A.O.2

advertisement

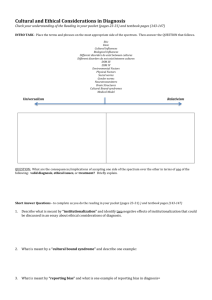

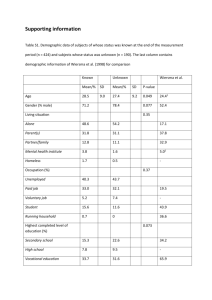

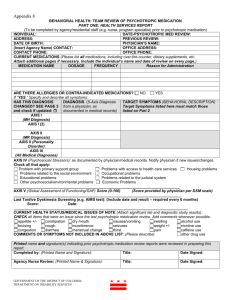

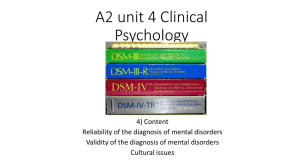

Diagnosing abnormal behaviour This document contains: DSM and ICD – basics. Diagnosis o Assessment o Issues in classification and diagnosis Validity Reliability Cultural issues Ethical issues DSM IV – classification system – classroom notes (based on Course Companion) Kraepelin developed the first comprehensive classification system for mental disorders, believing that they could be diagnosed from observable symptoms, just like physical illness. DSM IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder” + ICD 10 (Internatioanl Classification of Diseases) Differences; different headings, different names at times. ICD – more likely to indicate causes rather than purely sumptoms. Revised many times DSM – composed of several axis: Axis 1 – Clinical symptoms (eg. Catatonic schizophrenia) Axis 2 – Developmental and personality disorders (additional diagnostic classifications that may contribute to an understanding of the Axis 1 syndrome) Axis 3 – Medical conditions (physical problems relevant to the mental disorder) Axis 4 – All potentially stressful events (loss of job, divorce), enduring circumstances (poverty) that might be relevant to the disorders are rated on a scale ranging from 1 (none) to 6 (catastrophic) for the past year. Axis 5 Global assessment of functioning 1-9 social, occupational and psychological functioning is rated (during last year). So, a person might be suffering from depression (Axis 1) but on top of that he has occasional panic attacks (Axis 2) and is shy, verging on social phobia (Axis 2). He has no contributing medical conditions (Axis 3), but has recently lost his sister in a terrible accident (Axis 4) and his parents are divorced and not talking since the accident (Axis 4). He goes to school on regular basis but has no friends (Axis 5). Look at Mini DSM (Swedish copy) Diagnosis 1. Therapists tries to collect as much information as possible about a person. This is called Assessment. The goal is to compile idiographic information (individual) about the person (idiographic vs. nomothetic-general info). This would include causes and probable course of her present dysfunction and suggest what kind of strategies would help her. “To help a particular person the practitioner must have the fullest possible understanding of that person” (Tucker, 1998). What kind of assessment is used depends on the theoretical background of the practitioner. 2. Diagnosis, very often using a classification system like DSM IV 3. Treatment, drug-treatment, CBT, Psychoanalysis, group therapy… also depends on the practitioner’s theoretical background. CLINICAL ASSESSMENT Each practitioner has their way of doing this, but most assessments can be divided into the following categories: - Clinical interviews - Tests - Observations Each of these needs to be standardized (common steps exist), reliability (refers to the consistency of the test, we have test-retest reliability and inter-rater reliability), validity (it must accurately measure what it is supposed to measure. Here we have face validity – how valid it is by first sight. Eg. If a depression test contain a question about how often a person cry, this might seem like a valid question, but it really doesn’t give an accurate picture of depression. We also have predictive validity). Clinical interviews Very widely used by must practitioners. Problems: - Validity and reliability issues - The client gives false reports/are unable to give accurate reports - Interviewer bias (race, sex, age). Tests Eg. Projective tests (like Rorschack, TAT, intelligence tests, neurophysical tests) + can reveal subtle information - difficult to get standardized, reliable, valid measures Personal inventories (problems with culture and validity problems) Issues in Diagnosis and Classification: Problems with assessment interviews (CC p. 140) But also(collected by Kleinmutz (1967) that there are limitations to the interview process: Information exchange may be blocked if either the patient or the clinician fails to respect the other, or if the other is not feeling well. Intense anxiety or preoccupation on the part of the patient may affect the process. A clinician’s unique style, degree of experience, and the theoretical orientation will definitely affect the interview. Reliability= this is high when different psychiatrists agree on a patient’s diagnosis when using the same diagnostic system. This is also known as inter-rate reliability. Reliability can be questioned. Despite using the same diagnostic manual psychiatrists end up with different diagnosis. Famous studies: o