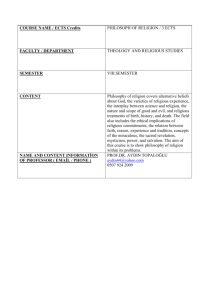

View/Open

advertisement

THE NATURAL DESIRE FOR GOD: KARL RAHNER’S AND FRANS JOZEF VAN BEECK’S RECONFIGURATION OF THEOLOGICAL METAPHYSICS BY MARIJN DE JONG AND PATRICK COOPER 1. Introduction In the early twentieth century, a vehement debate on the relation between nature and grace went on in Catholic theological circles. Theologians maintaining a close affiliation with the neo-Scholastic intellectual tradition were debating with theologians from the so-called nouvelle théologie, who sought to integrate modern philosophical ideas and historical scholarship into theology.1 Their discussion on nature and grace is indicative of an important challenge facing Catholic theology since the beginning of Modernity: to bring its theological metaphysics into critical dialogue with modern thought.2 This paper will review Karl Rahner’s contribution to this debate.3 Rahner shares with other ressourcement theologians the concern to “go back to the sources” in order to free the dynamism of the Christian tradition from neoScholastic constraints.4 More specifically, he engages in a retrieval of Thomas Aquinas that brings the Angelic Doctor in dialogue with modern philosophy. 5 This Describing the opposing schools of thought, Rahner mentions Henri de Lubac, Henri Bouillard, Émile Delaye, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and Henri Rondet as representatives of the Nouvelle Théologie, while he mentions Jacques de Blic, Leopold Malevez, Charles Boyer, Reginald GarrigouLagrange, Guy de Broglie, and Philippe de la Trinité as representatives of the Neo-Scholastic line. Cf. Karl Rahner ‘Über das Verhältnis von Natur und Gnade’, in Schriften zur Theologie (Einsiedeln – Zürich – Köln: Benziger Verlag, 1954), 323-345. 2 For a more detailed account of the nature-grace debate in modern Catholic theology cf. Stephen Duffy, The Graced Horizon. Nature and Grace in Modern Theological Thought (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1992). 3 We will focus on two articles in which Rahner specifically deals with the relation between nature and grace. The first article is ‘Über das Verhältnis von Natur und Gnade’, in Schriften zur Theologie (Einsiedeln – Zürich – Köln: Benziger Verlag, 1954), 323-345 (originally published in Orientierung 14 (1950): 141-145). In the second article, ‘Natur und Gnade’, in Schriften zur Theologie. Band IV Neuere Schriften (Einsiedeln – Zürich – Köln: Benziger Verlag, 1960), 209-236, Rahner takes up again the theme of nature and grace further developing his argument. 4 Cf. Richard Lennan, ‘The Theology of Karl Rahner: An Alternative to Ressourcement, pp. 405-422 in Gabriel Flynn & Paul Murray (ed.), Ressourcement: A Movement for Renewal in Twentieth-Century Catholic Theology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 405. 5 Karl Rahner is known as one of the main representatives of the movement of “Transcendental Thomism”, a current of theological thought that started a revival of Catholic theology at the beginning of the twentieth century. Through renewed historical study of Thomas Aquinas, the transcendental Thomists sought to bring Thomistic philosophy and theology into confrontation and dialogue with modern philosophy and theology. Cf. Francis Schüssler Fiorenza, ‘The New Theology and 1 leads him to develop a dynamic theological anthropology that is grounded in an intrinsic interrelation of nature and grace. Our discussion aims to show that Rahner’s newly conceived theological metaphysics has important consequences for our views on the secular and the religious. Importantly, it pushes us theologians to see our relation to philosophy and other secular academic disciplines in a different light. 2. Overcoming Extrinsicism Rahner starts with a critical assessment of the Neo-Scholastic view on grace, which emphasises the distinction between the natural and supernatural orders. According to this view, the supernatural is not encountered in ordinary natural life. Rather, grace is imposed on nature as a “superstructure" by the purely external divine decree of God. The relation between nature and grace is conceived so negatively that nature’s ordination towards grace – its potentia obedientialis – can be characterised merely negatively as “non-repugnance”.6 Rahner finds this position highly problematic as it presupposes a dualism of nature and grace that leads to an extrinsic conception of grace. How are people to be interested in the mysterious dimension of grace, if they do not encounter it in everyday existence?7 Rahner’s critique of neo-Scholasticic extrinsicism clearly manifests his engagement with contemporary philosophy, particularly Martin Heidegger’s existentialism.8 Prefiguring the Second Vatican Council, he advocates that theology should be in conversation with the “mentality of the present day”. For Rahner, this means taking up contemporary existential concerns, i.e. explaining how grace affects human existence.9 He sees a direct cause for the rise of modern naturalism and secularism in the extrinsicist metaphysical position on nature and grace. Since the Transcendental Thomism’, in James C. Livingston & Francis Schüssler Fiorenza (ed.), Modern Christian Thought, Volume 2 The Twentieth Century (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2006), 197-232. 