The Enlightenment

advertisement

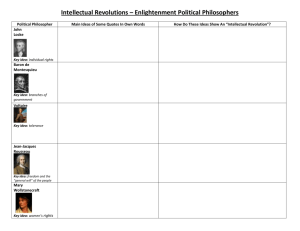

The Enlightenment To understand the natural world and humankind's place in it solely on the basis of reason and without turning to religious belief was the goal of the wide-ranging intellectual movement called the Enlightenment. The movement claimed the allegiance of a majority of thinkers during the 17th and 18th centuries, a period that Thomas Paine called the Age of Reason. At its heart it became a conflict between religion and the inquiring mind that wanted to know and understand through reason based on evidence and proof. Like all historical trends and movements, the Enlightenment had its roots in the past. Three of the chief sources for Enlightenment thought were the ideas of the ancient Greek philosophers, the Renaissance, and the scientific revolution of the late Middle Ages. The ancient philosophers had noticed the regularity in the operation of the natural world and concluded that the reasoning mind could see and explain this regularity. Among these philosophers Aristotle was preeminent in discovering and explaining the natural world. The birth of Christianity interrupted philosophical attempts to analyze and explain purely on the basis of reason. Christianity built a complicated world view that relied on both faith and reason to explain all reality. The Renaissance, with its revival of classical learning, and the Reformation of the 16th century, which broke up the Christian church, ended the world view that the church had presented for a thousand years. Coupled with these events was the scientific revolution, a modern discipline that soon lost patience with religious quibbling and what was seen as the attempts of churches to hamper progress in thought. Among the leaders of this revolution were Francis Bacon, René Descartes, Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and—most significant of all—Isaac Newton. It was Newton who explained the universe and who justified the rationality of nature. John Locke was a British philosopher who lived from 1632-1704. In 1690 Locke published one of his more famous books, The Second Treatise of Civil Government . The book addressed many areas including his views on the state of nature, civil society and the dissolution of government. His writings and beliefs greatly influenced John Locke was a British philosopher who lived from 1632-1704. In 1690 Locke published one of his more famous books, The Second Treatise of Civil Government . The book addressed many areas including his views on the state of nature, civil society and the dissolution of government. His writings and beliefs greatly influenced many later revolutions including the American and French Revolutions. John Locke (1632–1704). One of the pioneers in modern thinking was the English philosopher John Locke. He made great contributions in studies of politics, government, and psychology. John Locke was born in Wrington, Somerset, on Aug. 29, 1632. He was the son of a wellto-do Puritan lawyer who fought for Cromwell in the English Civil War. The father, also named John Locke, was a devout, even-tempered man. The boy was educated at Westminster School and Oxford and later became a tutor at the university. His friends urged him to enter the Church of England, but he decided that he was not fitted for the calling. He had long been interested in meteorology and the experimental sciences, especially chemistry. He turned to medicine and became known as one of the most skilled practitioners of his day. In 1667 Locke became confidential secretary and personal physician to Anthony Ashley Cooper, later lord chancellor and the first earl of Shaftesbury. Locke's association with Shaftesbury enabled him to meet many of the great men of England, but it also caused him a great deal of trouble. Shaftesbury was indicted for high treason. He was acquitted, but Locke was suspected of disloyalty. In 1683 he left England for Holland and returned only after the revolution of 1688. Locke is remembered today largely as a political philosopher. He preached the doctrine that men naturally possess certain large rights, the chief being life, liberty, and property. Rulers, he said, derived their power only from the consent of the people. He thought that government should be like a contract between the rulers and his subjects: The people give up certain of their rights in return for just rule, and the ruler should hold his power only so long as he uses it justly. These ideas had a tremendous effect on all future political thinking. Locke was always very interested in psychology. About 1670, friends urged him to write a paper on the limitations of human judgment. He started to write a few paragraphs, but 20 years passed before he finished. The result was his great and famous ‘Essay Concerning Human Understanding'. In this work he stressed the theory that the human mind starts as a tabula rasa (smoothed tablet)—that is, a waxed tablet ready to be used for writing. The mind has no inborn ideas, as most men of the time believed. Throughout life it forms its ideas only from impressions (sense experiences) that are made upon its surface. In discussing education Locke urged the view that character formation is far more important than information and that learning should be pleasant. During his later years he turned more and more to writing about religion. Locke Quotes All mankind...being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty [freedom] or possessions [things they own]. The end [purpose] of law is not to abolish [end] or restrain [hold back], but to preserve [protect] and enlarge freedom. [A] ruling body [government] if it offends against natural law must be deposed [removed]. For he that thinks absolute power purifies men's blood, and corrects the baseness [immorality] of human nature, need read but the history of this, or any other age, to be convinced of the contrary [opposite]. Discussion Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. Describe Locke’s beliefs. What did Locke believe the role of government should be? How do each of the two visuals support or challenge Locke’s beliefs? What might life be like today had Locke never written about nor promoted his beliefs? Jean Jacques Rousseau, a Swiss-born French philosopher, lived from 1712-1778. While Rousseau authored novels and opera, he is most well-known for his political writings in his 1762 work The Social Contract. Rousseau’s views were not popular with French and Swiss authorities, so he fled to Prussia and then to England. He later returned to France under an assumed (false) name. Rousseau’s political writings greatly influenced later revolutions, including the French Revolution. ean-Jacques-Rousseau (1712–78). The famous Swiss-born philosopher Rousseau gave better advice and followed it less than perhaps any other great man. Although he wrote glowingly about nature, he spent much time in crowded Paris. He praised married life and wrote wisely about the education of