ‘dawn’

[f]: Voiceless labio dental fricative

Word Initial

[fù?uh] ‘mouth’

[flak] ‘heart’

[fu?usbã] ‘sunshine’

Word Medial

[gfur] ‘town’

[lfú] ‘word’

[ùf] ‘new’

[v]: Voiced labio dental fricative

Word Initial

[vúgúm] ‘hat’

[vl] ‘two’

51

[vàŋ] ‘wash’

Word Medial

[pgvl] ‘seven’

[b]: Voiced bilabial implosive

Word Initial

[bat] ‘belly’

[blãŋ] ‘work’

[ba?ãŋ] ‘red’

Word Medial

[dgbt] ‘stomach’

[dbεl] ‘lizard’

[d]: Voiced alveolar implosives

Word Initial

[dŋ] ‘well’

[dз]: Alveolar affricate

Word Initial

[dзagam] ‘jaw’

[dзm] ‘matchet’

[dзεp] ‘children’

[]: Voiced palato alveolar roll

Word Medial

[w’’] ‘arrive’

52

Word Final

[á] ‘road’

[sa] ‘ten’

[mg] ‘fat’

[kw]: Voiceless labialized velar stop

Word Initial

[Kwak]

[kwakaptŋ] ‘bark’

Word Medial

[suãkwa] ‘maize’

[gw]: Voiced labialized velar stop

Word Initial

[gwui]’donkey’

[w]: Voiced labio velar approximant

Word Initial

[wàk] ‘seed’

[war] ‘road’

[wãŋ] ‘village’

Word Medial

[bãgwus] ‘hot’

[áwúbã] ‘bad’

[tugulwã] ‘mould’

53

[?]:Voiceless glottal stop

Word Initial

[pa?at] ‘five’

[ka?ah] ‘head’

[sε?εh] ‘song’

[h]: Voiceless glottal fricative

Word Initial

[kahtεp] ‘plait’

Word Medial

[rógòh] ‘cassava’

[górh] ‘kolanut’

[te?eh] ‘story’

2.5.3 Vowels in Mernyang Language

Vowels are sounds produced with partial or no obstruction of air in

the air stream. There are 10 vowels attested in Mernyang language. We

have 8 short vowels and 2 long vowels in the language. The short vowels

are; /i, ε, e, ,o,a, , u/ while the long vowels are /ε:, u:/. These sounds

can be properly shown in the vowel chart below.

Front

Central

Back

u:

Mid high i

54

u

Mid low

e:

Low

e

ε

o

a

2.5.4 Distribution of Vowels

Vowels can occur at word initial, word medial or word final position in

Mernyang language. The distributions are as follows:

[i]: High front unrounded vowel

Word Medial

[ῖŋ] ‘mortar’

[kàmbìl] ‘basket’

[dil] ‘ground’

Word Final

[tím] ‘day’

[fìí] ‘dry’

[wágjì] ‘come’

55

[e]: Front mid-high unrounded

Word Medial

[fiew] ‘spin’

[ep] ‘firewood’

[piep] ‘wind’

Word Final

[ndèmãndé] ‘suprass’

[peslje] ‘dawn’

[e:]: Front mid high unrounded long vowel

Word Medial

[pe:dje] ‘dawn’

[ε]: Front low unrounded vowel

Word Initial

[εs] ‘bone’

[εs] ‘feaces’

Word Medial

[dзεm] ‘matchet’

[gdεt] ‘soon’

[dbεl] ‘lizard’

Word Final

[íε] ‘learn’

[àgàspε] ‘abase’

56

[]:Central Mid-low unrounded vowel

Word Initial

[k] ‘goat’

Word Medial

[lahkn] ‘say’

[kmtg] ‘leaf’

[nlk] ‘thorn’

Word Final

[war’] ‘arrive’

[jàkg’s] ‘run’

[lahkn] ‘say’

[u:]: Back high rounded vowel

Word Initial

[ùfó] ‘new’

Word Medial

[kúm] ‘navel’

[mùs] ‘wine’

[lúwa] ‘meat’

Word Final

[lì?ú] ‘snow’

[lau] ‘bag’

[lòfù] ‘word’

57

[o]: Back mid-low rounded vowel

Word Initial

[Tógòh] ‘cassava’

[górh] ‘kolanut’