6 Rahner, ‚‘Über das Verhältnis’, 323-325; Rahner, ‘Natur und Gnade’, 210-212. 7 Rahner, ‘Natur und Gnade’, 213; Rahner ‘Über das Verhältnis’, 326. Rahner refers to Henri de Lubac’s Surnaturel as an example of an account of the historical and spiritual consequences of the neo-Scholastic view on nature and grace. Cf. Henri de Lubac, Surnaturel: études historiques (Paris: Aubiers Editions Montaigne, 1946). Additionally, the Neo-Scholastic position with its insistence on the possibility of “pure nature” in concrete existence involves an inadequate ontology. According to Rahner, God having given the created world a supernatural end entails that the world and the human being must always and everywhere have a “different inward structure”. Cf. Rahner, ‘Über das Verhältnis’, 329. 8 This is not surprising of course, as Rahner studied with Heidegger while he was preparing a doctoral dissertation in philosophy in Freiburg from 1934-1936. 9 Rahner, ‚‘Natur und Gnade’, 219. supernatural is no longer connected to their everyday existence, people are no longer interested in it and choose to focus completely on the natural order.10 3. Toward A New Metaphysics Rahner develops his alternative metaphysical vision by way of a new theological anthropology, partly indebted to ideas of nouvelle théologiens.11 From Maréchal, Rahner takes the understanding of the human person as essentially a spirit with an intellectual transcendental dynamism. In Thomistic terms, human persons have a desiderium naturale visionis beatificae, a natural desire for the vision of God.12 But Rahner also distances himself from the nouvelle théologie, insofar as this movement “naturalises” grace. If the natural desire for God would be constitutive of human nature, then God would owe the beatific vision to humankind created as such. 13 Rahner wants to defend the gratuity of grace. He argues that receiving God’s grace as unexpected wonder is necessary for the human person to be a “real partner” of God. But as a result, his theological anthropology seems to run into a paradox: the “being” of the human person is its ordination to communion with God in love, but this love must be received as a free gift.14 As a solution for this dilemma, Rahner introduces the idea of the “supernatural existential”. The starting point is the conviction that God wants to communicate God’s self to humankind. For this purpose, God creates the world and human beings. But in order to be able to receive God’s gift of love, the human being must have a congeniality for this love. Rahner therefore argues that the human person is created with a “real potency” for grace, a burning desire for God’s love which forms the central and abiding existential of the human person. This “supernatural existential” transforms human nature, enabling encounters with grace in concrete existence.15 Ibid., 213. Amongst others Maurice Blondel, Joseph Maréchal, and Henri de Lubac. Cf. Stephen Duffy, The Dynamics of Grace. Perspectives in Theological Anthropology (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1994), 295-303. 12 Rahner, ‘Natur und Gnade’, 214. 13 Rahner, ‘Über das Verhältnis’, 329-330. Rahner does not refer explicitly to a particular theologian here. He only cites a certain “Anonymous D”, whom he considers a representative of the nouvelle théologie nonetheless. In opposition to this D, Rahner professes himself in agreement with the encyclical Humani Generis which warned against destroying this gratuity: “Others destroy the gratuity of the supernatural order, since God, they say, cannot create intellectual beings without ordering and calling them to the beatific vision.” Cf. Humani Generis, 26. 14 Rahner, ‘Über das Verhältnis’, 330-331. 15 Ibid., 336-339. 10 11 Importantly, Rahner argues that this supernatural existential must be understood itself as a free gift of grace. A closer look at Rahner’s anthropology clarifies this dimension of gratuity. In metaphysical terms, the human person can be described as “spirit in transcendence and freedom”.16 The human person is created as a spiritual being with a natural openness towards “absolute being” or “being in general”. 17 This natural openness is absolutely fulfilled when it receives God’s grace. The nature of the human person therefore can be characterised as potentia obedientialis for the divine life.18 Yet this gift of grace is not required naturally, because according to Rahner, “spirit is already meaningful, without being supernaturally graced”. 