Struggling Readers-Literature Review

advertisement

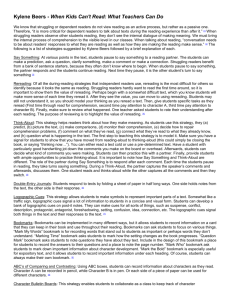

Struggling Readers Literature Review Melissa Philyaw Appalachian State University RE 5730 04-11-2013 Teachers have many theories about why struggling readers exist. In my research, I have uncovered four sources that seem to agree and disagree with each other about struggling readers. I have discovered that all four sources have some common themes that run throughout the articles. These themes are: word study, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and motivation. Although struggling readers exist at any age, this paper will primarily focus on struggling adolescent readers. One of the common themes in the research that I completed is word study. By definition, word study involves breaking words into word parts such as breaking words into syllables and decoding multisyllabic words. According to Newman, Wexler, and Wexler, teachers need to focus on word attack strategies. For example, students can “attack” the word replace by dividing it into an open syllable (re), which keeps the ling vowel sound, followed by a vowelconsonant-e syllable type (place). Students benefit from improved knowledge of word meanings and concepts (Boardman, Roberts, Vaughn, Wexler, Murray, and Kosanovich). Older students who are deficient in decoding and word analysis skills require instruction in word study. Teachers must be able to allocate time and resources to provide appropriate interventions to these students (Boardman, et al.). In short, students benefit more from reading instruction when they know the meanings of words and how to break them apart. The second common theme in my research is in the area of fluency. Fluency is defined as smoothness or flow with sounds, syllables, words and phrases joined together when speaking quickly (Wikipedia). As a teacher, I know that a good reader is a fluent reader. Fluency takes time to perfect. It takes knowledge of sight words and decoding skills. Fluency is important in word reading and in comprehension. Adolescent readers struggling with fluency, students should receive repeated opportunities to practice fluent reading orally with feedback from a more proficient reader- either a teacher or a peer (Boardman, et al.). To be considered a fluent reader, older struggling readers must be able to read text at a minimum of 100 words per minute with five or fewer errors (Newman, et al.). Strategies that help struggling readers read more fluently are: repeated readings, higher order thinking skills such as comparing and contrasting, summarizing, discussing cause and effect, inferring, and self monitoring (National Teacher Education Journal). The third theme in my research is in the area of vocabulary. The articles agree that inadequate vocabulary is a major concern for struggling adolescent readers. When students understand the meanings of the words they encounter in text and have strategies to figure out unknown words, they are more likely to understand the content of what they are reading (Boardman et al.). To help students acquire a more extensive vocabulary, teachers are encouraged to use semantic maps, use tier 2 and tier 3 words. To acquire content specific vocabulary, teachers must teach students to use keywords, mnemonics, and elaborative techniques (Newman et al.). Other vocabulary acquisition strategies for students include: listing related words together, using context clues to elicit word meaning, and feature analysis that allows students to categorize words to reinforce word meaning (National Teacher Education Journal). Basically, help kids learn how to figure out what words mean based on breaking words apart, grouping similar words together, and use context clues. The next overarching theme in my research is comprehension. Comprehension is defined by Wikipedia as the level of understanding of a text or a message. This understanding comes from the interaction between the words that are written and how they trigger knowledge outside the text or message. Struggling adolescent readers may have difficulty in constructing meaning from the text. Teachers should teach before, during, and after reading strategies to move students toward becoming independent learners (Newman et al.). Teachers should activate prior knowledge, use graphic organizers, teach comprehension monitoring strategies, teach summarization skills, teach students to ask and answer questions, and use multi-component strategy instruction (Boardman et al.). Teachers can use a wide variety of activities to support the struggling adolescent reader who is lacking in comprehension. Such strategies include: questioning the text, KWL charts, Think Aloud, directed reading activities, and anticipation guides (National Teacher Education Journal). In summary, provide scaffolding support for struggling readers that lack adequate comprehension skills by modeling these strategies in the classroom. The last overarching theme in my research is motivation. Adolescent struggling readers often lack the motivation to read. This impairs their comprehension and limits their ability to develop effective reading strategies or to learn from what they read (Boardman et al.). Teachers should make preferred reading materials available to students. This will increase the amount of time and effort students are willing to spend engaged with text (Newman, et al.). Students are motivated by reading materials that are of interest to them. Students are also motivated by using technology. Incorporating technology has been proven useful to enhance/support reading skills, because students respond to technology and are constantly engaged with it (National Teacher Education Journal). Often, adolescents’ curiosities are not addressed in trade books, and so alternative materials such as magazines, newspapers, and the Internet are essential resources (Ivey, G.). In summary, students will be more motivated when the content is relevant and accessible to them. Moreover, when technology is used, struggling readers are more likely to be engaged in the lesson. In conclusion, all four articles identified the areas of word study, fluency, inadequate vocabulary, comprehension, and motivation as areas in which adolescent readers may have difficulty. Not all struggling reader exhibit deficits in every area. Some have deficits in only one area while others struggle in multiple areas. Teachers must be skilled professionals who use their assessments to drive instruction to create individualized lessons for their students. Teachers must use meaningful strategies that help students in their specific area of difficulty. In my opinion, I feel that the greatest area of need is in the area of motivation. If a student is unmotivated and not engaged in the lesson, all is lost. I feel teachers are responsible for sustaining student motivation daily. Students who are motivated will try their best even when they feel like giving up. Bibliography Boardman, A. G., Roberts, G., Vaughn, S., Wexler, J., Murray, C. S., & Kosanovich, M. (2008). Effective instruction for adolescent struggling readers: A practice brief. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction Ivey, G. (2009). Intervening when older youth struggle with reading. In K.A. Hinkchman, & H.K. Sheridan-Thomas, (Eds.), Best practices in adolescent literacy instruction. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. National Teacher Education Journal, Volume 5, Number 2. Spring 2012. Thomas, Cathy Newman, & Wexler, Jade (2007). 10 Ways to Teach and Support Struggling Adolescent Readers. Kappa Delta Pi Record