Why Literature Matters

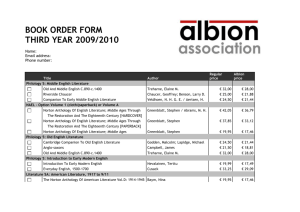

advertisement

Matt Jacobs 18 November 2013 Over the past several months I’ve spent a considerable amount of time thinking about why literature matters, in part to prepare for tonight’s discussion, but also to make sure I haven’t wasted the last two and a half years of my life. The short answer is I haven’t. I initially wanted to come up with something profound and groundbreaking to contribute to this discussion. Either I failed miserably in this endeavor, or it turns out the question doesn’t need a sophisticated or profound answer. I’m still going to save my answer until the end, because it seemed like a solid rhetorical strategy. To some degree or another, all academic ambitions are fueled by a desire to make sense of the world and to understand the human condition. Some disciplines achieve this by dissecting, categorizing, classifying, or otherwise breaking the world into manageable pieces. Literature puts the pieces back together again. Wordsworth beat me to the punch in the Preface to his Lyrical Ballads: “If the labours of men of Science,” he writes, “should ever create any material revolution, direct or indirect, in our condition, and in the impressions we habitually receive, the Poet will sleep then no more than at present, but he will be ready to follow the steps of the Man of Science, not only in those general indirect effects, but he will be at his side, carrying sensation into the midst of the objects of the Science itself.” To put this less eloquently, literature is well equipped and eager to take the work of science and put it back into the context of the world, and to bask in the awesomeness of the world, and to make it accessible. My next observation isn’t entirely different from the last one: literature is all-inclusive in a way that other disciplines aren’t. In my time at Longwood I’ve read historians, philosophers and astronomers. I’ve read biologists, mathematicians, physicists, and anthropologists. Theologians and atheists. Fiction and nonfiction. In most cases, the only common denominator is the fact that everything I read was literature. Stephen Greenblatt recognizes the comprehensiveness of literature in Resonance and Wonder: “My own concern remains centrally with imaginative literature,” he explains, in part “because other cultural structures resonate powerfully within it.” What makes the hard sciences great is the devotion of each science to its respective field of study. What makes literature great is its openness to all fields of study. I would be lying if I claimed that studying literature has always been explicitly rewarding. When I’m on my second pot of coffee, trying desperately to navigate my way through the works of someone as dense as Milton, and discouraged by the fact that most of what I’m reading goes way over my head, it’s easy to dismiss literature as something that’s only important to writers and editors and critics. Maybe literature only matters to the small circle of elite scholars who choose what texts are worthy of the Norton anthologies that are scattered all over my house. I think it’s worth mentioning some of the turn-offs and obstacles encountered in coming to an appreciation of the importance of literature. Writers and critics alike tend to speak in absolutes. This is the way the world works, and everybody else is wrong. Consequently, it’s not hard to find elitism and pretentiousness in the academic and editorial worlds that surround literature – there is little room for modesty. I have a theory that footnotes were invented to make college students feel inadequate. Footnotes are just a way for editors to flex their academic muscles and show off their learnedness at the expense of my ego. Studying literary theory and criticism feels like witnessing a war among scholars. It seems the only way to make a name for yourself is to invalidate the works of previous critics. Whether my observations are true or just products of coffee-induced delirium, literature is far bigger than any one writer or editor or critic. I have learned to see through the isolated instances of academic snobbery, and in doing so I discovered that the literary world is made up of people who love to read, and to write, and to read and write about reading and writing. When it comes up in conversation that I’m studying English, the first question is always, ‘do you want to be a teacher?’ Since I go to Longwood it’s a fair question, but I most assuredly do not. At this point I am left with a patronizing chuckle and, ‘good luck finding a job.’ The joke is on them. I have had one of the most important educations a young person can have in the twentyfirst century. Reading, writing, and critical thinking are skills that I will continue to develop and use regardless of how I make a living. In a last-ditch attempt to connect all of the non-sequiturs: literature matters because it’s something humans do, and it’s something we’ve been doing for a long time. If we didn’t write literature wouldn’t matter. If literature didn’t matter we wouldn’t write. Works Cited Greenblatt, Stephen J.. “Resonance and Wonder.” The Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism. 2nd ed. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: Norton, 2010. 2150-2161. Print. Wordsworth, William. “Preface to Lyrical Ballads.” The Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism. 2nd ed. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: Norton, 2010. 559-579. Print.