19 When God would have chosen to remain silent, human beings would still have had meaningful spiritual lives. Such a human life would be oriented toward a mysterious end that could only be approached asymptotically.20 We could describe it as “pure nature” where human beings have merely a natural end. Rahner’s reflections on the state of pure nature serve to show how the human being is open to grace, yet not naturally entitled to grace. However, the Christian revelation teaches us that: The de facto human nature is not a ‘pure’ nature but a nature in a supernatural order, which man (even as unbeliever or sinner) cannot leave, and a nature, which is continually being determined (…) by supernatural salvific grace that is being offered to it.21 Due to the free gift of the supernatural existential, human persons have a supernatural transcendence that is “opened and borne by grace”. 22 The desiderium naturale which forms the transcendental condition for any spiritual life, has in our concrete order of existence been transformed supernaturally and is therefore “The ‘definition’ of the created spirit is his ‘openness’ to being as such: he is created, inasmuch as he is openness to the fullness of reality; he is spirit, inasmuch as he is openness to reality as such and absolutely.” Rahner, ‘Natur und Gnade’, 231. 17 Rahner thus makes a conceptual distinction between the gratuitousness of God’s creation of the human being with its potentia obedientialis or openness to being on the one hand, and God’s free gift of grace or the supernatural existential to the human being, on the other hand. Rahner, ‘Natur und Gnade’, 225. 18 Rahner, ‘Natur und Gnade’, 235. Clearly, the concept of potentia obedientialis advocated by Rahner is a more dynamic and positive understanding of the concept of potentia obedientialis than the neoScholastic understanding of non-repugnance. 19 Ibid., 234. 20 Rahner, ‘Über das Verhältnis’, 343. 21 Rahner, ‘Natur und Gnade’, 230. 22 Ibid., 225. 16 orientated towards its absolute fulfilment in grace. Our world is a world of grace. 23 Pure nature can therefore only serve as a postulate (Restbegriff) to describe what remains if God had not decided to gift humanity with the supernatural existential. So while in the light of revelation we can make a conceptual distinction, de facto we cannot find nature in a “chemically pure state”. Nature and grace are always dynamically experienced together.24 Such an interpenetration of nature and grace has several important consequences. It leads Rahner for instance to the development of his famous theory of the anonymous Christian.25 In this paper, however, we will focus on the implications for the relationship between philosophy and theology. 4. Philosophy and Theology The relation between philosophy and theology, so Rahner argues, is part of the larger theological question of the relation between nature and grace. Essentially, he argues for both a unity and distinction of philosophy and theology. If nature forms in concrete reality an inner moment within grace, then analogously, philosophy must be understood as an inner moment within theology. To put it in transcendental terms, philosophy forms the “condition for the possibility” of theology.26 While Rahner maintains that theology forms the highest norm of knowledge, he also emphasises that theology requires a philosophical form of knowledge. His argument calls to mind Thomas Aquinas’ teaching gratia non tollit naturam sed perficit (grace does not destroy nature but perfects it).27 In a similar vein, Rahner argues that hearing the word of revelation presupposes an element of thinking, more precisely a transcendental and historical human self-consciousness. So theology requires philosophy.28 But in Rahner’s conception, this philosophy cannot be a pure In the words of Leo O’Donovan, Rahner envisions our reality as a “world of grace”. Cf. Leo O’Donovan, A World of Grace: An Introduction to the Themes and Foundations of Karl Rahner’s Theology (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 1995). 24 Cf. Rahner, ‘Über das Verhältnis’, 340-341. 25 For Rahner’s reflections on the anonymous Christian, cf. Karl Rahner, ‘Das Christentum und die nichtchristlichen Religionen, in Schriften zur Theologie, Band V (Einsiedeln – Zürich – Köln: Benziger Verlag, 1962), and Idem, ‘Über die Heilsbedeutung der nichtchristlichen Religionen’ Schriften zur Theologie. Band XIII (Einsiedeln – Zürich – Köln: Benziger Verlag, 1978). 26 Rahner, ‘Theologie und Philosophie’, in Schriften zur Theologie. Band VI (Einsiedeln – Zürich – Köln: Benziger Verlag), 92-93. 27 Cf. Summa Theologiae, I, 1, 8 ad 2. 28 Rahner, ‘Theologie und Philosophie’, 94. 23 philosophy, given the universal working of grace in our concrete world. 