- Surrey Research Insight Open Access

Choreographing the Posthuman

: A Critical Examination of the Body in Digital

Performance by

Seok Jin Han

Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

School of Arts

Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences

Dr Melissa Blanco Borelli (Principal Supervisor)

Dr Nicolas Salazar-Sutil (Co-Supervisor)

© Seok Jin Han

June 2015

59262 Words

Declaration

This thesis and the work to which it refers are the results of my own efforts. Any ideas, data, images or text resulting from the work of others (whether published or unpublished) are fully identified as such within the work and attributed to their originator in the text, bibliography or in footnotes. This thesis has not been submitted in whole or in part for any other academic degree or professional qualification. I agree that the University has the right to submit my work to the plagiarism detection service

TurnitinUK for originality checks. Whether or not drafts have been so-assessed, the

University reserves the right to require an electronic version of the final document (as submitted) for assessment as above.

Signature: __________________________________

Date: 08 June 2015 _______________________

1

Abstract

In the field of dance, the advent of the virtual and robotic body of a human performing subject pushes choreography in new dimensions since these nonhuman presences bring into question how they engage with the perceptual and embodied experience of the human subject. To resolve this question, this thesis analyses selected digital performances where choreographic composition is employed in creating the posthuman, addressing how the human body is engaged with its technological self and vice versa, and then how these choreographic practices evoke ideas about the posthuman subject and its embodiment. For the analyses of the case studies, I draw upon critical posthumanism and post-Merleau-Pontian phenomenology as a theoretical framework, which helps the posthuman escape from an anthropocentric humanist bias against technology’s physical and cognitive ability as a threat to humanity and from a popular posthumanist desire for the disembodiment and transcendence of the body.

This thesis argues that in the case studies the choreographers manifest the posthuman, as an alternative and affirmative vision of the human, which resists an anthropocentric view on the nonhuman as the ‘Other’ or something to control. Instead, they rethink technology as a constituent part of the construction of human subjectivity, while reframing choreographic knowledge of human embodiment as a synthesis of corporeal and digital thoughts. Posthuman embodiment in the choreographic works urges us to rethink the notion of the anthropocentric and Cartesian human subject in terms of the human’s relation to machine, and re-inscribes the body’s doubled condition of presence and absence in the experience of the (physical and/or virtual)

2

world. Also, the case studies reveal the validity of choreographers’ specialised knowledge of bodily ways of being-in-the-world in a posthuman age and the possibility of expanding their knowledge into further domains.

3

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my principle supervisor Melissa

Blanco Borelli for her consistent support, patience with my writing and enthusiastic encouragement that she offered, from the beginning to the end of this extended journey. This research could not have come to fruition without her generous support. I would like thank my co-supervisor Nicolas Salazar-Sutil for his insightful feedback and advice that helped me pull my thought together and tie up loose ends. I want to acknowledge the advice and insight of my former supervisors, Sherril Dodds,

Alexandra Carter and Rachel Fensham. I also thank to the faculty of the Department of Dance Theory at Korea National University of Arts, Professor Chae-Hyeon Kim,

Professor Young-Il Hur and Professor Kyung-Ah Na, who intellectually inspired me and initially made me decide to follow a research career.

I offer heartfelt thanks to my PhD colleagues in School of Arts at University of

Surrey. I have gained fresh inspiration, motivation and support from our PGR community. I thank all the artists and researchers who kindly agreed to provide me with their valuable materials.

This work is dedicated to my family for their tremendous patience and encouragement and for their strong belief in me. Without them, I would probably not have survived such a demanding period of life. I will forever be grateful for their love.

4

Table of Contents

Declaration .................................................................................................................. 1

Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 2

Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................ 4

Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... 5

List of Illustrations ....................................................................................................... 7

Chapter 1 Introduction .............................................................................................. 8

Chapter 2 Choreography for the Posthuman

2.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 32

2.2 Choreography Beyond Dance ...................................................................... 34

2.2.1 Choreographing Movements in Dance and Performance art ............ 34

2.2.2 The Separation of Choreography and Dancing ................................. 41

2.3 Choreographing an Interface ........................................................................ 47

2.4 Conclusion ..................................................................................................... 57

Chapter 3 A Theoretical Framework for the Posthuman Body

3.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 63

3.2 Beyond the Ontology of Liveness ................................................................ 65

3.3 Re-visioning Humanism in Posthumanism .................................................. 71

3.3.1 Post-anthropocentric Approaches to the Posthuman .......................... 71

3.3.2 Critical Posthumanist Approaches to Human Embodiment ............... 75

3.4 Toward the Posthuman Body in Post-Merleau-Pontian Philosophies ........... 80

3.5 Conclusion .................................................................................................... 88

Chapter 4 An Intersection Between Humans, Robots and Cyborgs

4.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 95

4.2 The Australian Dance Theatre’s

Devolution (2006) .................................... 96

4.2.1 Dancing with Robots and Cyborgs ................................................... 96

4.2.2 Resisting Robots and Cyborgs as the Other .................................... 105

5

4.3 Human’s Animality ...................................................................................... 109

4.4 Robots as Living Organisms ........................................................................ 114

4.5 Therianthropic Cyborgs ............................................................................... 118

4.6 Conclusion ................................................................................................. 125

Chapter 5 The Virtual Double

5.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 131

5.2 The Virtual Double ...................................................................................... 132

5.3 Chunky Move’s Mortal Engine (2008)........................................................ 139

5.3.1 The Co-existence of the Physical and the Virtual ............................. 139

5.3.2 The Virtual Double and its Agency .................................................. 144

5.3.3 Doubled Embodiment of Posthuman Subjectivity ............................ 151

5.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................. 158

Chapter 6 Audience Immersion

6.1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 164

6.2 Discourses on Immersion ............................................................................. 166

6.3 Sarah Rubidge’s

Sensuous Geographies (2003) .......................................... 169

6.3.1 The Emergent Digital Sound as the Dys-appearing Body ................ 169

6.3.2 The Re-embodiment of Inter-/subjectivity........................................ 176

6.3.3 The Merging of Physical and Virtual Space ..................................... 180

6.4 igloo’s

SwanQuake: House (2005/08) ......................................................... 183

6.4.1 Embodied Experiences through the First-person Point of view

Avatar ............................................................................................... 183

6.4.2 The Player’s Disappearing Body ...................................................... 193

6.4.3 The Juxtaposition of Physical and Virtual Space ............................. 198

6.5 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 201

Conclusion ................................................................................................................ 207

Bibliography ............................................................................................................. 217

6

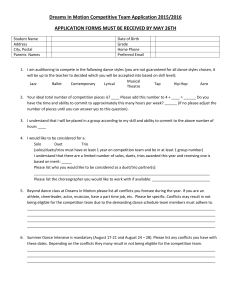

List of Illustrations

Figure 1 White Bouncy Castle (1997) by Dana Caspersen, William Forsythe and

Joel Ryan ................................................................................................ 46

Figure 2 The Fact of Matter (2009) by William Forsythe ....................................... 46

Figure 3 Apparition (2004) by Klaus Obermaier ..................................................... 49

Figure 4 The Spine ................................................................................................... 98

Figure 5 The Cube .................................................................................................... 99

Figure 6 The Bigbots ................................................................................................ 99

Figure 7 The Choir ................................................................................................... 99

Figure 8 The Swarm ............................................................................................... 100

