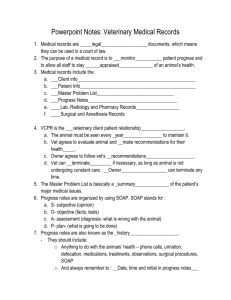

the e-assessment Guide (MS Word 1.4MB)

advertisement