Jason Adams and Ryan Kinsella

advertisement

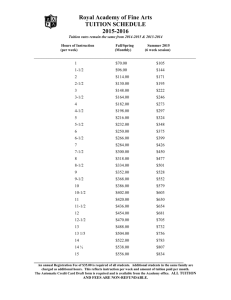

1 Memorandum To: From: Re: Date: Washington Higher Education Coordinating Board Jason Adams, Ryan Kinsella, Analysts Comparative Analysis of State Tuition Pricing December 14, 2009 Executive Summary The following study considers the correlation between the annual percent increase in state tuition pricing for undergraduate resident students and a variety of other factors, including the type of tuition policy, other institutional factors and other economic conditions within a state. We pose this question: what is the correlation between a state's tuition policy and the price of tuition? Following the findings of previous research, we control for other economic and institutional factors and then consider how other explanatory variables correlate with tuition change. Specifically, we consider the following factors: the previous year’s change in tuition, public and private enrollment, state population, bachelor degree production, state financial aid, tax revenues and appropriations for higher education. Comparing these factors of each state across a 10-year period (1998-2008), we aim to identify which of these factors significantly correlate with changes tuition pricing. This analysis used a custom data set comprised of education data collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (administered by the U.S. Department of Education) and the State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO) and demographic and economic data from the U.S. Census Bureau from 1998 to 2008. In addition to tuition analyzing tuition policy and tuition-setting authorities, we include other economic and institutional factors that influence tuition prices. To conduct our analysis, we used five statistical models, including three OLS regressions, a fixed-effects and multilevel model. Through our descriptive statistic and regression analysis, we came to following key conclusions: Tuition policies and the type of tuition-setting authorities are not correlated with the change in the price of tuition Previous year’s tuition change and appropriation change are inversely correlated with tuition change Region and tuition change are not correlated, despite the findings of previous studies An increase in state tax revenue are positively correlated with tuition increase Tuition prices continue to rise across all states, and as a result, interest in tuition policy and factors that influence tuition pricing continue to grow. An understanding of the factors that drive the increases in tuition, particularly during recessionary periods, will inform state policy-makers of the types of conditions that likely affect tuition pricing. Moreover, state universities and colleges will benefit from this type of tuition analysis in terms of future financial planning. 2 Study Background and Purpose During periods following economic recessions and periods when state support was less than inflation and enrollment growth, the rate of net tuition increased significantly.1 Essentially, when states reduce funding due to recessionary impacts, universities and colleges seemingly increase tuition to meet operating costs.2 Regardless of the type of tuition policy, the combination of state support and tuition remains the primary source of revenue for instructional costs.3 On average, 40% of colleges' and universities' revenue come from net tuition, with the remainder of revenue coming from the state and other sources.4 Research also indicates that the annual increase in tuition is greater than the annual increase in spending per student at public institutions across the country.5 Moreover, public universities are using tuition dollars increasingly more to fund other aspects of their institutions (such as research, student services, capital projects). For example, tuition increased by an average of 29.8% between 2002 and 2006 at public research universities across the nation; expenses related to educating students increased by 2.5%.6 Regardless of tuition policy, over the past 20 years, all states continue to appropriate a smaller portion funding for post-secondary education. As a result, tuition prices continue to increase at rates substantially greater than inflation and operating costs. Tuition Policies Not all states have tuition policies. In general, however, 28 states have either formal or informal tuition policies that are articulated in state statute, constitution or in the internal policies of an agency/coordinating board. In contrast, nine states have no single, formal tuition philosophy at the state level.7 The remaining states have policies that depend upon sector or the individual intuitions. Moreover, each state’s tuition policy differs, but many policies share similar characteristics in terms