Figure 9 The Spine ................................................................................................. 100

Figure 10 The Body Extensions .............................................................................. 100

Figure 11 A female dancer with an electronic shock .............................................. 133

Figure 12 A duet with diagonal bars of light ........................................................... 133

Figure 13 A cluster of dancers as a giant spider ...................................................... 141

Figure 14 A duet with the smoky trace .................................................................... 143

Figure 15 A man controlling the lasers .................................................................... 143

Figure 16 The installation space .............................................................................. 172

Figure 17 Audience participants’ behaviours .......................................................... 172

Figure 18 Audience participants’ behaviours .......................................................... 172

Figure 19 Inside igloo’s installation at the Barbican Art Gallery, London ............. 185

Figure 20 The dressing table console located in the basement room at V22, London

.................................................................................................................................... 185

Figure 21 The oval mirror frame at the end of the corridor at V22, London .......... 187

Figure 22 The female dancing avatars in the underground warehouses ................. 192

Figure 23 Street view from the roof of the building in the virtual world .............. 192

7

Chapter 1 Introduction

In the history of Western theatre dance, technologies were employed as tools for set designs, lighting and costumes, contributing to the corporeality and theatricality of the human performing body. Since the mid-twentieth century, media technologies capable of recording and reproducing objects have penetrated performance spaces, and projections of film and video images have been embedded in live dance performances

(Dodds, 2004, pp.1-2). Beginning in the 1990s, choreographers have adapted digital technologies such as telematics, 3D images, motion tracking, robotics and artificial intelligence and strived to completely assimilate them into new choreographic practices.

Computer-generated images and sounds and mechanical/robotic products are intertwined with performers or audiences’ corporeal bodies. When choreographers are involved in the creation of the body-technology interface, they often collaborate with experts in other disciplines such as film, new media art, engineering and computer science. The choreographers’ compositional and aesthetic strategies, then, are applied not just to compose physical movements in space and time, but rather to arrange how the physical movements are adapted and reconfigured by mechanical and computer systems. They compose a performer’s biological and mechanical embodiment as a hybrid entity called the ‘posthuman’, or design an architectural environment which instigates audience interactions with machines and makes audiences aware of themselves existing as the posthuman. The intimate and reciprocal relationships between the physical inputs and the artificial outputs are creatively built.

Consequently, distinct boundaries between human beings and machines become blurred in their embodied experiences.

8

Choreographic explorations of technologised bodies are natural and inevitable since digital technologies have encroached upon nearly all elements of our life and impacted on ways of perceiving, thinking and communicating with others. In the new millennium, dance practitioner and scholar Kent De Spain indicates that in a digital age dance is radically redefining itself, as it is able to exist as distinct from its medium of expression, the human body (De Spain, 2000, pp.12-15). The advent of the virtual and robotic body of a human performing subject and the separation of dance from the corporeal body push choreography in new dimensions since, due to the absence of corporeality, these nonhuman presences bring into question how they engage with the perceptual and embodied experience of the human subject. How are virtual and robotic beings created? What role do they play in constructing human subjectivity?

What relationship do they have with the corporeal body? Will they override corporeality? These questions are at stake in choreographic practices in a posthuman age.

To illustrate examples of technological associations with the human dancing body,

Ghostcatching (1999), a ground-breaking installation work co-worked by Bill T.

Jones, Paul Kaiser and Shelley Eshkar, primarily raises an issue of virtual dancing in the absence of the human body. This piece constitutes a multiple of virtual dancing bodies whose movements are initially extracted from Jones’s improvisational moving via a motion capture system and transformed into a three-dimensional moving drawing. The virtual representations of Jones are disembodied beings that do not retain his mass or musculature, but viewers can recognise his presence within the animate beings or his bodily being in a virtual world. Jones also indicates his experience of perceiving the self in a virtual space, stating that ‘when I saw the dots swirling around on the computer screen later, I was mesmerized, and I was quite

9

moved. Because, though there was no “body” there, that was my movement. It was different than video, it was disembodied, but there was something “true” in it’ (Jones, quoted in De Spain, 2000, p.11).

It is not just visual verisimilitude that makes it possible to conceive the virtual being as a newly embodied self because the virtual embodiment of the human subject also takes non-anthropomorphic figures. In the Australian Dance Company, Chunky

Move’s

Mortal Engine (2008), which will be analysed in depth in Chapter 5, kaleidoscopic, liquid, ghostly and geometrical images of digital projections are constantly metamorphosed in real-time response to human dancers’ movements on stage. It is noticeable that the virtual figures emanate from the human dancers by means of the dancers’ motor agency being expanded into a virtual space. The dancers perceive the virtual world and the self through the digital image. What these choreographic practice examples reveal is that Western dualistic assumptions of human and machine, subject and object, physicality and virtuality are challenged since the corporeal body never disappears, but instead engages itself in being-in-thevirtual-world. Also, virtual images become part of the embodiment of dancers’ subjectivities while entwined with corporeal bodies in the experience of the world.

In the early stage of dance-tech practice, Jones made an impressive statement about what attitude dance artists would be required to have in order to be ready for the future: we have to be careful that we don’t get left behind, or that we don’t miss an opportunity to share what we know about the human body and what we love about live performance, share it with the future; and that we don’t become so protective of this little domain that we have which, as we know, is

10

undervalued and underfunded, that we don't have the courage to step out.

(Jones, quoted in De Spain, 2000, p.5)

In the fifteen years since then, Jones’ early cautionary suggestion seems to be well taken by choreographers. In the face of nonhuman performing beings, choreographers apply their special knowledge of the body to the technologised body in consideration of a bodily way of living in the virtual world. They contemplate how the corporeal body is reconfigured into digital information and, in reverse, how this information affects the corporeal body.

In the thesis, I thus intend to argue that choreographic practices involving the nonhuman body and creating the posthuman decentre anthropocentric bias against technology as the ‘Other’ or something to control, and instead rethink technology as a constituent part of constructing human subjectivity. They also re-instate the body as a conduit for embodied experience via a human-computer interface, while reframing choreographic knowledge of human embodiment as a synthesis of corporeal and digital thoughts. These choreographic experiments with nonhuman bodies would lead to the revaluation of the body in human experience and establish the validity of dance in a digital age. To argue that, this thesis aims to analyse selected digital performances where choreographic composition is employed in creating the posthuman, questioning how the human body is engaged with its technological self and vice versa, and then how these choreographic practices evoke ideas about the posthuman.

Choreography and Digital Technologies in Performance

I use the term ‘digital performance’ to name my case studies of choreographic practices that incorporate digital technologies, since the case studies cover not only a

11

broad site for choreographic substantiation but also specifically focus on virtual/robotic forms as part of human embodiment, rather than recorded forms (the difference between the virtual/robotic and the recorded will be discussed later). As critical attention afforded to the intersections of dance and digital media have proliferated since the new millennium, dance scholars and practitioners have attempted to name choreographic practices that utilise digital technologies in various ways, such as ‘computer dance’, ‘cyber dance’, ‘virtual dance’, ‘Internet dance’, ‘edance’, ‘Webdance’, ‘interactive dance’, or ‘telematic dance’, as indicated by

Valverde (2004, p.36).