29 “The philosophical man stands in his thinking always under a theological a priori transcendental determination that orientates him towards the immediate presence of God”.30 The very process of philosophising thus involves, by its nature, an element of grace. For this reason, philosophy can be understood as a forerunner of theology, a theology that has not yet arrived at its own nature.31 Importantly, Rahner is careful to point out that this assertion is first and foremost a theological statement.32 Nevertheless, it could be asked whether this endangers the autonomy of philosophy. Rahner is aware of this, and argues that the indispensable ancillae theologiae must be a domina if she is to serve theology properly. Again, the relation between nature and grace provides the relevant background here. Grace as God’s self-communication of God requires an addressee to whom grace is not owed. It requires a spiritual nature (Geistnatur) that is free to accept this offer. Thus, the autonomy of the spirit as “nature” is the transcendental condition for the possibility of grace and revelation.33 Rahner finds support for his argumentation in the teachings of the First Vatican Council. 34 Just as he criticises the sharp distinction between nature and grace, so he also rejects a sharp distinction between knowledge grounded in reason and knowledge grounded in revelation. Dei Filius states that God can be known naturally through the light of reason. This secular knowledge springs from the same root as theology, i.e. God the source of all truth. Rahner reads this as a positive affirmation that “man cannot escape from having to do with God, and even at a stage prior to any Christian revelation conceived of in explicit or institutional terms.”35 Contrary to Blaise Pascal’s distinction between the God of the philosophers and the God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Jesus Christ, the Rahner acknowledges a certain use of the term “pure philosophy”, namely to indicate a “selfclarification of human existence” that does not take “any material contents and norms from the official, socially constituted and hence ecclesiastical, special, thematised revelation”. Cf. ibid., 99. 30 Rahner, ‘Zum heutigen Verhältnis von Philosophie und Theologie’, in Schriften zur Theologie. Band X (Einsiedeln – Zürich – Köln: Benziger Verlag), 71-72. 31 Ibid., 73. 32 Ibid. 33 Rahner, ‘Theologie und Philosophie’, 95-97. Rahner recalls how the “secularisation” of philosophy started already with Thomas Aquinas: “It was Thomas Aquinas who first recognised philosophy as an autonomous discipline, and its secularisation, its emancipation, constitutes the first step in the legitimate process by which the world is allowed to become ‘worldly’, a process which, ultimately speaking, is willed and has been set in motion by Christianity itself. Theology must, of its own nature, will that man shall freely, independently, and on his own responsibility, achieve an understanding of himself. It must will to have philosophy concomitant to, and independent of itself. Only in this way can philosophy be, in any effective sense, a partner to theology.” Cf. Rahner, ‘Zum heutigen’, 86. 34 Especially in the Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith, Dei Filius. Cf. DS 3000-3045. 35 Rahner, ‘Zum heutigen’, 76. 29 Council affirms that the God known by reason is the same God who appears in Christian revelation.36 Since human reason has salvific importance independently from Christianity and Church, autonomous philosophy is vitally important of itself.37 5. Concluding Remarks Do Rahner’s views on theology and philosophy convince? And if so, what are the consequences for contemporary theology? We will address these questions with several closing remarks. First, it could be argued that the autonomy Rahner accords to philosophy remains too weak. Most philosophers would object to being labelled as “forerunner[s] of theology”. In Rahner’s defence, we must repeat that he emphasises that this judgment is theological in nature. It could therefore be read mainly as an exhortation to theologians to engage in genuine encounters with philosophy. Moreover, Rahner does not advocate the usurpation of philosophy by theology, but stresses the importance of an autonomous partner for theology. Secondly, it could be questioned whether the acknowledgment of operative grace outside the Church and theology relativises the role of theology. Rahner does affirm that theology is the “highest form of knowledge” and that theology prevails over philosophy in case of conflicts pertaining to matters of faith.38 Nevertheless, it remains unclear why revealed knowledge is qualitatively different from natural knowledge. Particularly, the role of Jesus Christ as the “full revelation of divine truth” and the related function of the Church are put into question.39 Further research into the Christological and ecclesiological dimensions of Rahner’s ideas is therefore warranted. This leads us to a final observation. Rahner’s dynamic interrelating of nature and grace seems to result in a paradox. On the one hand, his new metaphysical understanding of nature and grace strengthens the plausibility of Christian faith, bringing the experience of grace closer to human existence in the world as a whole. On the other hand, the resulting openness for the secular world also confuses the role of Christian faith. Rahner himself admits this, stating that “the relation between Ibid. As Joseph Fritz remarks, Rahner’s interpretation of the First Vatican Council is somewhat unusual. He seems to recognise in this Council an openness to the secular world that many others see only in the Second Vatican Council. Cf. Peter Joseph Fritz, ‘Karl Rahner Repeated in Jean-Luc Marion?, Theological Studies 73 (2012): 330. 