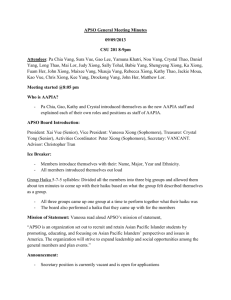

1911 17.3 KB

advertisement

1911: The Lives of Three Young Republican Revolutionaries This year in October China celebrates the centennial of the 1911 Republican Revolution. To better understand the significance of this revolution, consider how it affected the lives of three young revolutionaries from Hupei province: Xiong Shili, Wang Han, and He Zixin The three childhood friends received their early educations from teachers who imbued them not only with traditional Confucian ethics but also with love of country and the need for reform. The writings of a group of scholars in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, known collectively as the Ming loyalists, stressed the need for reform and these writings greatly influenced Xiong, Wang, and He. In their late teens, the three decided on principle not to take the imperial exams that were still the principal means to success, power, and wealth. Instead the three traveled to Wuhan city, the Hubei provincial capital, to join the nascent anti-Manchu revolution. Given their youth and the education that the three had received, many of their family and friends considered their refusal to participate in the imperial exam system foolhardy, but family and friends could not dissuade the three from fomenting revolution. The three young patriots adhered to the Ming dynasty scholar Gu Yanwu, one of the Ming loyalists, who admonished his countrymen that “even the humblest man has a responsibility for the fate of his country.” In Wuhan the three quickly involved themselves in revolutionary work. Wang and He joined the Science Study Group, the first revolutionary organization in Hubei Province. The Group overtly taught science and covertly taught revolution. When the Qing authorities raided the Society for the Revival of China, the nationwide revolutionary group headed by Huang Xing, Sun Yat-sen, and other famous 1911 revolutionaries, they learned the covert nature of the Science Study Group and quickly closed it down. Xiong joined the Qing imperial army in order covertly to propagate revolution among the troops. Xiong’s was an especially sensitive and dangerous undertaking but one that later proved crucial to the success of the 1911 Republican Revolution: without the support of the Imperial troops, the 1911 Revolution would have failed. After Huang Xing and another famous revolutionary, Song Jiaoren, arrived in Wuhan, Wang Han discussed his plan to assassinate a Qing finance official traveling in Hubei to extort money to prop up the failing Qing dynasty. Song Jiaoren supplied Wang with a pistol. Wang shot at the official as he alighted from a train but the shot missed and Wang fled the scene. Unable to evade the dragnet set for him, and fearing that capture and the torture that would ensue might force him to reveal the names of other revolutionaries, Wang committed suicide. News of Wang’s death made He and Xiong even more determined to advance the cause of revolution. Together the two founded the Society for the Daily Increase of Knowledge which they operated out of the reading room of the American founded Episcopalian Church in Wuhan. Every Sunday a meeting was held in the church during which Xiong and He gave lectures on the world situation and China’s critical political and economic condition. Xiong also established a clandestine revolutionary organization for students and soldiers named the Huang’gang County Soldiers’ and Students’ Tutorial Society. The Society pretended to be just another of the many similar county benevolent organizations but the Society, which welcomed members from anywhere in China, not just Hung’gang County, propagated revolution. The Society held meetings on Sundays during which Xiong lectured on nationalism, democracy, and local autonomy. So that the semi-literate soldiers, as well as the better educated students, who attended these lectures could better understand the largely western concepts of civil society, democracy, economics, and so on, Xiong based these lectures on classical Confucian works and the works of the Ming loyalist scholars, such as Gu Yuanwu mentioned above. Putting western concepts in a Chinese context made the concepts easier for Xiong’s audiences to grasp, made them appear less foreign, and lent them cultural legitimacy. Xiong also distributed revolutionary propaganda such as People’s Paper and the Revolutionary Army. 1 This latter work advocated the violent overthrow of Manchu rule and the establishment of a republic with a constitution similar to that of the United States. Xiong’s Society distributed this revolutionary material so efficiently that every soldier had a copy of some revolutionary pamphlet. The Qing authorities, after learning of the Society’s revolutionary work, had it surrounded. Xiong escaped but He was arrested, tortured, and jailed. He escaped from the jail and went into hiding, but torture and internment had broken his health and he died a short while later. The Qing authorities especially wanted to capture Xiong because he propagated revolution among the imperial troops. Xiong had a price put on his head that forced him into hiding until 10 October 1911. At that time, Xiong played a central role in the Wuhan uprising that became the 1911 Republican Revolution that ended 2000 years of imperial rule in China. The revolution, however, had exacted a high price from the three boyhood friends: Wang Han and He Zixin lost their lives because of their revolutionary activities while Xiong nearly lost his. In his memoirs, Xiong made three points about the 1911 Revolution. First, many revolutionaries thought that the revolution would occur in China’s coastal provinces where western influence was deeper than in the backward heartland. It was Wuhan, a city in the very heart of the heartland, however, and not a coastal city, where the revolution started. Second, the Qing troops supported the revolution because it was explained to them in traditional Chinese cultural terms (i.e. the Confucian emphasis on reform and justice as well as the works of the Ming loyalist and Qing reformist scholars). The army’s support proved crucial to the revolution’s success. Third, many of the revolutionaries had failed to appreciate the need for reform, however, and remained what Xiong termed “latent feudalists.” 2