1

Above all the rest, ‘digital dance’ (Rubidge, 1999) or ‘dancetechnology’ (Valverde, 2004) are most often used as catch-all terms that are not subject to particular technologies used or their effects on dance works. At the end of the twentieth century, British digital performance practitioner and scholar Sarah

Rubidge gave a definition of ‘digital dance’ and traced the development of digital dance works in Britain. She states that digital dance can be defined as a work which

‘must involve the conspicuous use of choreographic concepts as an organising principle, rather than as a means of realising a more general artistic vision’ but which could ‘bear(s) more resemblance to an installation than a dance work, or a work which does not even feature images or representations of the human or anthropomorphic body’ (Rubidge, 1999, p.42). She argues that choreographers or media artists impose a set of choreographic principles upon structuring movements of digital dance works, which are no longer confined to human movements. In comparison with Rubidge, dance practitioner and scholar Isabel Valverde prefers the word ‘dance-technology (dance-tech)’ to denote ‘a transition from being taken for granted as two separate disciplines leading to their hybridization’ (Valverde, 2004, p.38).

2

Valverde admits the problematisation of using the word ‘dance-tech’, pointing

12

out the controversy in considering a choreographic work in a digital interface as

‘dance’ since the application of digital apparatus provokes choreographers to change not only the site for the presentation of dance production, but also the subject of embodiment (Valverde, 2004, p.36).

Rubidge and Valverde suggest the different terms to designate choreographic engagement with technological devices, but both of them implicitly acknowledge that choreography as a mode of thought oriented toward the body in space and time is able to separate from dancing and detach its locus of substantiation from the body.

Reflecting Rubidge and Valverde’s perspectives, I assert that choreographic practices are no longer restricted within theatrical spaces and can take place within installation works that do not involve professional performers or even within web-based platforms or video/computer games where users’ disembodied selves are present.

These choreographic productions then may not be regarded as dance performance, but rather are conceived as media art or installation work. In case studies of this thesis, an intersection between choreography and technologies not only produces a dance performance, but results in an interactive installation, a video game, and a robot performance. This is the first reason I position my case studies within the context of digital performance.

As a matter of fact, however, there has also been ‘a haemorrhaging of nomenclatures’ in theatre and performance studies (Klich and Scheer, 2012, p.11) to describe performances incorporating digital media − virtual theatre, cyborg theatre, multimedia performance, intermedial performance, digital performance and so on.

Each of the nomenclatures commonly encompasses a broad range of technologically mediated performances, but defines the distinct scope and parameters of the field.

The term ‘virtual theatres’ was coined by Gabriella Giannachi and used for the title of her

13

book published in 2004. She positions virtual theatres within the context of interactive arts practices, excluding live performances utilising digital technologies alongside the live performers within the scope of virtual theatres. Virtual theatres commonly include viewers whose experience of the works are remediated as the viewer is simultaneously present to the real and the simulated world. ‘In the world of virtual theatre, the work of art and the viewer are mediated’ (Giannachi, 2004, p.4, original italics). Giannachi also emphasises that when the viewer’s presence is multiplied and dispersed in various locations, s/he is allowed to not just enter into the work, but also act upon it (Giannachi, 2004, p.11).

Rosemary Klich and Edward Scheer’s use of the term ‘multimedia performance’ extends the boundary of virtual theatre, referring to theatre or performance which employs media technologies as a constituent element of the work and which foregrounds the performative act rather than a linear narrative or a text based one

(Klich and Scheer, 2012, pp.17-18). They define multimedia performance through works spanning from post-dramatic theatre

3

, dance and performance art to video installation and immersive environments, mostly taking place from the 1990s onwards.

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck’s ‘cyborg theatre’ is framed within the domain of multimedia performance as it has narrower scope. Her examples of cyborg theatre are mostly live theatrical performances using video, either analogue or digital, on monitors or projected. Parker-Starbuck’s definition of the term ‘cyborg theatre’ involves recognising a sharper focus on mutual relations and thereby integrations between bodies and technologies within the space of theatre, not necessarily denoting a literal fusing of the two entities (Parker-Starbuck, 2011, pp.6-7).

The term ‘intermedial performance’ refers to live performances that incorporate film, video or digital media. Its concept is articulated by the members of the Theatre

14

and Intermediality Research Working Group of the International Federation for

Theatre Research, in order to mark a notable shift in theatre and performance that produces mutual dependence between different media in a multi-tracked textual composition and dis-/reorients perceptions of the performance. This paradigm and process of the performance is proffered as intermediality which appears in territory inbetween performers, viewers and media involved in the performance (Chapple and

Kattenbelt, 2006, pp.11-12). That is to say, intermedial performance not only denotes performances encompassing analogue or digital media but also emphasises the effect of performance, that is, the change of modes of a viewer’s perception. While intermedial performance entails interplay between different media, ‘digital performance’ requires computer technologies that play a constituent role ‘in content, techniques, aesthetics, or delivery forms’ (Dixon, 2007, p.3). ‘Digital performance’ is a term defined by Steve Dixon and Barry Smith, covering a broad range of performance works, from live dance and theatre performance and performance art to installation art, web-based art, CD ROMs and video games. Digital performance requires having trained performers or audiences/viewers/users who perform or enact performative events. Accordingly, Dixon and Smith exclude ‘non-live’ and ‘noninteractive’ performance forms such as film, television, and video art from the scope of digital performance, although digital technologies are incorporated with these art forms (Dixon, 2007, p.x).

Among these nomenclatures that are employed to describe intersections between performance and technologies, I use the term ‘digital performance’ to define not only the scope of my research that encompasses a range of choreographic forms ranging from a theatrical performance to an interactive installation, a video game and robotic performance, but also the subject matter of my research that specifically focuses on

15

virtual and robotic presences rather than screen-based or recorded presences. This research primarily intends to call into question the ontological status of the human subject, corporeal body and agency distinct from the nonhuman subject, technological body and agency. The virtual body and the robotic body more radically undermine the ontological distinction between human and nonhuman in human experience of the world than mediatised representations of the human performer. As recorded bodies obviously reveal their actual human referent, we can easily notice that the mediatised image originates from the human body and is controlled by human agency. By contrast, virtual bodies having no reproduced image of actual humans with mass and musculature and robotic bodies made of metal, rather than flesh and blood, are seemingly separated from the corporeal body of the human subject. Also, these bodies are often embodied by the joining of human and technological agents, which brings into question how human subjectivity is constructed. To support my case studies which choreograph the posthuman or an environment for becoming the posthuman whose subjectivity is embodied through interplays between materiality in the physical realm and information in the digital realm, I find the term ‘digital performance’ more precise than other terms since computer technologies fulfil a crucial role in manifesting embodiment of posthuman subjectivity.

Methodology

My research on posthuman embodiment through intersections of the body and technology in choreographic practices is certainly not a new research subject. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, a plethora of books have appeared in theatre and performance studies, and many of publications take into account dance or choreographic practices to some extent (Giannachi, 2004; Dixon , 2007; Birringer,

16

2008b; Salter, 2010; Parker-Starbuck, 2011; Klich and Scheer).