38 Rahner, ‘Zum heutigen’, 77. 39 Cf. Declaration ‘Dominus Iesus’ on the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church, Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, 2000. 36 37 philosophy and theology, is in itself extremely obscure and complex”.40 But he also mentions our time is a time of pilgrimage. We must come to terms with the reality of pluralism and with the inability to achieve an integrity that would overcome this plurality.41 So theologians, in all their limitations, should strive to further insight into the various ways in which God’s grace affects our world. In view of this, we would propose to bring Rahner’s ideas in dialogue with John Paul II’s encyclical, Fides et Ratio. This encyclical could be read as taking contemporary philosophy insufficiently serious.42 Here Rahner’s reflections could provide a reading key of this encyclical that prevents a too simple subordination or rejection of contemporary philosophy. Yet the encyclical’s emphasis on the importance and distinctiveness of the Christian faith tradition also provides a strong counter narrative against a relativisation of Christian faith and could therefore augment and complement Rahner’s argumentation. Thus, bringing Rahner and Fides et Ratio into dialogue seems a promising way to continue reflecting on the relation between philosophy and theology. Rahner, ‘Zum heutigen’, 75. Ibid.,78. Rahner uses the terminology “gnoseological concupiscence” here. 42 For a commentary on Fides et Ratio that discusses two distinct reading trajectories of this document, cf. Lieven Boeve, “The Swan or the Dove. Two Keys for Reading Fides et Ratio,” Philosophy and Theology 12, no. 1 (2000): 3-24. 40 41 “NATIVE ATTUNEMENT TO GOD”— FRANS JOZEF VAN BEECK 1. The basis for a new Theological Synthesis. Trichotomy: Cosmology – Anthropology – Theology The following reflections will consider at large the late Dutch Jesuit systematic theologian, Frans Jozef van Beeck (†2011) and certain foundational elements of his theological synthesis from his incomplete, magnum opus, God Encountered43. A synthesis, which for van Beeck reflects a profound sense of unity, both between the various theological disciplines in relation to Tradition, as well as the equally profound cosmological-anthropological-theological unity underlying his work. A helpful entry point into his theological synthesis involves gauging his specific, theological anthropology as a dynamic, “native attunement to God”. Generously resourcing from Tradition and with an eye towards the contemporary world, van Beeck situates his theo-anthropology by reinterpreting the traditional premodern trichotomy of bodysoul-spirit in terms of cosmology (body), anthropology (soul) and theology (spirit). Clarifying the central importance of this reinterpretation, van Beeck states: It has been repeated again and again in this systematic theology that humanity is ultimately what it is by virtue of the dynamic orientation to God that lies at the core of its being—that is to say, by virtue of final causality. It is true, of course, that humanity remains essentially marked by cosmic heteronomy and by anthropological—that is, distinctively spiritual—autonomy. Yet in the last analysis humanity is essentially and decisively marked by theonomy. Created and sustained by God in everything we are and have and do, we are natively aimed at God.44 Van Beeck employs this trichotomy in order to account for the very dynamism of humanity’s potentia obedientialis and desirous, thenomous attunement to God. Van Beeck’s approach to Revelation, featuring native attunement, exhibits a dynamic, “anthropological infrastructure”, which is especially evident in the “mystical form of faith” wherein the transition from nature to grace “meet in perfect harmony, as See Frans Josef van Beeck, S.J., God Encountered: A Contemporary Catholic Systematic Theology, Volume 1: Understanding the Christian Faith (San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row, 1989). See also Frans Jozef van Beeck, S.J., God Encountered: A Contemporary Catholic Systematic Theology, Volumes II/I-II/IVB (Collegeville, MN.: The Liturgical Press, 1993-2001); henceforth: GE. 44 van Beeck, GE, §141, 5, 8. 