[dàgó] ‘man’

Word Medial

[mùgó] ‘person’

[ùfó] ‘new’

[]:Back low rounded vowel

Word Initial

[rũŋ] ‘dust’

Word Medial

[km] ‘ear’

[gnk] ‘back’

[mrbãŋ] ‘oil palm’

[a]: Back low unrounded vowel

Word Initial

[ajit] ‘eye’

[àgàs] ‘teeth’

[àás] ‘egg’

Word Medial

[nàr] ‘skin’

[wál] ‘weep’

58

[katεp] ‘plant’

Word Final

[là] ‘son’

[súá] ‘drink’

ta?á] ‘blow’

2.5.5 Vowel Nasals

Mernyang language attests nasal vowels. These nasal vowels can

occur at word medial or word final position. But the long vowels in

Mernyang language does not have nasal counterpart. The nasal vowels

are;

[ῖ]:- [pãfῖ]

[ῖŋ]

‘grinding stone’

‘mortal’

[ề]:- [jagalgtềŋ]

‘fly’

[]:- [tŋ]

‘grass’

[bsŋ]

‘horse’

[ồ]:- [jabutồŋ]

‘lie(down)’

[]:- [gŋ]

‘nose’

[wuj]

‘senior’

59

[ã]:- [suãkwa]

‘maize’

[kjãŋ]

‘hoe’

[fu?usbã]

‘hoe’

[ε]:- [tεŋ]

[tεkah]

‘rope’

‘fetish’

These are nasalized vowels in Mernyang language. They include [ã, ề, ε, ῖ,

ồ, , ũ, ].

60

Front

Central

Back

Mid high ῖ

Mid low

ũ

ề

ồ

ε

Low

2.5.6

ã

Distinctive

Feature

Matrix

for

Mernyang

Language

Consonants

Distinctive features are all… set of articulation and acoustic feature

sufficient to distinguish one from other, the great majority of the speech

sounds used in the languages of the world (Halle and Clements 1983: 6)

These features are smallest element in phonological analysis and they are

universal. The feature must have functional relevance in the language.

Such features are significant and explicit in the pattern of speech. It is

assumed that a feature is either present or absent in a speech sound by

the principle (+ or -). The relevance of these features is shown when it is

61

applied to redundancy principle. The table below shows the distinctive

feature matrix for Mernyang language.

62

p

b

b

m

fj

f

v

dj

t

d

d

s

z

n

l

r

t

dз

j

kj

gj

k

g

ŋ

kw

gw

w

?

h

+ CONS

+ + + +

+ + + +

+ + + + + + + + + + +

+ + +

+

+ + + + +

+

+

+ +

+ SON

-

-

-

+

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ + + -

-

-

+ + -

-

-

-

+ + -

-

+

-

-

+ SYLL

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ COR

-

-

-

-

+ + + +

+ + + + + + + + + + +

+ + -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ ANT

+ + + +

-

+ + -

+ + + + + + + + -

-

-

+ -

-

-

-

-

-

-

+

+

+

-

-

+ LAB

+ + + +

-

+ + -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+

-

-

+ CONT

-

-

-

-

+ + + -

-

-

-

+ + -

-

-

+ -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ -

-

-

-

-

+

+ NAS

-

-

-

+

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ -

-

-

-

-

+ STRD

-

-

-

-

-

+ + -

-

-

-

+ + -

-

+ + +

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ -

-

-

-

+

+ VOICED

-

+ + +

-

-

+ +

-

+ + -

+ + + + -

-

+ + -

+

-

+ + + -

+

+

-

-

+ DELREL

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ +

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

63

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

2.5.7 Justification of the Features Used

Distinctive features are used in classifying segments into their natural

classes. There is no occurrence of the sound have exactly the same feature

through matrix and phonological rules (Halle 1983: 6). The features are

described below;

i.

[+cons]: Consonants are sounds produced with partial or total

obstruction of air along the vocal tract. Non-consonant are

produced without any obstruction of air in the air stream.

ii.

[+ Son]: These are sounds produced when in addition to the

blockage of air in the month the air continues to resonate and

then move through the nose). Because the air passes through the

nose, it does not mean the velum is lowered. The air pressure

inside and outside the mouth is approximately the same. Sounds

produced with this feature are, glides, nasals, liquids and vowels.

iii.