4

Compared to theatre and performance studies, dance studies has attracted relatively little critical attention and debate concerning intersections between choreography and digital media with the notable exception of several significant books that focus upon dance-tech practices

(Popat, 2006; Kozel, 2007; Portanova, 2013). Historical, critical and artistic perspectives on how digital media intervenes in the form and content of performance arts have poured into academia, but there has been a scholarly tendency to illustrate a wide-range of past and current aesthetic-technological-scientific experimentations and raise related theoretical issues at the superficial level. Nonetheless, some of the scholars propose distinct theoretical and methodological points of view for critical analysis of dance, theatre and performance practices (Dixon, 2007; Kozel, 2007;

Parker-Starbuck, 2011; Portanova, 2013).

In this thesis, I intend to provide in-depth and substantial analyses of posthuman embodiment in choreographic practices and take a posthumanist and phenomenological approach as a theoretical and critical approach, primarily drawing upon critical posthumanism and post-Merleau-Pontian philosophies. My methodology is influenced by, but distinct from, two leading digital performance scholars’ theoretical and methodological approaches ― Dixon’s posthumanism and Susan

Kozel’s phenomenology. In Chapter 3, I will investigate specific theories of posthumanism and phenomenology, but here address the rationale of my theoretical and critical approach, compared with Dixon and Kozel’s approach.

My posthumanist standpoint was initially inspired by Dixon’s proposition of posthumanism as a theoretical and critical framework for digital performance in the book Digital Performance: A History of New Media in Theater, Dance, Performance

Art, and Installation (2007). The book is described as a history of digital performance,

17

but the author does not merely provide a genealogy of digital performance. The author not only addresses the histories, theories and contexts of digital performance, but also presents specific illustrations of practices which are categorised according to four thematic concerns: the body, space, time and interactivity. Artistic practice examples often involve the relevant critical and theoretical discourses (and vice versa) throughout the sections. When Dixon investigates seminal concepts and discourses surrounding the field, he suggests posthumanism as a more appropriate theoretical framework than postmodern and poststructuralist theories which digital performance scholars tend to rely on. According to Dixon, Jean Baudrillard and Jacques Derrida, key intellectuals in these movements, help contextualise non-hierarchical structure, hypertext system and non-linearity of digital performance. However, he also suggests that it has to be acknowledged that they fundamentally have antipathetic attitudes towards new media technologies. Dixon claims that posthumanism argues for an intimate and integrated relationship of human and machine, which helps digital performance scholars conceptualise the unified subjectivity of the posthuman performers.

Posthumanism resists humanism that assigns the primacy of human ontological existence and epistemology over the nonhuman and upholds an essentialism which reifies the human subject into a fixed category with predetermined and invariable characteristics. From an anthropocentric perspective, the posthuman, whose subjectivity comes into being through a partnership of human and machine, would inevitably evoke scepticism because the increase of the nonhuman’s physical and cognitive ability raises concerns about a potential menace to the human subjectivity, the body and humanity. On the contrary, from the viewpoint of posthumanism as postanthropocentrism, human subjectivity is always co-evolving with nonhuman others,

18

so ‘not all of us can say, with any degree of certainty, that we have always been human, or that we are only that’ (Braidotti, 2013, p.1). Accordingly, in the posthumanist paradigm, the posthuman can be conceived as a new vision of the human whose subjectivity is constructed and embodied through interplays of materiality and information and whose cognitive system is distributed across human and technological agents. The posthuman does not necessarily mean a disembodied being that frees the mind from the body or erases embodied experience, but a new embodied mode of being in which there is no absolute boundary between the body and technology. This posthumanist notion of the posthuman challenges Western dualisms and hierarchical system of the human and the nonhuman, self and other, subject and object, mind and body.

I believe that, for choreographers whose idiosyncratic knowledge is about bodily ways of perceiving and cognising the world and who reject Cartesian notion of the body, the use of technology would never be intended to erase the body and replace it with abstract information void of corporeality, unless they purposely envision an apocalyptic world with anthropocentric concerns regarding the end of the human. In contemporary choreographic experiments with relations between the human and technology, choreographers rather seek ways of experiencing the (physical and/or virtual) world through technological intervention and of reconceptualising what the human body means in a posthuman age. Therefore, posthumanism gives an appropriate stance for examining choreographic practices that allow us to rethink anthropocentric humanist bias towards a nonhuman performer or the technologically meditation of a human performer.

Although Dixon makes a valuable contribution to digital performance discourses in terms of his initial proposition of posthumanism, he overlooks that there are

19

different strands of posthuman theory. Cultural theorist Bart Simon discerns ‘popular posthumanism’ from ‘critical humanism’ (Simon, 2003, p.2). ‘Popular posthumanism’, which is now more often referred to as ‘transhumanism’, tends to lay itself open to the censure of the Cartesian human. Popular posthumanism and cybernetic theories as the ancestor of posthumanism tend to unveil a fantasy scenario in which consciousness can be separate from its biological embodiment, which reinscribes the Cartesian humanist subject (Miccoli, 2010, p.56). For instance, a well-known roboticist Hans

Moravec raises the prospect that human consciousness will be downloaded into a computer (Moravec, 1988). This view on the disembodiment of consciousness conforms to Cartesian dualism of mind and body and replicates, or even stretches, a liberal humanist notion of the human subject in a more apocalyptic context (Hayles,

1999, p.287). Since popular posthumanism calls for the erasure of embodied experience, it does not necessarily account for a bodily way of experiencing and being conscious of the virtual. As the opponent of popular posthumanism, ‘critical posthumanism’ puts emphasis on embodiment, whether in a material or immaterial substrate, and the involvement of bodily perception in experiencing the world. In my posthumanist approach to choreographic practices, in order to avoid falling into the trap of recapitulating the Cartesian subject, I specifically focus on critical posthumanism, and also take phenomenological accounts of posthuman embodiment that help shed light on how the corporeal body affects and is affected by technological bodies in the experience of the world.

Phenomenology develops concerns consistent with posthumanism in terms of anti-essentialism and Cartesian mind/body dualism. This philosophical movement emerges as a revolt against the subject-object and the body-mind dichotomies prevalent in tradition Western philosophy. It attempts to explore the epistemological

20

structure of the human’s experience of phenomena, investigating how things appear to us, which depends on our subjective experience of the things rather than their objective being. Also, in phenomenology, our bodies as ‘the lived body’, which is distinct from the physiological or psychological body, take a key role in the constitution of our subjectivity and the intersubjective engagement with others while experiencing the world and being experienced by the self. Phenomenology expands its philosophical discourse into the understanding of phenomena within their sociocultural context. This approach is called ‘a critical phenomenology’, which mainly explores how ideology, politics and languages impact on the construction and constraints of the human being’s lived body and experience of the world, as seen in feminist phenomenological approaches to gendered embodiment and sexual hierarchy

(Beauvoir, 2009 [1949]; Young, 1993). Likewise, phenomenology can adapt and respond to posthumanist questions of the disembodiment of consciousness and the human being’s domination over the nonhuman.

My phenomenological reflection upon posthuman embodiment mainly relies on

Maurice Merleau-Ponty and his followers, since Meleau-Ponty’s philosophy centres on the body and its impact on human consciousness and perception. In this sense, my research offers parallels with dance practitioner and scholar Susan Kozel’s phenomenological investigation of a relationship between the human body and technologies. In her book Closer: Performance, Technologies, Phenomenology (2007),

Kozel addresses how she performs phenomenology through embodied practices with a variety of digital technologies, including telematics, responsive architecture, motion capture and wearable computers. Her own performance experiences, whether performed or choreographed by herself, are illustrated with consideration of phenomenological reflections, in particular, Merleau-Ponty’s theory. Phenomenology

21

is not just a conceptual system that theorises the structural features of human subjective experience and of objects as experienced, but it is also a distinctive method for studying human life from the inside rather than from an outside, objective point of view. Kozel suggests that the integration of personal experiences with a phenomenological method can be achieved by breaking away from the doctrinaire approach and developing the internal, first-person and subjective methodology as a new paradigm (Kozel, 2007, pp.10-11).