43 humanity truly comes into its own, on the strength of total dependence of God.”45 For van Beeck, theonomy is of a fundamental, natural orientation, one that shows “a new relational self...their deepest identity, filled to overflowing, [which] turns out to have an ability that they barely, if at all suspected: the capacity for total abandon of self.”46 And it is this capacity for ecstasy, or de-centering, which van Beeck interprets as both our potentia obedientialis to God as well as the “person’s deepest identity”, which in a participative encounter, van Beeck will himself define as “mysticism”.47 Mysticism, in this sense, is itself “natively” rooted in a fundamental, theological anthropology, which in turn, by way of the tradition of Christian humanism, is nourished by a continual vision of man as fundamentally relational, showing human integrity, fulfillment and solidarity with others by way of furthering our union with God. (I will return to this point in the conclusion). Such a native attunement, an “integrated account of the cosmos, humanity, and God," van Beeck argues, "has animated the Great Tradition of the undivided Church.”48 Concerning the task of systematic theology, van Beeck portrays this unity as something that seeks to be achieved anew, and yet it stems from the very givenness of creation itself; this is not reducible to Romantic optimism, however. Van Beeck argues that ‘unity’ and native attunement emerge as a dynamic pairing of "gratuitousness" and "reciprocity", which amounts to asking what is at stake in “economy” and theology? For van Beeck, it is nothing less than the “admirable exchange” [admirabile commercium].49 For such a reciprocal exchange both epitomizes and preserves the crucial linkage between doxology and soteriology, between the divine exitus and humanity’s and the world’s graced reditus. While economy here stands for reditus, it is one fundamentally of reception and participation, yet founded upon a clear asymmetry, in so far as the Van Beeck, GE, §84, 1, b, 198-9. Ibid. 47 Ibid. 48 Van Beeck, “Trinitarian Theology as Participation”, 307. 49 From the Antiphon at Vespers, January 1, Feast of the Holy Mother of God: “O admirabile commercium! /Creator generis humani/ animatum corpus sumens/ de Virgine nasci dignatus est:/ et procedens homo sine semine/ largitus est nobis suam deitatem.” [“What admirabile exchange! / Humanikind’s Creator/ taking on body and soul/ in his kindness, is born from the Virgin:/and, coming forth as man, yet not from man’s seed/ he has lavished upon us his divinity.”] With that said, I would like to furthermore publically recognize and thank Prof. Rik van Nieuwenhove, with whom I have had a series of “admirable exchanges”, having directed me to the work of Frans Jozef van Beeck, S.J. 45 46 natural order and the order of grace are governed by the dynamics of an encounter that is divinely initiated—of a partnership that is entirely of God’s making.....The account of God’s exitus—the central profession of faith—must, therefore, be considered the foundation of Christian faith, and consequently the standard against which all other doctrines are to be measured.50 Here, the dogmatic content of Christian faith—Creed, Councils, the Church’s magisterium—is normative and asymmetrically asserted. And yet, van Beeck will also stress that such an exitus and asymmetry is not to be understood in a linear progression, yet as mutually related with the act of creation itself and its “native attunement” to such exitus. The interpretation of grace and nature is seen here as mutual and dynamic. Or, in terms of analogy: a greater preference for univocity in its stress of immanence over and against equivocity, while clearly reaffirming God’s greater dissimilutdo precisely in terms of semper maior. Van Beeck clearly refuses a two-tiered structure, such that the “orders of grace and nature are intertwined, not juxtaposed.”51 This relationship is thus perichoretic, though because of the prior asymmetry of the exitus as the normative content of Christian faith, the intertwining and mutuality of nature and grace are placed in the dynamic tension of mutuality and asymmetry. Here, Incarnation neither “replaced [n]or overwhelmed” creation’s integrity, yet enhances it to “rediscover, at the heart of the order of creation, its prior, native openness to the order of the incarnation”.52 Hence, such an emphasis upon creation’s native attunement to God, not only as mutual, but also intrinsic to the asymmetry of the divine exitus, is the opening for the necessity of fundamental theology. 2. Van Beeck on the role and identity of Fundamental Theology today The mediating function of van Beeck’s theological anthropology and its dynamic immanence between the orders of nature and grace, highlights the importance of such mediation in terms of fundamental theology. Native attunement, van Beeck reminds us, as a movement from particularity to universality, precisely involves a fundamental theology that demands for “integrity” in such a move.53 Likewise, the Van Beeck, GE, §57,3,a, 23-4. Van Beeck, GE, §57,3,d, 25. 