An Observation of Beauty Practices Throughout

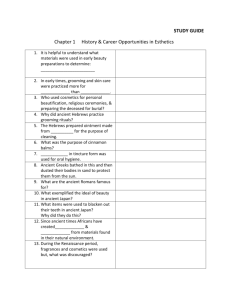

advertisement

An Observation of Beauty Practices Throughout History Posted by: Laura Hermoza (March 13, 2013) Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The cross-cultural desire for improving one's natural appearance is nothing new. The idea about what is aesthetically pleasing is a subjective one that aligns itself with what has been culturally acceptable throughout history. Dating back to the earliest civilizations, human beings have always taken on the task of improving themselves through sometimes harmful and even self-mutilating practices. The goal for changing oneself in a way deemed more beautifying may be an age-old concept, but the practices for doing so, even by unnatural methods, continue to this day—even if not in such extreme cases as once were. Though much of western civilization may view some ancient practices as inhumane and utterly bizarre by today’s standards, one practice that has never grown old is the art of wearing makeup. Dating back to the days of early Egyptians, the art of applying makeup has endured even through modern times. Ancient Egyptian men and women alike wore eye shadow daily. These eye shadow compounds were created using udju, a green paint made from copper ore and mesdemet, a combination that included dark lead. In addition to improving appearances, these early cosmetics also assisted in the prevention of infections and repelling insects. From viewing the multitudes of available cosmetics in today’s stores, it is interesting to note that not all forms of makeup were so benign, and some even posed health hazards. Throughout history, women have created and used powders made from such mainstays as arsenic, mercury and lead ore as a means of achieving a desirable pallid effect. In the early geisha tradition, Japanese women were known to whiten their faces with a paste concocted of bird droppings and rice. European women during the Middle Ages also strived to achieve a pasty white complexion through harmful mixtures. Sometimes, the inhaling of poisonous fumes or even the application of leeches achieved desired results. During the Elizabethan Age, many women aspired to imitate the looks of their noble queen, particularly her vibrant red hair. Often times, wigs were made using a combination of safflower petals and sulfur which sometimes caused women to grow ill and suffer extreme cases of nausea, headache, nosebleed and other ailments. Another source for altering hair came in the form of dyes. Iranian women, in ancient days, created dyes for hair which consisted of cow blood, henna and even tadpoles. Engrossing Gross Practices Some of the cosmetic concoctions used through the ages included berries for darkening the lips, the ends of charred matches to darken eyebrows and even urine for fading freckles and other blemishes. Taking a turn for the more grotesque, urine has played a key role in several betterment practices including dental hygiene. Because of its surprisingly effective properties in killing germs and preventing gum disease, urine was a popular base for gargling in Roman times and also proved successful in whitening teeth. This is because urine contains urea, ammonia and other germ-fighting agents. Urine is not the only bodily excrement that has been used throughout time. Reports show that ancient Greeks believed that the practice of bathing in crocodile dung gave one restorative and improving results. Believing the compound improved outer complexions, many ancients also took on the practice of drinking ox blood. Getting Physical Improving one’s physique sometimes required going beyond skin-deep to include deforming, reforming and self-mutilation. Even in ancient times, using one’s head was an important matter, but in many ancient cultures, the restructuring and reshaping of the head was equally important. Known cultures to have participated in such practices include Native American tribes, ancient Egyptians, Huns, Australian Aborigines, the Maya and many Germanic tribes. These cultures may have all shared in the practice of redesigning heads, but the shapes and skull designs varied greatly from culture to culture. Though designs varied, the method behind these practices all share in a similar modification process. While still in an infantile state of development (about one month old), babies were subjected to skull binding. The motive for such constructions is still unclear, but many historians believe elongated skull shapes depicted greater intelligence amongst ancient peoples. Head binding is not the only binding practice in history. Foot-binding is one of the most widely recognized and painful practices people are familiar with. The practice for binding the feet of women is believed to have begun in China around the 10th century. Originally intended for wealthy families, the practice soon expanded to include women of all distinctions and continued on well into the 1900s. Having tiny feet was seen as desirable in Chinese culture. Therefore, by the time a girl was still fairly young (between the ages of 6 and 14) she would undergo the painful procedure where nearly every bone in her foot was broken and then bound tightly around into a “lotus-shape.” A bound foot that was around three or four inches was ideal. Keeping with the tight constraints of beauty, many women throughout history have taken on the art of waist-line constriction. The most common method for doing so comes in the form of the corset. In order to achieve a desired hour-glass figure, a woman would tightly lace her waist in order to dramatically reduce her size. Though the corset first appears in history circa the 1500s, this fashion item saw its peak in popularity in the 19th and early 20th century. Sometimes made from whale bones, a corset was designed to reduce a waist size by up to 10 inches. Tight restrictions often resulted in internal physical issues including breathing problems, cracked ribs and even altered and displaced organs. Some women even resorted to having their lower ribs surgically removed in order to more comfortably tighten a restraining corset. The stretch for ideal beauty has included many elongated practices both historically and culturally. Some are still practiced this day. Body piercing is not considered odd by today’s standards, but the stretching of pierced cartilage-dominated body parts may be a little less familiar to western civilization. Throughout parts of Africa, and even areas surrounding the Amazon River in South America, many people practice the art of piercing such areas of the body, including ears and lips, with discs and stretching them until the intended lengthened size is achieved. Another neck-craning practice is the use of neck rings. Throughout African and Asian culture, women have been known to slenderize their necks through applying many layers of brass ring coils around the neck. These rings apply pressure to the collar bones causing it and the upper ribs to be pushed down. As a result, the neck will appear longer. Ideas for achieving beauty have undergone many developments throughout the ages, but one fact remains in the underlying tell-tale sign of human nature. Humans have always attempted to alter natural states of being in order to achieve some form of aesthetic betterment. Though the commonly accepted beauty practices in today’s world do not appear as odd as the aforementioned depictions, how will today’s seemingly “normal” beauty practices be viewed by tomorrow’s civilizations? Sources: beautifulwithbrains.com Beauty History: Cosmetics in Ancient Egypt. 2010 Crezo, Adrienne. “7 Historic (and Seriously Unhealthy) Beauty Practices.” MentalFloss.com. 2008. Wheatley, Michael J., MD. “History of Makeup.” WebMD Medical Reference. 2009. Winsor, Brooke. “Most Painful Cultural Beauty Practices.” Roadtickle.com