File

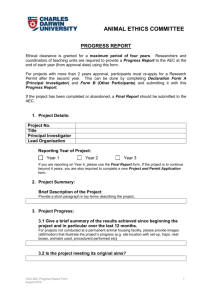

advertisement

In response to the inquiry: “how the welfare of animals used in experiments is actually monitored once an experiment is started” I would offer the following explanation: John Schofield <johnawo@xtra.co.nz> 1. It is standard practice for Animal Ethics Committees (AEC) to ask the Principal Investigator (PI); an international term for the chief scientist of the research project, to provide written details of how animals used for research, will be monitored during the study. Such details are generally included and form part of the AEC application process. For example; how often will animals be observed after the administration of drug X or surgical procedure Y? Will they be examined once, twice daily or more often than that? How often will they be weighed? Weight loss is a useful indicator of wellbeing. What signs of pain and distress will be used to determine wellbeing? These signs are very well documented for rats and mice, but they are subtle and the personnel responsible for monitoring animals need to be trained observers. Hence another common AEC question of the PI is: “precisely who will perform the monitoring and what is their training which qualifies them to undertake this?” 2. In NZ the welfare monitoring system is based on trust. The AEC trusts the PI and their staff that they will in fact, monitor welfare exactly as detailed in the AEC application. The PI trusts their graduate students to perform monitoring as agreed. And in my experience, for the most part, this trust is well placed. 3. Another AEC strategy is to require the PI to report any adverse events the animals on study might experience. And when such reports are received, a veterinarian is quickly involved to make physical examinations, diagnose problems, arrange for appropriate veterinary care, which often will include increased analgesia for pain control, and even elect to euthanase the animals if the suffering cannot be controlled, or when the adverse events compromise the collection of scientific data. Note that the veterinarian’s opinion trumps the PI’s view and the animal’s welfare is the key priority; not the collection of research data. This is how the institutional system has to be set up, to ensure that welfare is not compromised. 4. In the event of major survival surgeries, where the potential for adverse effects is high, many AECs put in place a series of ‘site visits’ to observe animals post-surgery for themselves. 5. In some cases, the AEC will visit the research lab to observe the surgery itself. Such visits can readily identify any variation/ deviation from the approved AEC application and also quickly identify the skills of the surgeon. In my experience, such visits are generally helpful and supportive and give additional advice and recommendations for refinements to assist the PI and the students and thereby further promote animal welfare. Such visits review the post-op monitoring sheets and systems to be used by the PI and student. 6. In some cases the AEC makes unannounced visits to the research laboratory to observe animals. Given the practical limitations of staff, time and budgets, most AECs will target the procedures which have the potential for compromised welfare. For example; visits to animals which have had major heart surgery are a far more useful exercise than visits to animals which have been treated with a single dose of a drug which has few or no side effects. 7. Another monitoring strategy which is not well understood by the public is the system which involves Laboratory Animal Technicians (LATs). In large well managed animal research facilities around the world, LATs are the trained professionals who operate at the front line: at the ‘cage face’. Their role is to care for animals 7 days a week. Note that these facilities are operated 365 days a year. LATs are trained to identify pain behaviours (as detailed above in #1). The LATs work closely in conjunction with the institutional veterinarian and the facility managers. 8. The system works like this. Sally the LAT has found a sick rat on Sunday morning at 8.30am. The rat had surgery on Friday. Sally weighs the rat and checks its post-op monitoring sheet. She quickly calculates that it has lost 14% of body weight. She calls the ‘on-call’ veterinarian and the veterinarian arrives in 30 mins to help. The veterinarian completes a physical examination and decides on a course of action. The PI is contacted at home (because the veterinarian has copies of all AEC documents which include the PI’s contact details- precisely for this sort of problem) and the issue is dealt with. It might involve the PI coming into the animal facility, or it might involve the veterinarian deciding on euthanasia on the spot. In my experience, following euthanasia, the veterinarian would contact the chairperson of the AEC, even on the weekend, and advise them that this event had occurred. It would be well documented and discussed by the AEC soon after the fact. 9. In a well-run animal facility, these LATs are the eyes and ears of the Veterinary staff. In my experience the LATs report approximately 90% of the clinical problems. 10. The ANZLAA organisation (Australian and NZ Laboratory Animal Association) is group of professionals, both LATs, veterinarians and facility managers, whose main function is to promote the welfare of laboratory animals. ANZLAA has an annual conference and NZ participation in this association is active and vigorous. This is the group of personnel who have dedicated themselves to animal welfare in research. They are all career animal welfarists. 11. There are guidelines for AEC and PIs on monitoring: a. National Animal Ethics Advisory Committee (NAEAC) Occasional Paper No 4: Compliance Monitoring: The University of Auckland approach. b. NAEAC No 5: Monitoring Methods for AECs c. NAEAC No 2: Regulation of animals in research, testing and teaching in NZ; the black, the while and the grey d. NAEAC No 3: Regulation of animal use in research, testing and teaching : Comparison of NZ and European legislation e. The Good practice guide for the use of animals in research, testing and teaching. June 2010. Published by MAF. 12. All these documents are available to the public. 13. In summary, in my experience, the monitoring of animals used for research is a well-orchestrated and detailed process which involves many personnel, all working on trust together. In well managed facilities the system is very effective. But we recognise that it is not perfect, but neither is the welfare of all children; some kids don’t get to the GP when they should. 14. The NZ AEC system has a number of checks and balances which appear to manage animal welfare well for the most part. Our system is recognized internationally as being highly regarded. Comments made by Dr John Schofield; BVSc, DACLAM; former Director of Animal Welfare at the University of Otago. John is a veterinarian and a specialist in Laboratory Animal Medicine. 9/12/13 John Schofield <johnawo@xtra.co.nz>