There are two things that distinguish my phenomenological approach from

Kozel’s. First of all, my research intends to provide phenomenological reflections on the performing experience of others rather than my own experience as a dancer or an audience participant. I acknowledge that within dance studies, existing phenomenological approaches to dance count on the use of the phenomenological method: the first-person description of sensuous and immediate experiences of performance without having presumptions and prejudices about performance (Pakes,

2011, pp.34-36). The first-person phenomenological perspective on lived experience enables dancers to address and theorise their own experience of feeling, moving and thinking through the body. However, phenomenology also provides a valuable theoretical frame to understand others’ experiences, as I apply phenomenological philosophies to critical interpretations of dancers and audience participants’ embodied experience with their virtual double or robotic prosthetics. What is important here is that my phenomenological reading of others’ experiences is carried out through my embodied experience of their performances. It means that the performances experienced are shaped by my subjective perception of them even though I try to have some degree of critical distance. Thus, according to phenomenology, the understanding of others emerges within one’s perceptible and intelligent world, and

22

also the understanding of the self is realised in relation to the world and others

(Fraleigh, 1991, p.15). That is to say, my methodology is the second-person and intersubjective, rather than the external, third-person and objective. When Kozel discerns the first-, second-, third-person phenomenological methodologies, she articulates what the second-person phenomenological methodology implies.

Presenting a phenomenological interpretation of someone else’s experience is based on two realizations: the first is that phenomenological philosophy provides the conceptual framework and methodological sketch for interpreting the experiences of others; the second is that the sensibility and interpretive power comes from the physical experience of the phenomenologist.

(Kozel, 2007, p.58)

In this thesis, my critical interpretations of others’ experiences are conducted by adopting a set of related phenomenological concepts to their posthuman embodiment and involving my empathic perception and consciousness of them, without the intention of producing true knowledge from an objective scientific stance.

In addition to my second-person methodological approach, the other differentiating factor between Kozel’s and my phenomenological methodology is my posthumanist perspective. For me, Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy reinscribes dualism by assigning a priority to the body/human over the mind/technology and maintaining a subtle ontological distinction between the biological and the technological, which will be examined in Chapter 3. My phenomenological reflections on posthuman performing bodies adopt Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy, but to be accurate, rely more on post-Merleau-Pontian philosophies, some of which directly interrogate the relationship of human beings and technology in the lived experience of the world

23

(Ihde, 1990, 2002, 2008; Verbeek, 2005, 2008, 2011; Hansen, 2006). In particular,

Peter-Paul Verbeek and Mark Hansen give me the critical framework for articulating how a bodily way of being-in-the-world is rearranged or redeployed through technology and its agency, and for avoiding denigrating technology’s intentionality and capability to experience the world. My critical posthumanist and post-Merleau-

Pontian phenomenological approach is primarily an anti-dualistic framework that refuses an anthropocentric bias against technology as the external and a popular posthumanist desire for the disembodiment of consciousness. This approach helps better understand the entanglement between the body and computational systems in the human experience of the (physical or virtual) world, with emphasis on a technological being as part of the human being’s lived body and its embodied experience.

Structure of the Thesis

This thesis begins with ‘Choreography for the Posthuman’ which re-evaluates an orthodox sense of choreography and expands its notion to the design of a humancomputer interface in the context of digital performance. In a historical sense, the term ‘choreography’ means a movement compositional system for dance.

Choreographic practice exists as dance performance and its production is presented through the human body and its movement. The contemporary notion of choreography is, however, no longer exclusively used to name an activity of making dance as it is conceived as a referent for devising an object, an installation, and performance art. In digital performances, choreographic thoughts and methods are substantiated for designing even an immaterial environment, that is, an interface where humans interact with computers. In this chapter, I examine how the notion of

24

choreography has been reframed in terms of the expansion of the site for its substantiation and the reconfiguration of choreographic knowledge itself. In so doing,

I argue that in order to choreograph an interface, the existing choreographic knowledge of the human being’s bodily way of perceiving and embodying the world and the self is reconfigured, as combined with a computer system.

Chapter 3, which is entitled ‘A Theoretical Framework for the Posthuman Body’, draws upon a variety of critical and philosophical discourses that help conceptualise a networked, virtual or robotic being as part of the human being’s doubled or hybrid being. This scholarship ranges from performance studies scholars such as Peggy

Phelan and Philip Auslander, to posthumanist scholars such as Donna Haraway and

Katherine Hayles, to phenomenologist philosophers, in particular, Maurice Merleau-

Ponty and his followers such as Drew Leder, Don Ihde, Peter-Paul Verbeek and Mark

Hansen. This chapter brings to light an anthropocentric bias against mediatised, virtualised and cyborgian representations of the human performer, revealing how the integration of technologies and corporeal bodies calls into question hierarchical dualisms between bodily presence and absence, liveness and mediatedness, physicality and virtuality. In examining the aforementioned theories, I propose critical posthumanism and post-Merleau-Pontian phenomenology as my theoretical and critical standpoint through which to interpret technological entities (the robotic and the virtual) and their entanglement with the human performing subject in choreographic practices.

Based upon the reframed notions of the human body and choreography, the following three chapters conduct analyses of choreographic practices in the digital performance context that feature different types of human-machine interactions

(performer-robot, performer-digital image and audience-digital sound and image) and

25

embrace distinct types of performance environments (theatrical performances or interactive installations). The digital performance example that I select for each of the chapters raises distinct issues: cyborg and robot, virtuality and immersion, respectively. In the case studies, I look into how professional performers, or audiences, become posthuman during their experience of the works. I focus on what forms of inputs and outputs are engaged in an interface and what relationships between the two are established. I will then examine, from an anti-anthropocentric and anti-Cartesian point of view, how the human-machine interactions presented in the performance examples challenge dualistic assumptions of the human subject, the corporeal body and reality.

I acknowledge that there are many ways of embodying the posthuman in the context of digital performance, which primarily hinges on who interacts with what.

The human subject, who can be a professional performer, an audience member or an online user, has its technological self in the form of a telematic or animated image, a digital sound or robotic prosthetics and encounters others while exploring a physical, virtual or mixed environment. Some works present real-time interfaces between human and nonhuman beings during performances while others use the ‘delayed’ interfaces (Valverde, 2004, p.42), often with motion capture technologies which capture performers’ movements and processes and edit them before being presented to the public. Susan Kozel points out that a human-computer interface used during or prior to performances has a different aesthetic impact on the works. However, for

Kozel, a real-time processing of motion capture systems and their possible accidents of ‘imprecision, indecision, or “swithering”’ assign a sense of autonomy or agency to nonhuman beings (Kozel, 2007, p.234).