52 Ibid. 53 See van Beeck, GE, §91, 3-4, 260-262. 50 51 mediation of native attunement, from universality to particularity is similarly upheld, in that such a “universalist orientation...is not available apart from some positive form of commitment or faith.”54 With this economic two-way exchange in mind, a more distinctly radical hermeneutics55would undoubtedly be highly critical of van Beeck’s thinking of unity. Unity, from this vantage point, is construed as a form of ontological enclosure and a reduction of difference to a closed, hegemonic narrative in its privilege of unity as primary. Hence, postmodernity’s engagement with contemporary culture resorts to a more descriptive, de facto recognition, one which “casts doubt on the very possibility of any unified understanding of the world and humanity.” 56 Here, the prospect of “unity” is gauged as a modern, human achievement, under the banner of “progress”. Against this modern, technological and socio-economic argument, one which does not purport to leave the realm of description in its culture hermeneutics, unity is seen as idealistic and implausible. Here, theologically speaking—and it is important to bear this in mind— it is not a matter of whether or not claims of unity are credible or accountable, with reference to primary sources of theological reflection and discourse. Rather, the critique is made with reference to plausibility and a certain foundational ratification and legitimation of a credibility-gap, as now fundamental in its cultural hermeneutical description. By shifting the theological terrain away from the task of credibility and/or accountability to that of cultural plausibility, such shifts lead to the adoption of a critical fundamental theological approach, which in part sees theology’s apologetical dimensions as situated within and oriented towards the radically secular, postChristian cultural milieu.57 However, in terms of unity, there is a profound risk in rejecting the claims of a perichoretic or differentiated unity—both intrinsically, within the practice of theology itself, as well as its continual reemergence within both Van Beeck, GE, §91, 3, 260. Radical hermeneutics is understood here in light of postmodernity’s affirmation of différence, contingency and its theological reaffirmation of grace and gift as adventitious and extrinisc 55—amid a Derridean posture of hospitality to pure alterity. See generally Robyn Horner, Rethinking God as Gift: Marrion, Derrida, and the Limits of Phenomenology (New York: Fordham University Press, 2001). 56 Van Beeck, GE, §92, 2, 266. 57 In Leuven, we know this approach quite well as the hermeneutical-contextual theological approach. And as the praxis of theology should always attend to its embodied, concrete, Incarnational rootedness, the emphasis upon such a contextual approach is not only the distinguishing hallmark of current theology within Leuven, but is its very strength. 54 55 religion and culture—by the gradual, habitual substitution of the de facto credibilitygap of its cultural hermeneutics for a more fundamental, de jure divorce between Creator and the creaturely itself. Here, whether it is a resignation towards, or the celebration of difference and multiplicity, recognizing the contextuality of theology shifts its contemporary imperatives away from the transformative demands of an ever-new unity and synthesis, and instead, steers it towards the description of plausibility. Here, one runs the grave risk of losing a taste for unity and the inexhaustible participation within the “admirable exchange”. This is especially the case, van Beeck argues, “in the universities, where theology most keenly experiences the pressure to adopt a truly scholarly (i.e. neutral, critical, skeptical) stance.” 58 By this, van Beeck at first charges such a scholarly, independent, fundamental theology as guided not so much by its Tradition hermeneutics as by its self-reflexive, critical attitude, which of itself is an important, yet insufficient guide. In turn, van Beeck is keenly aware and critical of fundamental theology’s purported autonomy in relation to other theological disciplines. With reference to David Tracy, such a problematic autonomy, for van Beeck is precisely the way in which various “publics” of Church, academy and society are constructed as formally separate, such that fundamental theology is called to recognize and mediate between each of these in our contemporary, post-modern, pluralistic context. Contrary to this contextual departure, van Beeck recognizes that native attunement itself fundamentally mediates the theological and cultural in a “direct encounter”, one which is always open to new expressions of unity between religion and the contemporary world. 