[+ Syll]: These are sounds which constitutes the syllable peak.

Example of such words are vowels and syllabic consonant.

iv.

[+ Cor]: They are sounds produced with the blade of the tongue

rising towards or touching the hard palate or the teeth. Examples

of such sounds are alveolars, palato-alveolars, palatals, dentals.

v.

[+ Ant]: They are produced at the front or anterior region of the

mouth. Examples of such sounds are, labials, alveolars, dentals.

vi.

[+ Labial]: These are sounds produced with protrution of the lips

that is sounds produced with the involvement of the lips.

Examples of these sounds are labial consonant and rounded

vowel.

vii.

[+ Nasal]: These are sounds produced with the lowering of the

velum in which the air passes through the nasal cavity. Examples

are nasalized vowels and nasals.

viii.

[+ Cont]: They are sounds that causes friction. In their

production, the air is not completely stopped in it passage through

the oral cavity. Fricatives are classified under this feature.

ix.

[+ Strident]: These are sounds produced with an obstruction

that makes the air stream strike two surface by producing high

lxv

intensive fricative noise. [+ trident] are fricatives, affricates, labio

dentals.

x.

[+ Voiced]: They are sounds produced with the vocal coral

vibrating. Voiced consonants and vowels are categorized as [+

voiced].

xi.

[+ Delrel]: Are produced with sharp stop but fricative release.

We have affricates in the category of these feature.

2.5.8 Segment Redundancy for Consonants

Redundancy is the principle that helps in predicting some feature

from the presence of other feature, feature that predicts the feature of the

other is said to be redundant. (Hyman 1975: 42).

In Mernyang language, a number of feature that are completely

predictable at all stages of derivation is attested. The output of

phonological components must specify all feature in such a way that it

indicates necessary feature used in derivation. All features that are

redundant are expressed as fill-in-rule or [if, then].

i)

if

[+nas]

lxvi

then

ii)

if

-Cont

-Strid

+Voice

+Son

[+ syll]

then

iii)

if

+Son

- Cons

[+ ant]

then

iv)

if

then

[+ cons]

[+ Cons]

+Voiced

-Strid

lxvii

v)

if

[-Cons]

then

+ Son

- ant

- lab

- nas

+ cont

+ voiced

+ strid

2.5.9 Distinctive Features Matrix for Vowels

I

e:

e

ε

u:

u

o

a

+ Syll

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+ High

+

-

-

-

-

+

+

-

-

-

+ Low

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+

+ Back

-

-

-

-

-

+

+

+

+

+

+ Round

-

-

-

-

-

+

+

+

+

-

+ ATR

+

-

+

-

-

-

+

+

-

-

2.5.10 Justification of Features Used

1.

[+ Syll]: They are sounds produced without any form of

obstruction and they constitute peak of syllables. This includes all

vowels.

lxviii

2.

[+ High]: These are sounds produced by raising the body of the

tongue towards the hard palate. For example [i, u:, u].

3.

[+ Low]: They are sounds produced by drawing the root of the

tongue downward from the mouth. E.g.[a]

4.

[+ Round]: They are vowels produced with the rounding of the

lips. For example [u:, u, o, ].

5.

[+ Back]: Are vowels produced with body of the tongue relatively

retracted e.g. [u:, u, o, , a].

6.

[+ ATR]: It involves drawing the root of the tongue forward,

enlarging the pharyngeal cavity and often raising the body of the

tongue as well. E.g. [i, e, u, o].

2.5.11 Segment Redundancy for Mernyang Vowel

1.

if

then

[+ high]

[- low]

lxix

2.

if

[+ low]

then

+back

-high

-round

3.

4.

if

[-back]

then

[- round]

if

[+ round]

then

+ back

- low

lxx

CHAPTER THREE

PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES

3.0 INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, the phonological processes discovered in Mernyang

language are discussed below, they are; assimilation, palatalization,

labialization, nasalization, deletion, insertion.

3.1 PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES

Phonological processes are sound modifications motivated by the

need to maintain euphony in a language or to rectify violations of wellformedness constraints in the production of an utterance (Oyebade, 2008:

61) quite often when morphemes are joined together (syntactic

collocations), these constraints are violated. These violations are repaired

so to speak by some mechanisms know as phonological processes.