of the authority of who sets tuition, the philosophy behind the policy and the general financing structure for the state and universities. Groups of states are similar in terms of who oversees the tuition policy (e.g., legislature, governing board, etc.), the philosophy behind the policy (low, moderate and high), and state financing structure. However, no two states are comparable across all three of these aspects. Rather than policy alone, state appropriations, tax revenues, economic conditions, other characteristics of the state and a variety of other factors influence what a resident undergraduate pays to attend college. Initial Literature Review Previous studies asked questions similar to our research, focusing on different elements that shape tuition pricing in each state, creating an extensive base of relevant literature on this subject. For our analysis we used the findings of two studies to shape our research questions and improve upon our method and model. Specifically, we reviewed research by James Hearn Carolyn Griswold and Ginger Marine in their paper Region, Resource, and Reason: A Contextual Analysis of State Tuition and Student Aid Policies, and also 1 SHEEO, State Higher Education Finance FY 2008, p. 17. SHEEO, State Higher Education Finance FY 2008, p. 19. State Higher Education Executive Officers. State Tuition, Fees and Financial Assistance Policies for Public Colleges and Universities, 2005-06. November 2006.www.sheeo.org, p. 19. 4 SHEEO, State Higher Education Finance FY 2008, p. 19. 5 Delta Cost Project. Trends in College Spending. 2009, Delta Project on Postsecondary Education Costs, Productivity and Accountability. www.deltacostproject.org, p. 25 6 Delta, 26. 7 Alabama, Delaware, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington. 2 3 3 Jung-cheol Shin and Milton Sande in their paper Rethinking Tuition Effects on Enrollment in Public FourYear Colleges and Universities. Here are some of the findings of previous researched that shaped our analysis: Economic Factors Shin and Sande (1996) find that the state’s economic climate, including job market and government budgetary restraints, are more likely to affect enrollment, graduation rates and the price of tuition more than the state’s tuition policy.8 For instance, tuition prices reflect how much students, or the higher education “market”, is willing to pay for bachelor degree. Additionally, the differences in institutional operating costs and state appropriations also influence how much universities decide to charge students. Region Shin and Sande specifically examined the relationship between tuition (or “financing”) policy and region. The study found that region and the price of tuition are closely related, where Northeastern and Midwestern states generally have higher tuition prices and southern states have lower tuition prices.9 This finding suggests that regions serve as a proxy for other geographic factors, such as social values, norms, attitudes and expectations. In terms of financial aid, larger states tended to award more aid per capita, and the northeast region provided more financial aid funding than the southeast and southwest.10 Tuition-Setting Authority The study also found a strong correlation between tuition prices and the authority that sets tuition prices. Specifically, states in which multi-university boards or state agencies set tuition generally have higher tuition prices.11 States with a greater number of private universities also tended to have higher tuition prices, suggesting that the regional market affects tuition. As a result, we include a variable to account for the effects of private institutions within the state in our analysis. Tuition Policy Both studies indicate that a state’s tuition policy does not have a statistically significant affect on enrollment, degree production or state appropriations. While tuition policy provides some insight into the performance of state institutions, a state's tuition policy only partially explains any changes in enrollment, institutional revenues and net tuition price. These outcomes are also influenced by changes in the local economies, state and federal appropriations, institutional policy changes, historical costs trends within the state, and innumerable other social factors. The two studies support the types of factors included in our study. Our analysis considers the correlation between the annual percent increase in state tuition pricing and a various other factors, including the type of tuition policy adopted by the state and other economic conditions within the state. In general, however, our explanatory variables can be characterized into two types: formal, institutional factors that influence tuition prices and other market (or economic) factors that influence tuition pricing. 