Supplementary materials and methods. Patients in the BD and

advertisement

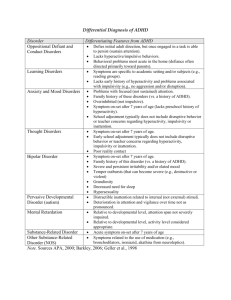

Supplementary materials and methods. Patients in the BD and ADHD groups were selected using the following inclusion criteria: 1) age between 18 and 55 years; 2) diagnosed with Type-II BD or adult ADHD, respectively, according to the DSM-IV, using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First 1996); and 3) euthymia scores less than or equal to 8 points, according to the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), (Montgomery and Asberg 1979) and less than or equal to 6 according to the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young, Biggs et al. 1978) for at least 8 weeks and with no change in medication type or dosage over 4 months. No patient received antipsychotics. Controls (CT) were group-matched to the clinical groups for sex, age, handedness, and years of education. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) other Axis-I diagnoses, except for generalized anxiety disorder, and 2) a history of intellectual disability, neurological disease, or any clinical condition that might affect cognitive performance. All patients with ADHD were taking methylphenidate, which was suspended on the day of EEG recordings because this medication affects cognitive performance (Volkow, Wang et al. 2004). CT subjects were selected from a pool of volunteers who did not have a history of drug abuse or a family history of neurodegenerative or psychiatric disorders. EEGs were recorded in a separate session on the same day. During the experiment, participants and EEG recordings were monitored to assure that subjects maintained vigilance and did not fall asleep. Ethics All participants provided written informed consent in agreement with the Helsinki declaration. Although some of the participants have diagnosis of ADHD or bipolar conditions, any of those disorders implied a reduced capacity to consent. The Ethics Committee of the Institute of Cognitive Neurology (INECO) approved this study. Clinical, symptomatic and neuropsychological assessment All participants completed a series of psychiatric and behavioral questionnaires to establish a clinical symptom profile that included depression, mania, impulsivity, anxiety, attention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scores (see Table 1). Depression was rated using the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; (Beck, Steer et al. 1996) and the MADRS. Mania and impulsivity were rated using the YMRS and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) (Barratt 1985), respectively. The symptomatic profiles of ADHD subjects were obtained from inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scores on the ADHD Rating Scale for Adults (Murphy and Barkley 1996). A neuropsychology test evaluated participants’ memory and frontal function. Memory was evaluated using the Rey Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) (Rey 1958 ), which examines verbal learning, immediate and delayed recall. Frontal function was evaluated with the INECO Frontal Screening (IFS) (Torralva, Gleichgerrcht et al. 2011), which provides a global score of executive function as indexed by the following subtasks: motor programming, conflicting instructions, gono go, backward digits span, spatial working memory, abstraction capacity and verbal inhibitory control. The Trail Making Test- B was used to assess attentional flexibility and attentional speed. The Backward Digit Span, Letter-Number Sequencing and Arithmetic tests were used to assess mental manipulation and working memory. Inhibitory control was assessed using a go-no go task that included correct, incorrect and omitted response percentages and reaction times. A phonological fluency task was also included. Supplementary results Clinical evaluation and Neuropsychological assessment As expected, the groups differed significantly on the ADHD-RS-Inattention subscale (F(2,31)=8.70, p=0.0012) and the ADHD-RS-Hyperactivity/impulsivity subscale (F(2, 31)=4.7, p=0.01). Post-hoc comparisons (MS=33.32; df =27.00) showed that ADHD participants had significantly higher scores for inattention (p=0.001) and for hyperactivity/impulsivity (p=0.01) as compared with the CT group. Differences between groups were observed for BIS-11 scores (F(2, 31)=5.9, p=0.007). Post-hoc comparisons (MS=375.86; df =27.00) showed that BD subjects (p=0.005) had significantly higher scores than did CT subjects. We observed no differences between groups for BDI-II scores (F(2, 31)=3.02, p=0.065), MADRS scores (F(2,27)=0.57, p=0.56) or YMRS scores (F(2, 31)=2.15, p=0.13). On memory tests, significant differences between groups (F(2,31)=5.76, p=0.007) were observed in the recognition phase. Post-hoc comparisons (MS=1.74; df =31.00) revealed worse performance in the ADHD group (p=0.005) as compared with the CT group. Regarding executive function measures, no differences between groups were observed on the total IFS score. On the go-no go task, go trial accuracy (F(2,31)=3.57, p=0.04) and omission response percentage (F(2, 31)=3.57, p=0.04) differed significantly between groups. Post-hoc comparisons (MS=170.05; df =27.00) revealed lower accuracy (p=0.03) and more omission errors (p=0.003) in BD subjects as compared with control subjects (CT; p=0.03). Scores on the verbal Phonologic Fluency Task were lower for the BD (p=0.02) and ADHD groups (p=0.02) as compared with the CT group. Scores on the verbal Phonologic Fluency Task differed significantly between groups (F(2, 27)=6.36, p=0.005). Post-hoc comparisons (MS=24.9; df =27.00) showed lower performance in the BD (p=0.02) and ADHD subjects (p=0.02) as compared with CT subjects. Summarizing, ADHD participants had significantly worse scores for inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity symptoms as compared with CT subjects. The groups did not differ significantly on BDI-II, MADRS or YMRS scores. No differences between groups were observed on executive function or attention tasks using a frontal screening assessment. Regarding other executive function measures, on the go-no go task, BD participants showed lower accuracy on go trials and more omission errors as compared with CT subjects. On memory tests (recognition phase), ADHD participants performed worse than did CT subjects. ADHD and BD participants presented lower scores than did CT subjects on the verbal phonologic fluency task (see Table 1). Supplementary References Barratt, E. S. (1985). Impulsiveness subtraits: Arousal and information processing. North Holland, Elsevier Science. Beck, A. T., R. A. Steer, et al. (1996). "Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients." J Pers Assess 67(3): 588-597. First, S., Williams and Gibbon (1996). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). Washington, DC American Psychiatric Association. Montgomery, S. A. and M. Asberg (1979). "A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change." Br J Psychiatry 134: 382-389. Murphy, K. and R. A. Barkley (1996). "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: comorbidities and adaptive impairments." Compr Psychiatry 37(6): 393-401. Rey, A. (1958 ). L'Examen Clinique en Psychologie. Paris, Press Universitaire de France. Torralva, T., E. Gleichgerrcht, et al. (2011). "Neuropsychological functioning in adult bipolar disorder and ADHD patients: a comparative study." Psychiatry Res 186(2-3): 261-266. Volkow, N. D., G. J. Wang, et al. (2004). "Evidence that methylphenidate enhances the saliency of a mathematical task by increasing dopamine in the human brain." Am J Psychiatry 161(7): 1173-1180. Young, R. C., J. T. Biggs, et al. (1978). "A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity." Br J Psychiatry 133: 429-435.