Oyebade 2004: 61.

Phonological processes came about as the need to maintain the

musical quality of the utterance and to make its production easy or

economical to release the circulatory contact for contiguous sounds. This

lxxi

effect is reduced if both contiguous sounds require the same articulatory

mechanism production.

The phonological processes attested in Mernyang language shall be

examined in this chapter.

3.1.1 Assimilation

Oyebade [1998 61] refers to assimilation as a process

contiguous segments influence each other by becoming

Assimilation takes place when two contiguous

whereby

more alike.

segments influence each

other by becoming more alike or identical in all or some of the features of

their production.

Vowel – Vowel Assimilation

Assimilation in mernyang language can occur between vowels.

Che’etse + ayaba

Cooking

banana

tʃe’etsaajaba

cooked banana

Wupíá + e’es

wupíe’es

white

white bone

bone

lxxii

awúba + orim

awúboorim

bad

bad beans

beans

toe

+ ass

taass

kill

+ dog

kill dog

From the example shown above, the vowel – vowel

assimilation

process is found in mernyang language when a verb and a noun or an

adjective and a noun collocate.

There is assimilation across morpheme boundary, the final vowel of

the adjective or verb is lost and assimilates the initial vowel of the noun or

the initial of the noun is lost and assimilates

adjective or verb.

The vowel assimilation rule is given below;

lxxiii

the final vowel of the

V1

V2/V1 # V2

+syl.

+syl.

+syl.

-cons.

-cons.

-cons.

1

#

+syl.

2

-cons.

3.1.2 Labialisation

According to Oyebade (2008: 66), labialization is the super-imposition

of liprounding on a segment in such a way that the feature of a vowel now

attaches to the consonant articulated. Examples of these sounds in

Mernyang language are;

Kwák

[kʷák]

‘leg’

Súákwá

[súákʷá]

‘maize’

Kwút

[kʷút]

‘leopard’

Kwàt

[kʷàt]

‘pay [for something]

The rule to account for labialization in Mernyang language is given below;

-son.

+lab.

+syll.

-cont.

+rnd.

A stop becomes labialized when it occurs before a rounded vowel.

lxxiv

3.1.3 Palatalisation

This is the super-imposition of tongue raising on a segment

(Oyebade, 2009: 65). In the articulation of some consonants, it is observed

that we experience the articipatory fronting of the tongue while tongue is

raised towards the roof of the mouth, taking a position in articulating the

high front unrounded vowel [i]. Here are examples in Mernyang language:

Peedye

[pe;dje]

‘dawn’

Dyíp

[djíp]

‘feather’

Ndyík

[ndjík]

build[house]’

Dyidoer

[djídər]

‘remember’

The rule to account for palatalization in Mernyang language is given thus;

lxxv

+cons.

+high

+syll.

-syll.

+high.

-rnd.

A consonant becomes palatalized when it occurs before a front vowel.

3.1.4 Nasalisation

Crystal (1991) describes nasalization as a process whereby an oral

segment

acquires

nasality

from

the

neighboring

nasal

segment.

Nasalization is the superimposition of nasal features on a neighboring

segment. It is a situation whereby a vowel assimilate consonant feature

(vowel consonant assimilation) (Oyebade, 2008: 66). Examples of

Mernyang language are:

pangfin

+

grinding stone

ufó

new

paŋfĩnũfó

‘new grinding stone’

pan +

íló

rain

heavy

‘heavy rain’

noegoen

+

ùre’ét

ngnũr?t

good

‘good mother’

mother

pãnĩl

+ syll

+cons

lxxvi

- cons

[nas]

+ nas

_____

- nas

3.1.5 Insertion

Insertion is a process which occurs when an extraneous element not

present originally is introduced into the utterance usually to break

unwanted sequence (Oyebade 1998: 74) Mernyang attests to morphemic

insertion.

i.

ii.

iii.

iv.

sàr

gom

sar

ka

ten

one

ten

plus one

sàr

val

sar

ka

ten

one

ten

plus two

‘twelve’

sàr

kũn

sar

ka

sarakũn

ten

three

ten

plus three

sàr

fr

sar

ka

ten

four

ten

plus four

gom

vl

‘eleven’

kũn

fr

sarkagom

sarakvl

‘thirteen’

sarkafr

‘fourteen’

The morpheme [ká] is inserted between two words at morpheme

boundary.

lxxvii

3.1.6 Deletion

Deletion is another common process in languages. It involves the loss

of a segment under some language – specifically imposed conditions.