In keeping with Kozel’s perspective, I find that a real-time human-computer

26

interface more effectively and evidently manifests that technologised beings are not just the disembodiment of the human subject, but part of its doubled embodiment that results from the contamination of the corporeal and the technological. Accordingly, for case studies of this thesis, I select digital performance works that possess a real time interface, apart from Devolution . Metallic robots and prostheses emerging in

Devolution are technically not capable of responding to human performers and perform as pre-programmed. To date, robotic performances presenting real-time interface between human performer/audiences and robots which may have their own agency or may be directly controlled by operators have rarely taken place at theatrical settings, as compared with galleries, museums and trade shows. Nevertheless, I find it pertinent to cast light on robotic beings in Devolution as the work features robotic beings not just as part of posthuman subjects, but also as nonhuman others. This work offers a space for consideration of whether the human and nonhuman robots can make a balanced alliance.

On the basis of the above, in Chapter 4 ‘An Intersection between Humans, Robots and Cyborgs’, I will look into Australian Dance Theatre’s Devolution (2006) which present three types of performing entities: humans, robots and cyborgs. By metaphorically transforming dancers and industrial robots into creatures, the work rejects the dramatisation of a robot invasion and the battle of human beings against robots and instead manifests human dancers and metallic robots as co-existing equal living organisms. The collapse of an opposite relationship between humans and robots is not just metaphorically represented but also literally actualised through the incorporation of robotic devices into the body. Robotic prostheses are attached to the dancers’ bodies, which makes them exist as therianthropic cyborgs. By reflecting upon animal studies, science studies and phenomenology, I investigate how these

27

organic, metallic and hybrid performers that metamorphose into zoomorphic and therianthropic beings challenge humanist assumptions about technology as Other. In so doing, I insist that the work manifests the collapse of anthropocentric dualism and hierarchy of the human over nonhuman others including animals and robots.

In Chapter 5 ‘The Virtual Double’, I shift my focus away from metal embodiment of a human subject to its virtual embodiment. In Western society, cultural connotations of virtuality are built on Cartesian dualism between body and mind, the physical and the virtual, strongly influenced by William Gibson’s notion of cyberspace where the body is substituted with or surpassed by information. Gibsonian cyberspace has been largely adapted and delineated in computer science, popular culture and arts, while in critical theory it has been criticised for not just subordinating the body to mind but obliterating the body. I oppose the concept of Gibsonian cyberspace that radicalises Cartesian dualism, but at the same time intend to avoid reinscribing dualism that prioritises the corporeal over the virtual, which is caused by delimiting the body to its sensory-perceptual aspects and dissociating it with its cognitive and abstract aspects. In this chapter, I reveal that virtuality is not disembodiment but re-embodiment of physicality, by analysing Chunky Move’s

Mortal Engine (2008). Drawing upon Mark Hansen’s concept of ‘bodies in code’, I examine the ontological implications of the virtual double and its chaotic behaviours enacted by its own autonomy in relation to dancers’ embodiment and agency in a virtual environment. In investigating how the dancers contaminate their virtual double

(and vice versa) in light of Drew Leder’s theory of bodily disappearance and dysappearance, I argue that the dancers’ doubling in the physical and the virtual represents a unified subjectivity.

In Chapter 6 ‘Audience Immersion’, Leder’s theory is again employed in

28

investigating how audiences in two installation works ― Sensuous Geographies

(2003) and SwanQuake: House (2005/08) ― are immersed in the virtual environment which is coupled with the physical environment. In a multi-user installation Sensuous

Geographies , co-created by Sarah Rubidge and Alistair MacDonald, audiences create their own sounds through their individual movements and also communicate with other participants through their sounds. In exploring the virtual soundscape shared with others, their perception and awareness of their own bodies in the physical environment are enhanced by a range of haptic materials placed in the installation space. By contrast, in Igloo’s 3D computer graphic installation

SwanQuake: House , when audiences inhabit and navigate a game environment through the eyes of their avatar, they are prompted to shift their attention to their presence in the virtual world.

Juxtaposed with the virtual space, their experience of the physical space gives rise to the confusion of being in the physical and the virtual and subsequently enhances the

‘real’ of the virtual space in their perception. I will explore how the respective audiences in the two installation works experience a computer-generated environment in different ways, in light of bodily ‘dys-appearance’ and ‘disappearance’. In doing so,

I reveal that both of the installation works enhance the audiences’ immersion in the virtual environment through their relationship with the physical environment, which engenders the obscurity of the distinction between the physical and the virtual.

In conclusion, I point out that choreographic explorations of the potential of technology can be differently interpreted, depending on one’s point of view. From my posthumanist perspective, through the disembodiment of the corporeal body in a virtual world and the cyborgisation of the human, choreographers neither offer a dystopian nor utopian vision of a posthuman future. Rather, by manifesting the posthuman as the possibility of human beings, choreographers explore changes of

29

ways of perceiving and embodying the self and the world through the entwinement of the body and technology. In these practices, the human co-evolves with nonhuman others, and technology makes a reconciled and dynamic partnership with the body for the construction of human subjectivity. I argue that this posthuman subject manifested in the choreographic works urges us to rethink the notion of the anthropocentric and

Cartesian human subjectivity in terms of the human’s relation to machine, and remind us of the body as a primary medium for experiencing the world, whether the physical or the virtual. Also, I claim that these choreographing practices that create the posthuman prove the validity of choreographers’ specialised knowledge of bodily ways of being-in-the-world in a posthuman age and the possibility of expanding their knowledge into further domains.

30

1

Valverde enumerates these terms that denote specific features and contexts of computer technology that are used, although there is considerable overlap in the use of these terms.

2 Valverde presents a typology of dance-technology practices with depth analyses of selected examples, examining the four most prominent tendencies within the dancetech interface − the univocal, random, faceted and reflective interface (Valverde,

2004). Each of them has different focal points in terms of the representation and experience of the dance-tech interface, addressing one visual, or aural, representational form (the univocal Interface), multiple representational forms (the random interface), a political content (the faceted Interface) or an interactive environment (the reflexive Interface).

3

‘Postdramatic theatre’ is a term coined by German theatre scholar Hans-Thies

Lehmann to define prominent theatre forms emerging from the 1970s to the 1990s.

Postdramatic theatre, as the epitome of postmodernism in theatre, refuses to adapt the play-text and incorporates media, primarily filmic or video images along with the live performers. Lehmann highlights the impact of media on aesthetics and forms of theatre, stating that the ‘spread and then omnipresence of the media in everyday life since the 1970s has brought with it a new multiform kind of theatrical discourse’

(Lehmann, 2006 [1999], p.22, original italics).

4

Only single-author books are enumerated here, but many anthologies of performance and technologies have been published as well.

31

Chapter 2 Choreography for the Posthuman

2.1 Introduction

In Sarah Rubidge’s

Sensuous Geographies (2003), audiences are invited to engage in an installation space where their individual and collective behaviours are transformed into data, which generates sound strands. The British choreographer Rubidge aims to encourage the participants to create their own sound signatures through interacting with a computational system and other participants’ sounds. In doing so, the participants become bodily sensation-oriented. She labels the installation work as ‘an emergent choreographic event’, indicating that her choreographic tenor is embedded not in composing human movements, but rather in designing a performative interface in which corporeal movements and their reconfigurations take place respectively in a physical and a virtual space (Rubidge, 2009, p.362). In other words, for the creation of this installation, her choreographic strategies are deployed in building mutual and dynamic relations between the spatio-temporal dimensions of the audiences’ impromptu movements and multi-layers of emergent digital sounds.

