DOWNLOAD in Word (docx 34kB) - Northern Territory Government

advertisement

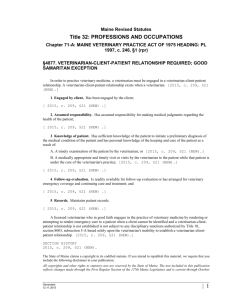

COMPLAINTS INVESTIGATED AND DETERMINED BY VETERINARY BOARD OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY It is Board policy to encourage patrons who have a problem with their veterinarian to talk it over with the veterinarian in the first instance. Often problems stem from misunderstandings that may be resolved by seeking clarification or talking it through. However, the Board has a statutory obligation to investigate written complaints regarding a veterinarian’s professional or ethical conduct. Section 28 of the Veterinarians Act provides that: “28. Meaning of misconduct (1) For the purposes of this Act, a registered veterinarian or a person formerly registered under this Act is guilty of misconduct if he or she – (a) is guilty of improper or unethical conduct, or is incompetent or negligent, in or in connection with the provision of a veterinary service; (b) contravenes or fails to comply with this Act, a prescribed code of conduct or a condition to which his or her registration is subject; or (c) uses in connection with the provision of veterinary services a qualification or title relating to his or her competence to provide such services that is not shown in his or her entry in the Register. (2) For the purposes of subsection (1)(a), a registered veterinarian or a person formerly registered under this Act is taken to be incompetent if he or she is unable or fails to uphold or maintain contemporary professional standards. SUMMARY OF OUTCOMES OF COMPLAINTS INVESTIGATED AND DETERMINED BY THE VETERINARY BOARD OF THE NT IN 2012 In case 1, the complainant made allegations of potential breaches of the prescribed Code of Conduct in relation to: the standard of the suturing following a cat spay (which needed to be re-sutured by another veterinarian after hours as the cat chewed out some of the stitches); a lack of information on post-operative care; and failure to provide an estimate of costs. The Board’s investigation found that: (1) a ground of misconduct could not be substantiated against the veterinarian who performed the initial procedure on the basis that the evidence demonstrated that: A quote was given when the surgery was booked (in line with the practice protocol for estimating costs for spays) and the client paid the account prior to the surgery. The veterinarian had performed a standard midline ovario-hysterectomy and that the anaesthesia and surgery were uneventful. The incision was closed in three layers, in line with current veterinary standards. (This was indicated in the veterinarian’s clinical notes and confirmed by the statements from the veterinary nurses and the clinical notes made by the second veterinarian at the time of the second procedure. The latter notes stated that, at the time of the after-hours re-admission, some internal sutures were still intact, but most were chewed.) In meeting her responsibility under the Code of Conduct to ensure to the best of her ability that staff under her supervision carry out their duties effectively, it was reasonable for the attending veterinarian to expect (without specific direction) that the client would be provided with information on appropriate post-operative care when the pet was discharged, given the veterinary nurses’ familiarity with and understanding of the clinic’s established protocol on the appropriate post-operative care information to be given to pet owners. The practice records did not confirm that the paperwork given to the complainant’s wife by the veterinary nurse/practice manager when she collected the cat after the initial procedure actually included the standard “Surgery Discharge Information Sheet”. However, his stated recollection of the verbal advice that he provided regarding appropriate post-operative care and the need to stop the cat from chewing at the suture line, was plausible. (2) By his own admission, the second veterinarian did not give the client an estimate of the cost of the after-hours procedure. He stated that he often leaves the discussions on costs to the practice manager, but acknowledged that it is ultimately his responsibility to ensure that the likely cost of treatment is communicated to the client. The Board completed its investigation by determining that: (1) (2) the complaint against the veterinarian who performed the initial procedure should be dismissed and no further action taken; and the second veterinarian should be issued with a reprimand for failing to ensure that the pet owner was made aware of the likely cost of treatment, and no further action taken. The Board noted that since receiving this complaint, revisionary staff training had taken place on the importance of applying and adhering to the established practice protocols and complying with the Code of Conduct and agreed that the complainant could be advised of this positive outcome. Page 2 Case 2 was a complaint against two veterinarians at a regional veterinary hospital regarding the treatment given to the complainants’ dog following a snake bite at a remote community some 450 kilometres from the clinic. The complaint listed allegations of “failure to take instructions or obtain informed consent”; “failure to give appropriate treatment” and “unprofessional conduct” and subsequently added the allegation that “the practice was also at fault in respect of its failure to have in place appropriate protocols and procedures”. The dog was presented for treatment approximately 8 hours after envenomation. Based on “having come all this way”, the dog owners determined to seek to have the dog treated rather than euthanased. They were annoyed about having to sign consent forms in advance of each treatment option, and in particular, the associated agreement to pay for the costly anti-venom. Unfortunately, after incurring a substantial bill, the dog died and the owners refused to pay. After a thorough investigation, the Board found that grounds for misconduct were not substantiated and determined that the complaint against each of the veterinarians be dismissed and no further action taken. Reasons for Decision The Board was satisfied that, contrary to the complainants’ allegations, the practice records demonstrated that: (1) The complainants: did not request euthanasia (as claimed in their complaint); were given the option for euthanasia on several occasions, but decided to treat; were provided with sufficient information on: - the poor prognosis and potential complications; - the basis of the initial and on-going treatment regime; - the likely extent of the costs being incurred; to enable them to provide their “informed” consent for the courses of action taken and treatment given. (2) Both veterinarians acted appropriately and administered correct veterinary care and treatment based on their professional assessment and clinical observations. (3) All staff took cognizance of the complainants’ vulnerable, emotional state and kept the complainants apprised of their dog’s condition; and (4) The practice policies and protocols on the need to obtain informed consent and to initially recommend brown snake anti-venom when the snake has not been positively identified, are satisfactory and comply with governing legislation and current standards of veterinary practice.