Deletion could involve vowels or consonants. (Oyebade 2008: 69).

Mernyang language attests to consonant deletion process. Examples are;

at

+

wòe

awòe

bite

snake

‘snake bite’

dàkùl +

làlà

live

child

‘left the child’

shay +

long

shalong

friend

king

‘friend of a king’

wus +

yàbà

wuyàbà

hot

banana

‘hot banana’

dakulàlà

In the examples above, the first of the two consonants at morpheme

boundary is deleted. This is because, the language does not permit

consonant cluster at morpheme boundary.

lxxviii

C

+ cons

Ø/____ + C

ø/ ____ + + cons

- syll

- syll

3.1.7 Vowel Elision

According to Oyebade (2008: 69), vowels are usually deleted when

two or more vowels occur across morpheme boundary. When such an

occurrence is introduced by morphological processes, the language may

choose to drop the first or the second of the contiguous vowels.

But Mernyang language does not attest to this phonological process.

In the language, vowels do not delete at morpheme boundary. We have

example of vowels not deleted:

luwa

+

meat

dàgó

eat

goat

+

man

s

k

áwúbàn

‘goat meat’

bad

+

εss

bone

luwak

dagoawaban

‘bad man’

sεss

‘eat the bone’

lxxix

ajaba

+

plantain

aw

urε?ε?εt

good

+

moon

ùfó

‘good plantain’

new

ua

+

drink

urɔk

+

tobacco

ε?εs

grind

[awùfó/

‘new moon’

tasty

dba

/ajabaurε?εt/

/uaurɔk/

‘tasty drink’

/dbaε?εs/

‘grinded tobacco’

The only instance where we have vowel deletion in the language is

when we have two vowels at morpheme boundary, i.e. V1 and V2 due to

the tone one of the vowels is carrying one of the vowel will be deleted. For

instance if we have

lxxx

H

pem

+

six

L

H

k

pemk

goat

‘six goats’

L

H

H

bàù +

úrε?εt

báúrε?εt

bow

good

aw +

ba

moon

full

M

L

L

ùfó

laùfo

lau

+

‘good bow’

awba

‘full moon’

bag

new

‘new bag’

L

M

L

dbà +

awban

dbàwban

tobacco

bad

ajabà +

awbán

plantain

bad

‘bad tobacco’

ajabàwban

‘bad plantain’

lxxxi

M

H

H

luwa +

áwúbàn

luwáwban

meat

bad

H

M

H

dàgó +

odɔk

dagódɔk

man

short

suá

+

awban

‘bad meat’

‘short man’

guinea corn bad

suáwban

‘bad guineacorn’

In the above data, when a low tone (\) and mid tone (-) follow each

other at morpheme boundary the mid tone is deleted.

When the high tone (/) and mid tone (-) follow each other at

morpheme boundary the mid tone is deleted.

When the low tone (\) and high tone (/) follow each other at

morpheme boundary, the low tone is deleted irrespective of which of tone

comes first. These lead to the issue of tone hierarchy i.e. the tones are

arranged hierarchically.

lxxxii

H

L

M

High

Low

Mid

Rule 1:

+ syll

- cons

+ syll

- cons

-HT

Rule 2:

+ HT

+ syll

- cons

-HT

+ syll

- cons

+ HT

lxxxiii

CHAPTER FOUR

TONE AND SYLLABLE PROCESSES IN MERNYANG LANGUAGE

4.0 INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses the features of tones in Mernyang language,

tone typologies, the co-occurrence of tones in Mernyang language. The

chapter also examines the functions of tones in Mernyang language. Finally

it discusses the syllable structure and syllable process of the language.

4.1 WHAT IS A TONE LANGUAGE?

Tone languages are languages that have “…lexically significant,

contrastive but relative pitch on each syllable” (Pike 1948: 3). Tone as a

prosodic feature has been defined and justified by linguists to be

undergoing

modifications

before

reaching

its

actual

phonetic

manifestations.