In a historical sense, choreography means ‘the writing of dance’ (Birringer, 2008a, p.118) or ‘the making of dance’ (Butterworth and Wildschut, 2009, p.1), both of which imply a compositional system for dance. Choreographic practice exists as dance performance and its production is presented through the human body and its movement. However, Sensuous Geographies demonstrates the implementation of choreography without execution of a performer’s movements. In this sense, Rubidge regards the work as ‘a new mode of choreographic practice’ (Rubidge, 2009, p.362).

The term ‘choreography’ is no longer exclusively used to name an activity of making dance. Artists from other arts domains, such as visual art, film, and architecture have

32

ingrained choreographic ideas and principles since the 1960s. Furthermore, this term potentially refers to an arrangement of movements outside the arts field, like a salesperson who enacts improvisational choreography (Foster, 2011, p.2). Dance scholar Susan Foster suggests that the current implication of choreography is ‘an inclusive naming of diverse patterning of movement’ (Foster, 2010, p.37), which can be either precisely arranged or improvised, but is always regulated under certain circumstances. The enactment of choreography is expanded from forming and organising movement itself, to designing an object or an environment through which people perceive, move and think in various ways that are planned and desired.

The contemporary notion of choreography as a structural system of human movements in diverse contexts becomes radically challenged in the context of digital performance. Some of the digital performance works, which are selected as my case studies, can hardly be seen as choreographic practices in an orthodox way because they do not necessarily have human dancers, but they instead present digital images and sounds. When choreography is employed for intersections between corporeal and virtual/robotic bodies, it means designing a real time human-machine interface for posthuman performance. Accordingly, in a human-machine interface, choreographic knowledge of the body should be closely associated with computational systems since they have to reflect upon non-human behaviours in correlation to human behaviours.

The significance of the integration of a human body and a computer system in choreographic practices came to the fore in a workshop ‘choreographic computations: motion capture and analysis for dance’ at The International Conference on New

Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME) where it was affirmed that ‘a shared understanding of movement and gesture is evolving to support the application of complex algorithmic procedures to equally complex choreographic creation’ (NIME,

33

2006).

In this chapter, I primarily investigate how the notion of choreography is reframed in the context of digital performance, by tracing historical changes of choreographic approach to the body. This chapter is divided into two parts. The first part contextualises the contemporary meaning of choreography in the arts by illustrating how choreographers employ their unique and complex sets of principles to devise dance performances, objects and installations. The second delves into the entanglement of choreography with a computational system in the context of digital performance. Based on the re-evaluation of the orthodox sense of choreography examined in the first part, I will argue that when choreography is employed in designing a human-machine interface, it implies not only the separation of choreography from dancing or the human body but also the reconfiguration of choreographic knowledge of the human body itself.

2.2 Choreography beyond Dance

2.2.1 Choreographing Movements in Dance and Performance Art

In her latest book Choreographing Empathy (2011), Foster explicitly examines how the notion of choreography has changed through different historical contexts, according to the advent of new dance forms. From an etymological point of view, the term ‘choreography’ originates from two Greek words:

choreia (the production of movement, rhythm, and voice) and graphie (the act of writing) (Foster, 2011, p.16;

Barthes, 1985). The term ‘choreography’, as the synonym for orchesography, was first introduced in Roul Auger Feuillet’s classic treatise on dance notation Choréographie

(1700).

5

By the eighteenth century, choreography was used to refer to a system of

‘reconciling movement, place, and printed symbol’ (Foster, 2011, p.17). Also, a

34

choreographer was a person who was able to read and write a dance score. In the middle of the eighteenth century, the invention of pantomime ballet, highlighting facial and gestural expressions of characters in a plot, brought about an ontological problem since there was no distinction between movements and notated symbols. The inadequacy of the notation system to convey mimetic and dramatic movements of pantomime ballet entailed the separation of choreography and dance notation.

Throughout the nineteenth century, choreography no longer meant documenting a dance by assimilating movements into abstract and value-free principles, but it was still indiscriminately conceived as the process of training, creating and performing dance (Foster, 2010, p.35).

In the early twentieth century, the growth of modern dance in the United States led to a realisation of the necessity of emphasising choreography as the unique act of creating movements imbued with representational and emotional expressions (Foster,

2010, p.35). Moreover, the choreographed movements began to be considered as the essential nature of dance, while contributing to securing the authority of dance, giving it equal status with other art forms (Lepecki, 2006, p.4). For instance, Martha Graham, often called ‘the mother of modern dance’, considers the moving body as an instrument to express her artistic message, mainly associated with the human spirit and emotion, which can be personal but at the same time transcendental. In Graham’s works, a dancer’s body has to be technically disciplined to enact emotional characters.

According to John Martin, a theorist, critic and advocate of modern dance, it is not before Graham that dance established its ontological ground, which rested on movements in which choreography took place (Martin, 1933, p.6). For Martin, in

Romantic and Classical ballet, movements were bounded by narrative structures and the strict rules of ballet techniques. Even Isadora Duncan, known as a pioneer of

35

modern dance, was inclined to view movements as subject to music. Martin asserts that in order to be accepted as an art form in its own right, dance should be aligned with movements that represent individual and universal concerns through choreography as a unique process of dance (Martin, 1933, p.6).

Since the 1960s, on the other hand, the meaning of choreography has not been confined to inscribing movements into the bodies, but it has extended to setting a structure which instigates the bodies to move, in response to the designed environment. Emerging at the Reuben Gallery and the Judson Church in New York, postmodern dance as the antithesis of stylised and expressive movements of modern dance tended to claim distinct artistic initiatives to modify a compositional procedure and to extend beyond a theatre space as the site for performance. The postmodern choreographers in the 1960s and 1970s had individual aesthetic concerns and methods, but shared common ground regarding what choreography means in their works. They intended to abandon movements that represent someone or something else and instead present the body itself as a message. Their choreographic focus is on investigating how and why movements proceed, rather than what the movements display. These movements, then, are not required to be in harmony with music or to be conducted in a stylised manner with technical virtuosity. Instead, the choreographers devise how pedestrian movements and everyday gestures are arranged and combined by using task-oriented and improvisational processes which give rise to physical and sociopolitical awareness.

As an iconoclast, Anna Halprin’s concept of directing rather than choreographing had significant influence on the early generation of postmodern choreographers, such as Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer

6

, Trisha Brown and Steve Paxton

7

. For Halprin, improvisation is the key method to emancipate the body from institutionalised

36

movements of modern dance as well as behaviour patterns affected by anatomical structures and social norms. She encourages dancers to open up their bodies’ capabilities through improvisation which is implemented either in an anatomical way to articulate and re-assemble various body parts or through imagery activities which facilitate the freedom of movement by spontaneous impulses (Banes, 1987, p.22).

One of Halprin’s students, Simone Forti first presented her seminal work

See Saw

(1960) at the Reuben Gallery. In its premiere performance, Rainer and American sculptor Robert Morris performed on a play-like structure which resembled a see-saw.

The two performers did not execute pre-determined movement sequences but instead improvised while finding and losing their equilibrium. In Forti’s dance constructions, such as Roller (1960), See Saw, Huddles (1961), Hangers (1961) and Slant Board

(1961), she sets up minimum rules for performers to accomplish a task which is often associated with a devised object or sculpture. The subtle choreographic principles allow the performers to freely explore the physical features of their bodies that ‘move or be moved by some thing rather than by oneself’ (Rainer, 1968, p.269).

