Legislation on involuntary placement and involuntary treatment (civil

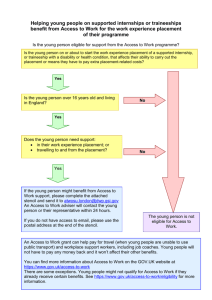

advertisement