The underlying process in mechanisms responsible for this in tonal

language is referred to as tonal processes (Hyman 1975: 22).

lxxxiv

4.2 TONE TYPOLOGIES

Basically, we have two types of tone typologies and these are:

registered and contour tones. Registered tones are tones that are uniform

and discrete while the contour tones are the tones that are not stable but

rather undulating inform of waves [] (Goldsmith 1976). Registered

tone consist of levels of tones, high tone marked with an acute sign [/] mid

tone marked by a macron [-] or unmarked and low tone marked by a grave

sign [\]. The contour tones glide from one land to another level and they

are;

i.

Rising Tone: it is marked with the combination of low tone and

high tone [v] on a segment

ii.

Falling Tone: It is the combination of high tone followed

immediately by low tone on a segment. It is marked thus: [^].

4.3 TONAL PATTERNS IN MERNYANG LANGUAGE

Mernyang language attests to registered tone. This include a high

tone marked with acute accent [/], a low tone marked with a grave accent

[\] and mid tone which is represented as [-] or unmarked.

lxxxv

The tone chart of Mernyang language tones:

High tone

[/]

Low tone

[\]

Mid tone

[-]

Below are the distributions of the three tones attested in Mernyang.

High tone [/]

[wál]

‘weep’

[kút]

‘cool’

[túŋ]

‘fry’

[bát]

‘belly’ (external)

[kúm]

‘navel’

[sáY]

‘hand’

[sá]

‘food’

Low tone [\]

[pàs]

‘rainy season’

[wà]

‘snake’

lxxxvi

[là]

‘son’

[nàr]

‘skin’ (flay)

[nàs]

‘beat’ (person)

Mid tone [-]

[muar]

‘swell’

[piãn]

‘break’

[ap]

‘split’

[gãn]

‘chin’

[jugur]

‘breast’ (female)

[im]

‘yam’

[wus]

‘fire’

[kam]

‘stick’

lxxxvii

4.3.1 Co-Occurrence of Tones in Mernyang Language

This is a situation whereby tones can occur together in a word. For

example Mernyang language high tone can co-occur with high one.

[báú]

‘bow’

[sámtás]

‘cloth’

[vúgúm]

‘hat’

[básáŋ]

‘horse’

[básíŋ]

‘house’

We also have high tone co-occurring with low tones e.g.

[rógòh]

‘cassava’

[góròh]

‘kolanut’

High tone can co-occur with mid tone

[dílaŋ]

‘swallow’

[láni]

‘small’

Mid tone can co-occur with mid tone

lxxxviii

[jŋpεh]

‘call’ (Summon)

[zgp]

‘pound’

[tapãn]

‘burn’

[vaŋik]

‘was’

[nasbaŋ]

‘beat’ (drum)

Mid tone can also co-occur with high tone

[pemá]

‘six’

[ka?áh]

‘head’

Low tone can co-occur with high tone

[màgár]

‘fat’

[ìtáh]

‘pepper’

[lεmú]

‘orange’

Low tone can co-occur with low tone

[jàbà]

‘banana’

[wààk]

‘seed’

lxxxix

[kàmbìl]

‘basket’

Low tone can co-occur with mid tone

[wùjn]

‘senior/older’

[làrεp]

‘daughter’

[nàmat]

‘woman’

[màmat]

‘female’

[màmis]

‘male’

4.3.2 Functions of Tones

Tones perform different functions in a language, there functions are

lexical, phonemic also syntactic functions. In Mernyang language, tone

perform phonemic function i.e. tones are used to differentiate words which

have the same segment or that are similar, for examples;

1.

2.

[km]

‘groundnut’

[km]

‘ear’

[εss]

‘sand’

[εss]

‘bone’

xc

3.

[mùãn]

‘walk’

[múãn]

‘go’

4.4 TONAL PROCESSES

Tone processes are different modifications that tones had undergone

before reaching its actual phonetic manifestation. This underlying process

or build-in mechanism responsible in tone languages is referred to as tone

processes (Hyman 1975: 22). Also tone processes has to do with the

influence of tone on each other or the modification of tone brought about

by their interaction and relationship with segment. Schane (1973: 215).

Mernyang language attest to one tonal process.

4.4.1 Tone Hierarchy

This is a system in which the tones are arranged according to their

importance. In Mernyang language, tones are arranged hierarchically.