As described above, the early postmodern choreographers in the 1960s and 1970s embrace pedestrian movements that are instigated by objects or through task-based activities. In this sense, their compositional strategies reveal a significant parallel with

Marcel Duchamp’s notion of the readymade 8

that proves that an ordinary manufactured object can become an artwork after it is selected and repositioned by an artist (Lepecki, 2010, p.155). For the early postmodern choreographers, a dance performance is considered ‘as a made event distinct from its execution’ (Foster, 2011, p.62). The role of a choreographer is emphasised in directing the structure and the process in which performers borrow and arrange movements, rather than in creating the movements to express the choreographer’s intention and message. Moreover, in

37

order to aim for open and fluid communications with external conditions and audiences as unpredictable compositional elements, their choreographic practices often take place at non-theatrical sites, such as museums, galleries, outdoor, and public spaces where boundaries between art and life or between a performer and an audience dissolve. Extending beyond the frame of the theatrical environment allows the audience to have close proximity to the performance space and directly involve oneself in the work.

With the change of the function, method and site of choreography, postmodern dance practices in the 1960s and 1970s bear a resemblance to visual arts, in particular, performance art that has had an experimental orientation toward corporeality, ephemerality and movement composition since the end of the Second World War. The term ‘performance art’ came into its own as a distinct form of visual arts in the early

1970s. In performance art, visual artists turn to their own bodies as a medium for materialising their ideas (Goldberg, 2011). Performance can be loosely defined as

‘live art by artists’ (Goldberg, 2011, p.9), but it not only refers to performances which are held in front of audiences but also encompasses ones which are presented through photography, video, film and/or text that record the artists’ operation of the body in public or private settings (Jones, 1998, p.13). Performance art was heralded by a prominent phenomenon, ‘conceptual art’, which emerged in the mid-1960s.

Conceptual artists insist on their ideas or processes which take precedence over objects, while spurning the art market in which the ideas cannot be bought and sold.

Conceptual art provides direct inspiration for performance artists who give priority to a performer’s embodied activity as ‘a demonstration, or an execution, of [their] ideas’

(Goldberg, 2011, p.7), In performance art, ‘the artist’s body becomes both the subject and the object of the artwork’ (Sharp, 1970, p.17).

38

According to RoseLee Goldberg, who wrote pioneering books on performance art, performance art flourished in the 1970s and established itself as a distinct genre of art in its own right. Since the early twentieth century, however, an artist’s engagement with his or her own body has been used as a means of deviating from traditional approaches, such as painting on canvas and sculpting objects and regarded as the vanguard of avant-garde activities (Goldberg, 2011, p.7). Thus, in a broad sense, performance can be traced back to Dada and Futurism

9

in the 1910s and 1920s, embracing a range of art movements, such as Happening and Fluxus 10 in the 1960s,

Performance art and Body art

11

in the 1970s and 1980s, and technologically-mediated body works

12

in the 1990s (Jones, 2000, pp.21-23).

In the world of painting, Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock initially spurred artists to recognise an art-making process as a work of art. Pollock’s actions, such as dripping, spattering and daubing paints on a canvas with a brush while moving back and forth and from side to side, left traces which constituted an abstract painting. The

American critic, Harold Rosenberg, labelled Pollock’s works ‘action painting’ in which the canvas is viewed as ‘an arena in which to act… What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event’ (Rosenberg, 1952, p.22). In action painting, how an artist moves is directly linked to what his or her work is. Hans Namuth’s photography and films documenting Pollock’s creative process take a significant role in emphasising the artist’s bodily action as an essential part of his works, along with the products themselves (Phelan, 2010, p.24). Swayed by Pollock, an increasing number of visual artists have foregrounded their own embodied activities (Schimmel,

1998; Jones, 1998). Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, performance artists tended to eschew ‘the dramatic structure and psychological dynamics of traditional theater or dance’ as well as proscenium stage, but instead bring ‘bodily presence and movement

39

activities’ into focus, in galleries, museums or private studios (Hayum, 1975, p.339), which is what the early postmodern choreographers in the same period wished to pursue. In other words, while the visual artists directed their attention toward their bodies or movements, the choreographers intended to abandon movements pretending to be something or someone in favour of everyday movement, improvisation, and task-based structure. Artistic processes and manners of executing the body or movement in dance and visual art became imbricated.

To give examples of the intersections between the two art forms, Allan Kaprow, the inventor of Happening as a genre of performance art, calls himself an ‘action artist’, advancing Pollock’s concept of ‘action painter’ (Goldberg, 2004, p.17).

Kaprow first performed 18 happenings in 6 parts, often regarded as a symbolic piece of avant-garde performance, in 1959 at the Reuben Gallery in New York. In the work, the sequences of actions of six performers are determined by Kaprow’s prescribed cards which instruct what gesture, timings and steps the performers will enact.

Kaprow’s compositional strategies for Happening and the minimalist approach to movement are aligned with choreographic method and content in Judson Dance

Theater

13

(Solomon, 2010, p.42). Bruce Nauman, the American visual artist, uses a variety of mediums, such as sculpture, installation, photography, film and performance, acknowledging that not only an object, but also an artist’s activity can become a work of art, which largely reflects the key idea of conceptual art (Wallace and Keziere, 1979). For example, his performance piece Walking in an Exaggerated

Manner around the Perimeter of a Square (1967-8) is a ten-minute film that shows himself slowly walking on the boundary of a taped square in his studio and pausing for a bit in an absurd posture just before taking a step forward. The title of the piece literally explains what he is doing on the film. During the repetitive enactment of the

40

simple but precisely controlled activities, he evokes self-awareness and brings a hypersensitivity to mundane movements. For him, there is a resemblance between his performance and dance, which was conceived after having a conversation with

Meredith Monk, the postmodern choreographer and composer.

I guess I thought of what I was doing sort of as a dance because I was familiar with some of the things that Cunningham had done and some other dancers, where you can take any simple movement and make it into a dance, just by presenting it as a dance. I wasn’t a dancer, but I sort of thought if I took things that I didn’t know how to do, but I was serious enough about them, then they would be taken serious.

(interviewed with Sciarra, 2005, p.166)

Nauman proposes the breakdown of the distinct boundary between dance and visual arts, since dance and visual artists share artistic intentions, compositional strategies and performance modes. As the concept of choreography has been expanded, choreographers’ and performance artists’ approaches to the bodily presence have interpenetrated each other. This phenomenon implies that choreography is not necessarily an exclusive term to refer to dance artists’ way of composing an artwork, and also that choreographic practices do not always need to produce dance works.

That is to say, a long-held assumption that choreography belongs to the realm of dance is challenged.

2.2.2 The Separation of Choreography and Dancing

Strongly influenced by early postmodern choreographers, contemporary North

American and European choreographers have radically experimented with the orthodox notion of dance since the mid-1990s, namely La Ribot, Jérôme Bel, Xavier

41

Le Roy, Boris Charmatz, Meg Stuart, Vera Mantero, Jonathan Burrows and Juan

Dominguez, to mention a few. The choreographers whose works are often labelled

‘conceptual dance’ venture to disentangle dance from the moving body and to conceptualise choreography as the object of dance (Cvejić 2006; Cvejić and

Vujanović, 2010).

14