59 This direct encounter is then analogously applied whereby van Beeck recalls the “classic Catholic configuration” in equally placing dogmatic and fundamental theology in a direct relationship. Following from this direct encounter, he thereby argues that it’s a matter of concrete “discernment...to determine if the need for a configurative balance between Church and culture demand[s] more emphasis upon fundamental or dogmatic theology.”60 Once again, this appeal to “discernment” is made within view of a concrete, embodied cultural hermeneutics that participates in this direct encounter and is ultimately open to cultural transformation, rather than primarily being one of adaptability, accommodation and neutral description. From Van Beeck, GE, §92, 4, 267. See van Beeck, GE, §92, 5, 269. 60 Van Beeck, GE, §92, 5, [m], 270. 58 59 this prerogative, van Beeck charges that fundamental theology today often too easily invests criticism with a near formal authority, which “in an autonomous, unbiased fashion...adjudicate[s] the claims of both faith and culture.”61 Admittedly, the strength of this approach in positioning theology as a mediator of distinct, yet related publics is that it takes secularization and pluralism seriously, “empathetic to the credibility gap that de facto separates faith from culture and hence, doctrinal theology from fundamental theology.”62 However—and this is indeed a strength in van Beeck’s critique—not only is this credibility gap empathetically recognized, but also (and problematically), when viewed from a perspective of unity and direct encounter between faith and culture, becomes ratified and legitimated as such. Under the idiom of “dialogue” between these contextually divided publics, such a ratified gap, de jure, increasingly appears in its hermeneutical engagement as a latent return of “extrinsicism” and further polarization. With this heavy critique, van Beeck claims that such trends within much of current fundamental theology depict a view of the world and humanity as intrinsically separate and distinct from God. And by privileging the primacy of critical reflection, these trends result in “control[ing] the encounter”, unflinching in its gaze towards the academy and thus, maintain its neutrality as an “arbitrator” and not as a “mediating participant...between grace and nature without sharing in either.”63 Arising from this reading of current trends within fundamental theology as separate and autonomous, van Beeck extends this critique in noting that while critical reflection is absolutely necessary to “purify positive faith and thus deepen it”, it can by no means, however, “generate any positive faith itself.”64 Rather, positive faith alone can give meaning and purpose to critical reflection, without which criticism alone cannot justify itself. For, as van Beeck very wisely points out, given the insistence of separating such disciplines, “it is notoriously hard to pass from critical reflection to positive theology.”65 Instead, for van Beeck, such difficulty shows both an asymmetry and primacy to positive faith—inseparably intertwined with a dynamic Van Beeck, GE, §92, 5, 270. Ibid. 63 Van Beeck, GE, §92, 5, 271. 64 Van Beeck, GE, §92, 6, 271. 65 Ibid. 61 62 fundamental theology—and what positive faith alone can provide: “the account of the actual life of grace experienced in positive Christian worship, life and teaching.”66 To conclude, the wealth of van Beeck’s theological synthesis and the dynamic immanence of his ‘native attunement’ allows for us to better heed the compelling injunctive put forth by Louis Dupré. Writing in the forward to the revised translation of Henri De Lubac’s famous Surnaturel, Dupré rightly calls upon the great Brabantine mystical theologian, Jan van Ruusbroec, stating that “Spiritual writers…who wrote in the tradition of Ruysbroeck, held out for an unmitigated version of the desire of God as God is in himself.”67 Which, by way of continual ressourcement, “[T]heology must once again become spiritual. The spiritual attitude excludes a break between nature and grace. Embracing all of life, yet in a receptive attitude, it is at once more worldly and more deeply steeped in grace.”68 Hence, “spiritual” theology here means a praxis-oriented discourse committed to thinking through the profound repercussions of both cosmological and anthropological orders as natively attuned to God, while in turn upholding this natural relationship as a furthering of their respective autonomy, particularity and immanence amid such a theonomous relation. Thus for van Beeck, the question becomes whether or not contemporary theology, in proceeding from such a native attunement, is indeed relearning how to be spiritual? Van Beeck, GE, §92, 6, 272. See Louis Dupré, “Introduction”, Henri De Lubac, S.J. Augustianism and Modern Theology, trans. Lancelot Sheppard (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 2000), xiv-xv. 68 Ibid. 66 67