8 Shin, Jung-cheol, Sande Milton, "Rethinking Tuition Effects on Enrollment in Public Four-Year Colleges and Universities," The Review of Higher Education, 2006, 29, 2, pp.213-237. 9 Hearn, Griswold and Marine, p. 256. 10 Hearn, Griswold and Marine, p. 264. 11 Hearn, Griswold and Marine, p. 262. 4 Project Data This analysis used a custom data set comprised of education data collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (administered by the U.S. Department of Education) and the State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO) and demographic and economic data from the U.S. Census Bureau from 1998 to 2008. Where footnoted, SHEEO adjusts state tuition amounts for the cost of living. To arrive at constant dollar figures, adjustment factors include Cost of Living Adjustment, Enrollment Mix Index and Higher Education Cost Adjustment Tuition. To characterize the types of tuition policy in each state, our analysis uses data compiled by the State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO) and published in their report, “Survey of State Tuition, Fees, and Financial Assistance Policies” (2005). The survey asks executive leaders in each state’s higher education community to characterize their state’s tuition and financial aid policies. In our analysis, we use the survey to identify the tuition philosophy of each state (low, medium, high, informal or other), in which a “low” tuition philosophy indicates that the prices are kept low as possible, prioritizing student access. A “high” tuition philosophy indicates that the state uses a “high tuition, high aid” model where tuition prices are set high but the state disburses high amounts financial aid, primarily to students with need. States with “high” tuition philosophy would expectedly have tuition prices greater than other states. We also consider the tuition-setting authority in each state using the following characterizations as variables: state statute, constitution, governor, higher education board and individual institutions. The tuition-setting authority characterizations indentify which governing body/policy is primarily responsible for setting the price of resident, undergraduate tuition in public 4-year universities. We included this characterization in our analysis because prior research indicates that some types of governing bodies and policies traditionally set tuition prices higher than others. Descriptive Statistics To begin our analysis we examined descriptive data regarding: annual tuition change at the national and regional level, and the distribution of tuition policies and tuition setting authorities across states (Appendix A). From this analysis we found that the national average change in tuition prices varied significantly between 1998 and 2008 (Figure 1). 5 Tuition-Setting Authority and Policy Type Another finding of this initial analysis is that formal tuition policies were used by states to set tuition in a slight majority (52%) of cases (Figure 2). Of the three formal policy setting structures, tuition policies were most often established by a higher education governing board (28 % of cases), followed by state statute (18%), and the state’s constitution (6%). Though many states did not use a formal tuition policy to set prices, a self-described formal or informal policy was used in 87 percent of cases (Figure 3). Of these cases, a majority (61.4%) used a policy of low or budgetary need to set tuition prices. This is in contrast to self-described high policies, which were used to set tuition only 2 percent of the time Interestingly, the self-described tuition policies and the type of tuition-setting authority vary across states with the lowest 10-year average percent increase, suggesting that policies have limited effects on pricing. Tuition Price by Region, Policy Authority, and Type To continue our analysis we examined how tuition prices varied across region, policy type and authority. These results, available in Appendices B through D, appear to roughly follow the trend line shown in Figure 1 with none of three independent variables displaying any obvious divergence from the average. Average Annual Change – Tuition and Appropriations The following chart (Figure 4) illustrates the average national change in tuition compared to the average national change in appropriations to public higher education. As institutions receive less state appropriations, it would be expected that tuition prices would increase to compensate. Consistent with this expectation, the chart indicates that this inverse relationship exists. However, in 2006 and 2007 it appears that tuition rose despite increased appropriations. Unfortunately without measurements from 2008 and 2009 we cannot assess what may have caused this result. 