When there are two same vowels following each other at morpheme

boundary, one is deleted for the other based on the tone it carries.

1.

/àjàbà/

plantain

+

/awbãn/

bad

/àjàbàwbãn/

‘bad plantain’

xci

2.

/pem/

+

six

3.

4.

5.

/k/

goat

/báú/ +

/ùr?t/

bow

good

/lau/ +

/ùfó/

bag

new

/ŋkiá/

+

vulture

/pemk/

‘six goats’

/báúr?t/

‘good bow’

/laùfó/

‘new bag’

/àás/

egg

/ŋkiáás/

‘vulture egg’

In the above examples, when a low tone (\) and mid tone (-) follows

each other at morpheme boundary the mid tone is deleted as indicated in

example (i) above.

When the high tone (/) and mid tone (-) follows each other at

morpheme boundary the mid tone is deleted, as indicated in example (ii)

above.

When the low tone (\) and high tone (/) follows each other at

morpheme boundary, the low tone is deleted as shown in example (v)

above.

xcii

4.5 SYLLABLE STRUCTURE

Hyman (1975: 189) maintains that a syllable consists of the peak of

prominence in a word which is associated with occurrence of one vowel or

a syllabic consonant that represented the most primitive in all languages.

A syllable consists of phonological units and it consists of three

phonetic parts which are:

i.

The onset

ii.

Peak or nucleus

iii.

Coda

Onset is usually at the beginning of a syllable, the peak is the nucleous

while coda is the closing segment. In auto segmental phonology of J.

Goldsmith (1976), a syllable is divided into two:

i.

Onset: syllable initial segment

ii.

Rhyme: broken down into a compulsory nucleus and on optional

coda. This can be represented thus;

Syllable

xciii

Onset

Rhyme

Peak

Coda

e.g. in Mernyang language

[mar]

‘millet’

we have

xciv

Onset

Nucleus

Coda

C

V

C

m

a

r

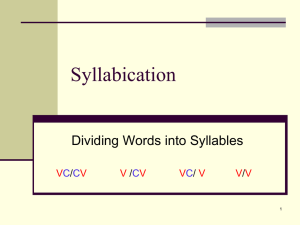

4.5.1 Types of Syllable

Syllable types is language specific. A language may exhibit either

open or closed syllable and also some languages make use of the two

(open and closed syllable).

Open Syllable

An open syllable is a syllable typology in which words ends in vowels.

In such languages, there is no form of consonant ending. It is one of the

features peculiar to African languages Whelmers (1974). Mernyang

language attests to open syllable structure. Examples are:

[sá]

‘food’

[dába]

‘tobacco’

[niali]

‘needle’

xcv

Closed Syllable

This is a syllable type which ends with a consonant. Mernyang

language also attests to the closed syllable structure. Examples are:

[àgàl]

‘money’

[sεp]

‘axe’

[im]

‘yam’

Mernyang language makes use of the two syllable typology.

4.5.2 Syllable Structure Rule in Mernyang Language

This is the rule that states the possible sequence of sounds or

segments in a syllable. Four major syllable structure. They are N, CV, VCC,

CCV and CVC.

N:

This is a syllabic nasal that usually occurs at initial position. For

examples:

[Ndùŋ]

‘that’

[ndiejεl]

‘smoke’

[ntugur]

‘duck’

[ŋkía]

‘vulture’

xcvi

CV: This is the sequence of consonant and vowel. Examples are:

[wá]

‘snake’

[là]

‘son’

[sá]

‘food’

VC:

This is the sequence of vowel and consonant. Examples are:

[k] ‘goat’

[εs] ‘sand’

[am] ‘water’

[as] ‘dog’

CVC: This is a syllable that begins with consonants followed by a vowel

then by consonant. Examples are;

[nar] ‘skin’

[sáh] ‘eat’

[wat] ‘thief’

There are also different types of syllable sequence in Mernyang

language. They are monosyllabic, di-syllabic, tri-syllabic.

xcvii

Monosyllabic:

These are words pronounced on a breath. Examples are;

[tcp] ‘tear’

[k] ‘goat’

[εs] ‘sand’

[wút] ‘untie’

Di-Syllabic

Di-syllabic words are words that are pronounced in two breaths. For

example:

[jagám]

‘jaw’

[tákát]

‘pull’

[búgàt]

‘tie rope’

[yugur]

‘breast’

Tri-Syllabic

These are words that are pronounced in three breaths.