children, but he lived with his servant, marrying her only after 23 years, and gave up their babies. He taught hygiene, yet he lived in a stuffy garret. He preached virtue, but he was far from virtuous. Rousseau himself was unable to guide his behavior to follow his beliefs. Yet his writings on politics, literature, and education have had a profound influence on modern thought. Of French Huguenot descent, Rousseau was born in Geneva, Switzerland, on June 28, 1712. His father was a watchmaker. Young Rousseau grew up undisciplined, and at about the age of 16 he became a vagabond. In Chambéry, France, he met and lived with Madame de Warens, a woman who was to influence his intellectual evolution. For a while he roamed through Switzerland, Italy, and France, earning his way as secretary, tutor, and music teacher. When he went to Paris in 1741, he was impressed by the fact that society was artificial and unfair in its organization. The society that Rousseau viewed lived by rules made by the aristocracy and had little interest in the welfare of the common man. This unknown wanderer upset that whole elaborate society. After years of thought Rousseau wrote a book on the origins of government, The Social Contract, stating that no laws are binding unless agreed upon by the people. This idea deeply affected French thinking, and it became one of the chief forces that brought on the French Revolution about 30 years later. He also wrote that people are naturally good, but that environment, education, and laws corrupt them. He believed that people could preserve their natural state only if they could choose their own government. He wrote that good government must be based on popular sovereignty. By this he meant that government must be created by and controlled by the people. Rousseau helped bring about another revolution in education. In his novel Émile he assailed the way parents and teachers brought up and taught children. Rousseau urged that young people be given freedom to enjoy sunlight, exercise, and play. He recognized that there are definite periods of development in a child's life, and he argued that children's learning should be scheduled to coincide with them. A child allowed to grow up in this fashion will achieve the best possible development. Education should begin in the home. Parents should not preach to their children but should set a good example. Rousseau believed that children should make their own decisions. Careful readers of Rousseau find many flaws in his logic, especially in his greatest book, The Social Contract. Rousseau was broad-minded enough to realize that his was not the final word on government. Rousseau’s Quotes Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains. No man has any natural authority over his fellow men. Only the general will can direct the energies of the state in a manner appropriate to the end for which it was founded, i.e., the common good. I prefer liberty with danger to peace with slavery. The English think they are free. They are free only during the election of members of parliament. Discussion Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. Describe Rousseau’s beliefs. What did Rousseau believe the role of government should be? How do each of the two visuals support or challenge Rousseau’s beliefs? What might life be like today had Rousseau never written about nor promoted his beliefs? Francois Marie Arouet, who took the pen name Voltaire, was a French philosopher who lived from 1694-1778. Voltaire spent several years in exile in England, and was influenced by his experience there as well as by his French background. In his early twenties he spent eleven months in the Bastille for writing satiric verses about the aristocracy. Voltaire’s ideas greatly influenced revolutions, including the French Revolution and the American Revolution. Voltaire (1694–1778). In his 84 years Voltaire was historian and essayist, playwright and storyteller, poet and philosopher, wit and pamphleteer, wealthy businessman and practical economic reformer. Yet he is remembered best as an advocate of human rights. True to the spirit of the Enlightenment, he denounced organized religion and established himself as a proponent of rationality. Voltaire was born François-Marie Arouet on Nov. 21, 1694, in Paris. At 16 he became a writer. He wrote witty verse mocking the royal authorities. For this he was imprisoned in the Bastille for 11 months. About this time he began calling himself Voltaire. Another dispute in 1726 led to exile in England for two years. On his return to Paris he staged several unsuccessful dramas and the enormously popular ‘Zaïre'. He wrote a life of Swedish king Charles XII, and in 1734 he published ‘Philosophical Letters', a landmark in the history of thought. Voltaire wrote “I may disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” The letters, denouncing religion and government, caused a scandal that forced him to flee Paris. He took up residence in the palace of Madame du Châtelet, with whom he lived and traveled until her death in 1749. In 1750 Voltaire went to Berlin at the invitation of Prussia's Frederick the Great. Three years later, after a quarrel with the king, he left and settled in Geneva, Switzerland. After five years his strong opinions forced another move, and he bought an estate at Ferney, France, on the Swiss border. By this time he was a celebrity, renowned throughout Europe. Visitors of note came from everywhere to see him and to discuss his work with him. Voltaire returned to Paris on Feb. 10, 1778, to direct his play ‘Irene'. His health suddenly failed, and he died on May 30. ‘Candide', the strongly anti-Romantic comic novel, is the work by Voltaire most read today. In it, he ridiculed prejudice, bigotry, and oppressive government. Voltaire became famous as a champion of freedom of religion and freedom of thought. QUOTES It is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established authorities are wrong. I detest what you write, but I would give my life to make it possible for you to continue to write. (Letter to Monsieur le Riche, 1770) Liberty of thought is the life of the soul. (from Essay on Epic Poetry, 1727) The way the English run their country is excellent. This is not normally the case with a monarchy [government ruled by a king or a queen], but because there is a parliament [elected body of representatives, also known as a legislature], English people have rights. They are free to go where they wish; they can read what they like. They have the right to be tried properly by law, and all individuals are free to follow the religion of their choice. I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God? Discussion Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. Describe Voltaire’s beliefs. What did Voltaire believe the role of government should be? How do each of the two visuals support or challenge Voltaire’s beliefs? What might life be like today had Voltaire never written about nor promoted his beliefs?