6 Changes in State Fiscal Climate and Net Tuition The following chart (Figure 5) shows a comparison of the average annual percentage change in tuition with the average annual percentage change in tax revenues for all states. Initially we believed that when tax revenues are high, the growth in tuition would be lower than in years when tax revenue growth is low or negative. This hypothesis is based on the reasoning that public university systems will receive more state assistance when tax revenues are high, resulting in reduced pressure on tuition prices. However, as Figure 5 illustrates, this relationship does not appear to exist in our data. One possible explanation for this finding is that the effect of lower tax revenues on tuition prices is heavily lagged. Meaning, only after long periods do budgetary pressures cause tuition prices to change. If this is the case, the declines in tax revenues during the 2001 recession could have some responsibility for 7 increased in tuition prices 2003 through 2006. To test this theory we incorporated a lagged revenue variable into our research models. Data Analysis Methods To analyze tuition increases, we use a linear probability, time-series model, in which the dependent variable is the percentage change in the price of tuition and fees in each state, relative to the previous year. The price of tuition is based on the total charge to undergraduate resident students, including all necessary fees but not reducing the amount for any state appropriations or financial aid. To conduct our analysis, we compare five models that vary with the types of variables and the type of regression, including am OLS, fixed effects regression and multilevel regression. The explanatory variables in our model represent the factors that influence tuition the most, according to policy-makers and authors of current literature. In general, however, our explanatory variables can be characterized into two types: formal, institutional factors that influence tuition prices and other market (or economic) factors that influence tuition pricing. To gauge the correlation between state government influences on the price of tuition, we will include three key variables: Type of tuition policy (categorical variable) Whether the policy is formalized in statute (dummy variable) Governing body that sets tuition price (categorical variable) To estimate the economic factors within the state that influence the price of tuition, we will include the following variables: Lagged % annual tuition change Enrollment for 4-Year public institutions Enrollment (and lagged enrollment) Private enrollment Proportion of private enrollment to undergraduate enrollment Population Bachelor degrees production Amount of state financial aid per student Percent tax revenue change (and lagged revenue change) Percent appropriation change (and lagged appropriations change) Regression Model - Development To conduct our analysis, we used five statistical models, including three OLS regression, a fixed-effects and multilevel model. The first model, an OLS regression, serves a control model for which we compare the findings of our additional models. In the second model, we include the lagged change in tuition, current enrollment, change in appropriations and change in state revenues, aiming to identify how these additional factors correlate with tuition. Notably, all these factors are statistically significant in the second model. The third model introduces the types of tuition policy and tuition setting-authority, all of which we found to be insignificant. We then include a fixed-effects model, aiming to isolate the unchanging characteristics of each state from the factors that we believe correlate with tuition change. With little variation in our policy data, we removed these variables from our final model, along with the variables for region. The lack of variation in 8 tuition polices across states limited the usefulness of a fixed-effects model, causing these variables to be insignificant or dropped. However, we believed there would be enough variation between region and policy type, and so we also analyzed a multi-level model. This fifth model assessed the random effect of having a formal tuition policy across regions on tuition prices. The results of these five models are presented below (Table 2). Table 2: Model Results Variable Name Model 1 Coef. P>t Model 2 Coef. P>t Model 3 Coef. P>t Model 4 Coef. P>t Model 5 Coef. P>t Policy Type: High - - - - 0.0408 0.440 (dropped) - 0.0131 0.807 Moderate - - - - 0.0064 0.824 (dropped) - -0.0120 0.650 Low - - - - -0.0201 0.407 (dropped) - -0.0322 0.191 Budget Need - - - - 0.0218 0.380 (dropped) - 0.0013 0.959 Other - - - - -0.0344 0.265 (dropped) - -0.0397 0.194 -0.0056 0.703 -0.0065 0.642 - - - - -0.0178 0.542 Board - - - - -0.0342 0.126 (dropped) - 0.0000 - Constitution - - - - -0.0498 