[nákùpdús]

‘snail’

[baldgl]

‘hard’

xcviii

[matdзàdik]

‘wife’

4.6 SYLLABLE PROCESSES

Refers to the process which takes place in realization of some

syllables in a language.

4.6.1 Types of Syllable Processes

Reduplication

It is a morphological process by which all or part of a form is copied

to form another word. Reduplication is of two types, partial or total.

Partial reduplication is the most common in Mernyang language. in

the examples below a verb is reduplicated to form an adverb.

ízí

‘now’

miang

‘cloud’

ufo

‘new’

diang

‘quick’

ízí

now

miang

cloud

ufo

new

diang

quick

+

+

+

+

xcix

ízí

now

miang

cloud

ufo

new

diang

quick

izizi

‘immediately’

miangiang

‘cloudy’

ufofo

‘newly’

diangiang

‘quickly’

CHAPTER FIVE

SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5.0 INTRODUCTION

This long essay has made efforts to describe the phonology of

Mernyang language. It is observed that at it is for other languages, so it is

for Mernyang language. Words are not just string together randomly, or

arbitrary, they are well patterned and followed the principles of well

formedness.

The data used for his research work was collected through the use of

Ibadan four hundred wordlist. Meanwhile, the informant method was used

in elicitation of the data. This is because, words are not to be dealt with in

isolation.

Chapter one introduced the historical background and the people of

Mernyang. It also discussed the geographical location of the people The

major occupation of the Mernyang people is farming. They also engage in

trading activities. Majority of the Mernyang people are Christians as a result

of missionary activities which gained ground in the area. Also in this

c

chapter we discovered that Mernyang language belong to the NigerKordofanian language family.

Chapter two examined the basic phonological concepts such as

minimal pair, allophones and phonemes. Also, sound distribution and

distinctive features of Mernyang language were discussed. Mernyang

language attests to 32 consonants, 8 short vowels, 2 long vowels.

Chapter three discusses the phonological processes attested in

Mernyang language. Processes like assimilation palatalization, labialization,

nasalization insertion and deletion in Mernyang language are explained.

The fourth chapter discusses the tonal and syllable processes in

Mernyang language. The language make use of the registered tone levels;

high, mid and low tone. These tones also co-occur with each other. Syllable

structures like, N, CV, CVC, are shown in this chapter.

Chapter five which is the final chapter, summarizes the research work

and gives recommendation and the conclusion as well.

ci

5.1 FINDINGS/OBSERVATION

Mernyang language unlike majority of African languages do not attest

to vowel harmony. There is no harmony among the vowels in Mernyang

language.

It is also observed that Mernyang language make use of both the

open and closed syllable which is not a common features to majority of

African languages. The language also to attests to tone hierarchy as a

tonal process.

5.2 RECOMMENDATIONS

Through this research, useful insight has been drawn from the

structure of Mernyang phonology. As a matter of fact, the language has

not been exposed to thorough linguistic scrutiny. There is need for linguists

to focus more attention on the language. This research work has only

studied an integral part of the various fields of linguistics. Only some

aspect of phonology has been explored in this research. We hereby

recommend that linguist should focus more on other aspects of the

language.

cii

5.3 CONCLUSION

So far, this project has been able, within the scope of the work

examine the structure of the Mernyang phonology. W cannot assume that

this research work is exhaustive enough.

However, it is believed that it can serve as a reference or a source of

data for further research in Mernyang language. The various discussions

will be very useful for all students of linguistics and learners of the

language.

ciii

REFERENCES

Chomsky, N. and Halle, M. (1968). The Sound Pattern of English.

New

York: Haper and Row.

Fromkin, V. R. (ed.) (1978). A Linguistics Survey. New York:

Academic

Press Incorporated.

Goldsmith, J. (1976). Auto Segmental Phonology MIT Dissertation

IVLC.

New York: Grandland Press.

Gordon, R. G. (ed.) (2005). Ethnologic Languages of the World,

(Fifteenth Edition) Dalas Tex: SIL International.

Greenberg, J. (1974). The Languages of Africa. Bloomigton: Indiana

University.

Halle, M. and Clement, G. N. (1983). Problem Book in Phonology.