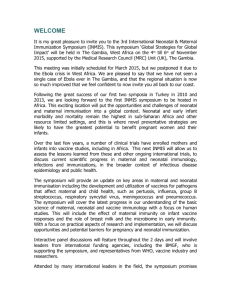

Australia-Indonesia Maternal and Newborn Health and Nutrition

advertisement