evaluation of the 2015 rheumatic fever awareness campaign

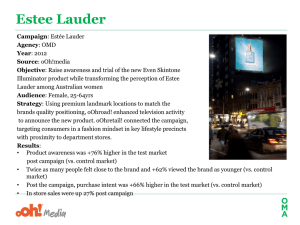

advertisement