0.129 (dropped) - 0.0000 - Statute - - - - 0.0197 0.353 (dropped) - 0.0000 - -0.0023 0.959 -0.0139 0.745 -0.0465 0.335 0.5968 0.158 -0.0044 0.921 Lagged % Tuition Change - - -0.2347*** 0.000 -0.2757*** 0.000 -0.4146*** 0.000 -0.2707*** 0.000 Enrollment/1000 - - -0.0033*** 0.000 -0.0032*** 0.000 -0.0026*** 0.009 -0.0032*** 0.000 Lagged Enrollment/1000 0.0002 0.301 0.0034*** 0.000 0.0033*** 0.000 0.0030*** 0.003 0.0033*** 0.000 Private Enrollment/1000 0.0003 0.153 0.0001 0.563 0.0003 0.102 0.0014 0.118 0.0003 0.113 Formal Policy Tuition Setting Body: Constant Proportion Private 0.0321 0.599 0.0288 0.619 0.1137** 0.087 0.0478 0.811 0.0806 0.113 -0.0253*** 0.002 -0.0161** 0.052 -0.0204** 0.017 -0.1980** 0.039 -0.0156* 0.051 Bachelor Degrees Produced/1000 0.0052* 0.068 0.0042 0.128 0.0047* 0.099 0.0209* 0.078 0.0025 0.321 Aid Per Enrollment/1000 0.0425 0.196 0.0364 0.244 -0.0125 0.741 -0.0237 0.800 0.0076 0.817 Population/1000000 % Revenue Change - - 0.0926** 0.041 0.0880* 0.052 0.0817* 0.072 0.1025** 0.021 0.0761* 0.083 0.1042** 0.017 0.1104** 0.012 0.1140** 0.013 0.1107*** 0.010 - - -0.2313** 0.013 -0.2361** 0.015 -0.1857* 0.061 -0.2060** 0.029 -0.1280 0.131 -0.1465* 0.077 -0.1410 0.101 -0.0560 0.533 -0.1203 0.151 SE -0.0003 0.991 0.0020 0.942 -0.0242 0.421 - - - - NE -0.0203 0.498 -0.0126 0.656 -0.0074 0.796 - - - - Plains -0.0186 0.580 -0.0150 0.638 0.0239 0.500 - - - - MW -0.0137 0.660 -0.0069 0.816 -0.0382 0.249 - - - - SW 0.0444 0.162 0.0606 0.045 0.0491 0.118 - - - - N= 299 N= 293 N= 293 N= 293 N= 293 R2 = 0.0366 R2 = 0.1086 R2 = 0.1574 R2 = n/a R2 = n/a Lagged % Revenue Change % Appropriation Change Lagged % Appropriation Change Region: Other Statistics *** = p < .01, ** = p < .05, * = p < .1 9 Regression Model - Findings Analyzing the results of the models, we come to following findings on how these factors correlate with tuition change: Tuition Policy and Tuition-Setting Authorities To examine the effects of policies on tuition pricing, we analyzed the general effects of all types of tuition policies and tuition-setting authorities. Using a dummy variable to indicate whether the state had any type of formal tuition policy, we found the effects of a formal tuition policy to be insignificant in the first two OLS models. This finding is reaffirmed by the results of our multi-level model (Appendix B). This model found only a small amount of variance (.03 percentage points) in tuition prices in states with formal policies. Separating the policies into four types (low, medium, high, budget constraints) in the third, OLS model, the correlation of policies onto tuition change was still insignificant. This finding is consistent with the previous researched, as discussed in the literature review earlier. However, we also recognize that the data on tuition policies had little variations within each state over the 10 years, without which the tuition policies would be insignificant in any of the models. Lagged Annual Change in Tuition Across all five models, the previous year’s percent change in tuition was significant, indicating its importance in affecting tuition change. Our research indicates that an increase in the previous year’s tuition leads to a percentage point decrease in the current year’s tuition. That is, tuition-setting authorities may be likely to increase (or even decrease) tuition if tuition increased during the previous year. Conversely, tuition-setting authorizes might be less inclined to raise to tuition after increasing tuition during the previous year due to political pressures or uncertainty in how the market for higher education will react. Regardless, this finding strongly suggests that the previous year’s tuition change largely affects the current year’s change in tuition. Bachelor Degree Production Our research also indicates that bachelor degree production and tuition change are positively correlated. In four of our models, we found bachelor degree production significant (p<0.10), albeit with a relatively low coefficients. A potential reason for this result is that bachelor degree production serves as a proxy for demand for higher education. Consistent with economic theory, when demand is higher prices will rise. Population Our analysis also found that population and tuition change were inversely correlated, indicating that an increase in state’s population leads to a decrease in the percentage point change in tuition. Previous research explains this correlation by noting that an increase population may lead to more tax revenues available to appropriate to higher education or that larger states have more infrastructure available to provide higher education at a lesser cost per student. We believe that both explanations may be true, along with the possibility that population correlates with other unobserved factors which