Use of Simulation in..

advertisement

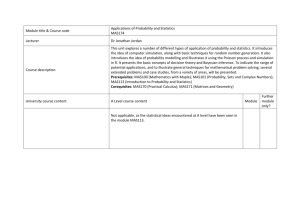

4.3.10 USE OF SIMULATION IN THE CURRICULUM 03/09, 08/09, 01/10, 05/10, 02/12, 05/13 PURPOSE Simulation is a valuable teaching strategy in education. Simulation allows for learning or reinforcing specific concepts or technical skills, organizational skills, and assessment skills. It cannot, however, replace the patient – health care provider relationships and accountability that comes with caring for real patients. Therefore, simulation is best used as an adjunct to clinical practice, but should not replace clinical hours in totality. Simulation is used to support theory as a teaching method to be utilized at faculty discretion. DEFINITION Simulations are activities that mimic the reality of a clinical environment and are designed to demonstrate procedures, decision-making and critical thinking through techniques such as roleplaying and the use of devices such as interactive videos or manikins (NCSBN, 2005, p. 2). The level of simulation fidelity is defined by the extent to which simulation mimics reality (Jeffries, 2007; NLN, 2011). Fidelity is determined by the environment, the tools and resources used, and many factors associated with the participants (INACSL, 2011). High fidelity provides a “close to life” situation allowing for a high level of interactivity between the nurse and patient, with exhibition of appropriate signs and symptoms. High fidelity may incorporate a sophisticated, full scale, computerized patient simulators, virtual reality or standardized patients that are extremely realistic (e.g., the manikin’s chest rises and falls). Moderate fidelity incorporates sophisticated technology in which the participant relies on a two-dimensional focused experience to problem solve, make decisions, and/or perform a skill. Manikins may be utilized to make the simulation more realistic (e.g. a manikin’s with the ability to auscultate heart sounds and breath sounds but the chest does not rise and fall). Low fidelity incorporates static tools (e.g., case studies, role-playing, injection models, IV arms, or static manikins with no extra features such as breath and heart sounds, voice, or any interactive features) to immerse students in a clinical situation or to practice a specific skill. PROCEDURE I. Simulation in Theory a. Simulation time counts in a 1 to 1 ratio in relation to theory time (i.e. 1 hour of simulation equates to1 hour of theory.) b. Simulation time in theory may be identified within the syllabus (i.e. placement within the assignments/activities, under the unit it falls, or within the required assessments in the syllabus). Document1 pg 1 II. Simulation for Clinical (High fidelity simulation only) a. Simulation time when used for clinical hour replacement, shall be counted in a 1 to 3 ratio (e.g. 2 simulation hours equates to 6 clinical hours). Rationale: The simulation experience is an intense, concentrated experience without the inherent downtime that occurs in clinical. b. For every 1 credit of clinical, a maximum of 2 hours of simulation may be used in place of clinical hours. (See examples below) Examples: Clinical Credits 1.0 credit 1.5 credits 2.0 credits Max. Simulation hours allowed 2 hours 3 hours 4 hours Max. Clinical Hours Replaced 6 clinical hours 9 clinical hours 12 clinical hours c. High fidelity simulation will replace no more than 15% of the student’s total clinical time in the college program. d. Exceptions to the schedule outlined in item II. b. above may occur in consultation with and approval of the appropriate Program Director and/or Dean of Academic Affairs. III. Simulations using resource lab space or resources must be coordinated with the Health Sciences Resource Center (HSRC) Coordinator ahead of the planned simulation, see policy: Planning for Specific Course and Simulations in the Health Sciences Resource Center (HSRC). Simulations are designed to support clinical practice. As such, students are expected to comply with the same expectations and policies in simulation as they would in clinical, including dress code, preparation, and professional behavior. IV. Course facilitators must implement use of the Health Sciences Resource Center (HSRC) Consent for Recording Documentation of Participation in Clinical Simulation at the beginning of a course that involves simulation. This form is only required if faculty intend to retain the recording beyond the debriefing period. Faculty will retain the simulation and consent for a period of two years. A student at any point may withdraw consent. V. References Cannon-Diehl, M. R. (2009). Simulation in health care and nursing: State of the science. Critical Care Nurse Quarterly, 32(2), 128-136. Hodge, M., Martin, C. T., Tavernier, D., Perea-Ryan, M., & Alcala-Van Houten, L. (2008). Integrating simulation across the curriculum. Nurse Educator, 33(5), 210-214. International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (2011). Standard I: Terminology. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 7(4S), S3-S7. Jarzemsky, P. A., & McGrath, J. (2008). Look before you leap: Lessons learned when introducing clinical simulation. Nurse Educator, 33(2), 90-95. Document1 pg 2 Jeffries, P.R. (2007). Simulation in nursing education; From conceptualization to evaluation. New York, National League of Nursing. Jeffries, P. R. (2005). A framework for designing, implementing, and evaluating simulations used as teaching strategies for nursing. Nursing Education Perspectives, 26(2), 96-103. Li, S. (2007). The role of simulation in nursing education: A regulatory perspective [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from National Council of State Boards of Nursing: www.ncsbn.org. National Council of State Boards of Nursing (2009). The effect of high-fidelity simulation on nursing students’ knowledge and performance: A pilot study (Research brief vol. 40). Chicago: Author. National Council of State Boards of Nursing Practice, Regulation, and Education Committee (2005, August). Clinical instruction in prelicensure nursing programs [White paper]. Retrieved from NCSBN: www.ncsbn.org National Council of State Boards of Nursing Practice, Regulation, and Education Committee (2006, July). Evidence-based nursing education for regulation [White paper]. Retrieved from NCSBN: www.ncsbn.org National League of Nursing, Simulation Innovation Resource Center (2011). SIRC Glossary. Retrieved from NLN: http://sirc.nln.org Nehring, W. M. (2008). U. S. Boards of nursing and the use of high-fidelity patient simulators in nursing education. Journal of Professional Nursing, 24(2), 109-117. Nehring, W. M., & Lashley, F. R. (2004). Current use and opinions regarding human patient simulators in nursing education: An international survey. Nursing Education Perspectives, 25(5), 244-248. Parker, B. C., & Myrick, F. (2009). A critical examination of high-fidelity human patient simulation within the context of nursing pedagogy. Nurse Education Today, 29, 322-329. Rothgeb, M. K. (2008). Creating a nursing simulation laboratory: A literature review. Journal of Nursing Education, 47(11), 489-494. Simpson, R. L. (2003). Welcome to the virtual classroom. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 27(1), 8386. Document1 pg 3