Rosenhan (1973). A teaching hospital was told to expect pseudopatients – not a single one ventured near the hospital but 41 genuine patients were suspected to be fake. Conclusion: it was not possible to distinguish between sane and insane in psychiatric hospital. o Beck (1962) Agreement on diagnosis for 153 patients between two psychiatrists was only 54% o Cooper (1972) New York psychiatrist were twice as likely to diagnose schizophrenia than London psychiatrists. Result of this: new versions of DSM IV, local variants (eg. The Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital in London 0.88 reliability (should be compared with 64% agreement between raters) Validity: this is the extent to which the diagnosis is accurate. This is much more difficult to assess in psychological disorders, for example because some symptoms may appear in different disorders. Lack of validity is most often due to bias in diagnosis. Bias in diagnosis – how the diagnosis might be influenced by the attitude and prejudices of the psychiatrist or the diagnostic test itself: o Racial o Gender bias o Misconception of the nature of mental states. o Expectation of clinicians. o Over pathologization Ethics Labelling – ethics. What do different classifications lead to: o Sheff – summarized labelling effects (1966) Self-fulfilling prophecy – start behaving the disorder – as they believe they are expected to leading to an increase in symptoms. Distortion of behaviour/confirmation bias (clinicians tendency to have expectations about the person who consults them) – misinterpreting the patient’s behaviour to support assessment. Rosenhan’s (1973) famous study showed that it was difficult to convince staff that the admitted really was just faking their disorder. All behaviour was perceived as being a symptom. Langer and Abelson (1974) – social perception (p. 143 in CC – same man filmed but one condition was that he was a patient – the other that he was a work applicant. Judged completely differently (attractive, conventional looking vs. tight, defensive, dependent) Farina 1980 – natural experiment. One member of a pair of male college students was falsely led to believe the other had been a mental patient – was perceived to be inadequate, incompetent and not likeable Racial/Prejudice (eg.). Gender in the study by Jenkins-Hall and Sacco involving European American therapists evaluating female patients, their rated the African American woman more negatively than the European white one. Institutionalisation: Lack of normal interaction Powerlessness and depersonalisation Dependency Szasz “Idiology and Insanity” (1974 – argued that the use of labels such as mentally ill, criminal or foreigner excluded people. People who are different are stigmatized. Schizophrenic vs. an individual with schizophrenia. Cultural considerations in diagnosis: Culture bound syndromes: though many disorders appear to be universal – that is, present in all cultures – some abnormalities, or disorders are thought to be culturally specific. Eg. Shenjing shuairuo – a disorder only listed in the Chines Classification of Mental Disorders but not included in DSM IV even though it accounts for over half of psychiatric outpatients in China (combination of mood and anxiety). Discussion about this? Should this be listed in DSM IV as well? Do patient start acting the additional symptoms just because it is listed (labelling?). What does it say about our classification system that these are not listed? Some common disorders are not seen in other cultures. Depression in Asia for example – why? Proposed that social support + doctors take care of physical problems. = reporting bias. Eg. India – mentally ill people are cursed and looked down on. China – the same (but the greatest problems are labelled – the rest are ignored). Real cultural differences? Marsella (2003) – differences between symptoms in collectivistic and individualistic countries. Individualistic societies take more affective (emotional) forms (loneliness and isolation), while collectivistic societies take a more somatic (physiological ) form (headaches). Marsella means that it is impossible to compare depression cross-culturally – because it is experienced so differently. Culture blindness – the problem of identifying symptoms of a psychological disorder if theya re not the norm in the clinician’s own culture i.e. seeing the white population as the norm. Eg. In some cultures hearing and seeing a diseased is seen as normal when mourning. How to avoid it (cultural bias)= Learn about the culture of the person being assessed. Evaluation of belingual patients should be undertaken in both languages. Diagnostic procedures should be modified to ensure that the person understands the requirements of the task.