are also correlated with tuition change. Tuition and Revenues Of these results the most surprising finding is that the relationship of tuition prices and tax revenues is opposite our initial hypothesis. When we designed our model we anticipated that these variables would have an inverse relationship; that is, when tax revenues fall, tuition increases (and vice versa). However, 10 our results show that the opposite is true, with a one percentage point increase in the previous year’s tax revenues resulting in an 11 percentage point increase in tuition prices (Table 1). We believe this result is caused by two factors. First, that the anticipated effect of revenues on tuition is being captured by the appropriation variables used in our model which do have an inverse relationship with tuition prices. Second, that increased tax revenues represent periods of economic growth during which policy makers are more likely to increase tuition prices than in recessionary periods. Tuition and Enrollment Another result of our analysis is that current enrollment and lagged enrollment have opposite effects on tuition prices. This result means that for every thousand students increase in enrollment, tuition will be 0.32 percentage points lower. By contrast, tuition will be 0.33 percentage points higher for every thousand students enrolled in the previous year.12 A possible interpretation of this finding is that an increase in enrollment creates more tuition revenues, lowering the need to increase prices to meet operating costs. Insignificant Correlations: Region, Aid per Full-Time Equivalent and Private Enrollment Following the findings of previous research, we consider region in our analysis, aiming to replicate their findings. Surprisingly, however, region was not significantly correlated with tuition change in any of our models, with only one exception.13 The results of our multi-level model reaffirm this finding, as the model estimated only a 0.03 percentage point variance in annual tuition prices across regions (Appendix B). The statistical insignificance of region led us to question why our models did not capture the correlation; however, we did not reach any reasonable explanations. Also in contrast to our expectations, we found that state need-based financial aid was not correlated with tuition change. As more states move towards a “high tuition-high aid” tuition policy, we expected that an increase in tuition would correlate with an increase in financial aid. However, our models suggest that tuitions increases do not correspond in an increase in financial aid per student. Lastly, when accounting for policy type and tuition setting authority, private enrollment and proportion of private enrollment becomes relevant. However, private enrollment is only slightly insignificant across all models, suggesting the market for private higher education slightly influences the pricing of public tuition. For instance, tuition-setting authorities may increase tuition if they believe that more students are willing to attend private universities and pay higher tuition prices. However, another “unobserved” economic factor might explain this correlation, such as general growth in state’s economy or increase in inflation. Both these economic factors might lead to an increase in private enrollment and a greater market tolerance for an increase in tuition. Discussion and Conclusions Returning to the focus of our original question of tuition policy, our analysis finds that tuition change is uncorrelated with state policies or tuition-setting authorities. Though policy and tuition-setting authority were insignificant, we identified several significant factors, including the change in the previous year’s tuition and appropriations, and the current year’s change in tax revenue and enrollment. 12 To test the strength of these opposing effects we included multiple lagged enrollment variables to see if the results would change. These variables were insignificant at the 10 percent level and had no impact on the original variables. 13 The dummy variable for the SW region was statistically significant in one model, and the p-values were lowest of all regions, (p = 0.162 and p = 0.118). 11 Possible Model Improvements While providing helpful characterizations, the results of the SHEEO survey demonstrate the complexity of tuition policies; many states have policies that are composed of elements that fall outside of SHEEO’s survey characterizations or the type of policy is more complex than a simple characterization while also varying slightly year to year. Moreover, state tuition policies change incrementally over time, and the SHEEO characterizations only provide rough depictions of the policies. A more thorough analysis would identify how key elements of tuition policies change each year within each state; unfortunately, we could not identify a reliable data source with this information for our analysis. We believe that identifying longitudinal changes in state tuition policies would allow for a more complete statistical analysis. As previously mentioned, the lack of variation in our tuition policies data prevented the use of fixed effects and multi-level models to analyze our key explanatory variables. Improved tuition policy data would provide the variation necessary to use these statistical methods and allow us to better discern how tuition prices are established. Potential for Future Analysis As Hearn notes, tuition costs tend to drift upward when budgets tighten, as institutions tend to raise tuition without fear of market retribution. Tuition seems to rise with the constraining of budgets along with other immediate political, social influences, and the economic context of the time. Identifying the cause of this discrepancy could be the focus on future research into the relationship between tax revenues and tuition prices. In our analysis, the tax revenues variable functions as a broad measure of both the economic and political climate in which tuition prices are set; however, tax revenues affect state budgeting but also reflect the strength of the state’s economy. Thus, the correlation of tax revenues and tuition change is complex, making it difficult to identify how policy relates to changes in tax revenues. Further analysis on how tax revenues correlate with tuition change, particularly during recessionary periods, will inform state policy-makers on the potential for increases during future years. Policy Implications Tuition policies continue to interest policy-makers, especially during recessionary periods. The current situation in Washington, for example, represents how policy-makers could use our findings to shape tuition policies. Specifically, Washington state institutions recently experienced one of the largest annual increases in undergraduate tuition. While legislation caps annual increases at 13% for the coming 3 years, this increase reflects a distinct change in policy that previously limited undergraduate tuition increases to 7% in state statute. As a result, the Washington legislature recently tasked the HECB with studying tuition policies and recommending a comprehensive policy for the state. (Currently, Washington has no formal comprehensive policies, but state statue limits the percent annual increase for each institution.) Recently, the HECB released a draft of their findings, recommending that the state to fund no less than 55 percent of undergraduate instructional costs at the six baccalaureate institutions. Further, it would limit the amount of instructional costs provided by tuition to 45 percent. Though our results show that tuition policies have no discernable effect on tuition prices we believe that this policy could stabilize tuition prices. A predictable tuition policy would link tuition pricing to tuition prices, appropriations and tax revenues, because, as our findings demonstrate, these factors are most likely to change in correlation with pricing. 12 Appendices: Appendix A: Descriptive Statistics Variable Percent Tuition Price Change N 550 Mean 0.025 Std. Dev. 0.100 Min -0.380 Max 0.929 Public Enrollment 550 189780.1 242908.5 15324.0 1731754.0 Private Enrollment 450 76885.9 97486.3 950.0 525859.0 Proportion of Total Enrollment Private 450 0.666 0.163 0.000 0.933 Bachelor Degrees Produced 500 17295.6 17248.8 1232.0 112661.0 Percent Revenue Change 500 0.075 0.129 -0.498 0.856 Population 550 5770874.0 Formalized Tuition Policy Self-Described Tuition Policy: High Budgetary Need Low Moderate No Philosophy Other Tuition Setting Authority: Board Constitution Informal Statute 550 0.520 0.500 0 1 529 529 529 529 529 529 0.021 0.270 0.312 0.166 0.125 0.104 0.143 0.445 0.464 0.373 0.331 0.306 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 551 551 551 551 0.279 0.060 0.479 0.180 0.449 0.238 0.500 0.384 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 6343437.0 479602.0 36800000.0 13 14 Appendix E: Data Dictionary Variable Name Year Year Variable Type Time State State Panel Population Estimated State Population per year SE Southeast States (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA) Northweast States (CT, DE, ME, MD, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT, WV) Plain States (CO, MT, ND, SD, UT, WY) Midwest States (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, NE, OH, WI) Southwest States (AZ, CA, HI, NV, NM, OK, TX) Northwest States (AK, ID, OR, WA) Tuition should be high. Dummy Tuition should be moderate. Tuition should be as low as possible Tuition policy is guided by institutionallevel philosophy or budgetary needs. Dummy NE Plains MW SW NW High Moderate Low Budget Need Description Continuous Dummy Hearn, James C., Griswold, Carolyn P., Marine, Ginger M. Region, Resource, and Reason: A Contextual Analysis of State Tuition and Student Aid Policies. Research in Higher Education, Journal of the Association for Institutional Research, Vol. 37, 3, 1996. Dummy Dummy Dummy Dummy Dummy Dummy Dummy None Not Formalized Dummy Statute State Statute Dummy Board Rule State higher education board rule or policy State Constitution Dummy Dummy Variable indicating whether the tuition philosophy is formalized in state constitution, by legislative statute, by state rule, board rule or Dummy Formalized U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). "State Tax Revenues". Retrieved 25 October 2009 from U.S. Census http://factfinder.census.gov. In response to: "Which of the following statements best describes the overall tuition philosophy or approach for public colleges and universities in your state?" State Higher Education Executive Officers. State Tuition, Fees and Financial Assistance Policies for Public Colleges and Universities, 2005-06. November 2006.www.sheeo.org Dummy Other Constitution Source Dummy In response to: "Is this tuition philosophy formalized in the state constitution, by legislative statute, by state rule, board rule or policy, or not formalized?" State Higher Education Executive Officers. State Tuition, Fees and Financial Assistance Policies for Public Colleges and Universities, 2005-06. November 2006.www.sheeo.org 15 policy. Percent Net Tuition Increase Annual Percentage Change in Net Tuition Continuous Proportion National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics, US Department of Education, Institute of Education Science, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/ Total Annual Revenue Total State Tax Revenues Continuous U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). "State Tax Revenues". Retrieved 25 October 2009 from U.S. Census http://factfinder.census.gov. Percent Change Revenues Annual Percentage Change in State Tax Revenues Continuous Proportion U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). "State Tax Revenues". Retrieved 25 October 2009 from U.S. Census http://factfinder.census.gov. Aid/enrollment Allocated state needbased aid per student The amount allocated by the state per fulltime equivalent Continuous National Center for Education Statistics Continuous The number of bachelor degree graduates per state per year The total annual undergraduate enrollment of all private, accredited 4year insitutions within the state. The proportion of the state's total enrollment that are enrolled in private institutions The total amount of resource allocated for financial aid divided by the current enrollment Total state population Continuous Delta Cost Project. Trends in College Spending. 2009, Delta Project on Postsecondary Education Costs, Productivity and Accountability. www.deltacostproject.org National Center for Education Statistics Continuous National Center for Education Statistics Continuous Proportion National Center for Education Statistics Continuous National Center for Education Statistics Continuous US Census The percent change in the amount appropriated by the state per FTE Continuous Proportion National Center for Education Statistics Appropriations per FTE Bachelor Degree Production Private Enrollment Proportion of Private Enrollment Aid per enrollment Population Percent Appropriations Change 16 References Delta Cost Project. Trends in College Spending. 2009, Delta Project on Postsecondary Education Costs, Productivity and Accountability. www.deltacostproject.org Hearn, James C., Griswold, Carolyn P., Marine, Ginger M. Region, Resource, and Reason: A Contextual Analysis of State Tuition and Student Aid Policies. Research in Higher Education, Journal of the Association for Institutional Research, Vol. 37, 3, 1996. Shin, Jung-cheol, Sande Milton, "Rethinking Tuition Effects on Enrollment in Public Four-Year Colleges and Universities," The Review of Higher Education, 2006, 29, 2, pp.213-237. State Higher Education Executive Officers. State Tuition, Fees and Financial Assistance Policies for Public Colleges and Universities, 2005-06. November 2006.www.sheeo.org State Higher Education Executive Officers. State Higher Education Finance, FY 2008 (2009). www.sheeo.org Data National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics, US Department of Education, Institute of Education Science, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/ National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs. Annual Survey Report, 1989-90 through 2004-05. http://www.nassgap.org/ U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). "State Tax Revenues". Retrieved 25 October 2009 from U.S. Census http://factfinder.census.gov.