CIB 2005 Full Paper Model

advertisement

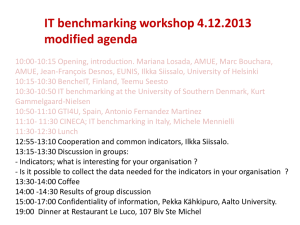

Benchmarking – A tool for judgment or improvement? Grane Mikael Gregaard Rasmussen, DTU Management, Technical University of Denmark gmgr@man.dtu.dk Abstract Change in construction is high on the agenda for the Danish government and a comprehensive effort is done in improving quality and efficiency. This has led to an initiated governmental effort in bringing benchmarking into the Danish construction sector. This paper is an appraisal of benchmarking as it is presently carried out in the Danish construction sector. Many different perceptions of benchmarking and the nature of the construction sector, lead to an uncertainty in how to perceive and use benchmarking, hence, generating an uncertainty in understanding the effects of benchmarking. This paper addresses these issues, and describes how effects are closely connected to the perception of benchmarking, the intended users of the system and the application of the benchmarking results. The fundamental basis of this paper is taken from the development of benchmarking in the Danish construction sector. Two distinct perceptions of benchmarking will be presented; public benchmarking and best practice benchmarking. These two types of benchmarking are used to characterize and discuss the Danish benchmarking system and to enhance which effects, possibilities and challenges that follow in the wake of using this kind of benchmarking. In conclusion it is argued that clients and the Danish government are the intended users of the benchmarking system. The benchmarking results are primarily used by the government for monitoring and regulation of the construction sector and by clients for contractor selection. The dominating use of the benchmarking results is judgment oriented and this is argued to generate competition among the contractors, thus, undermining the distribution of best practice and voluntary knowledge sharing among contractors. It is argued that benchmarking in the Danish construction sector to a certain extend constructs an overall comprehension of what constitutes project success. Keywords: benchmarking, construction, evaluation theory, effects 1. Introduction Benchmarking is a powerful concept and is widely considered to be essential to serious organizational improvement process (Chen, 2005; Dawkins et al, 2007). But through a quick glance at the literature on ‘benchmarking’ per se and ‘benchmarking in construction’ it becomes clear that ‘benchmarking’ is perceived and operates in many different ways in various countries and contexts (e.g. Cox et al., 1997; Beatham et al., 2004; Haugbølle and Hansen, 2006; Triantafillou, 2007; El-Mashaleh et al., 2007). The literature on benchmarking is also theoretically underexposed focusing on pragmatism and practice rather than epistemology (e.g. Cox et al., 1997; Bowerman et al. 2002; Moriarty and Smallmann, 2009). The literature on benchmarking in construction shows the same tendencies: The predominant part of the literature is pragmatic focusing on e.g. development of new benchmarking models and presentation of benchmarking cases and application of benchmarking results. Fernie et al. (2006) point out that ‘[...] it is also necessary to recognize that different industry sectors and organizations are characterized by recipes, logics and organizational routines that reflect a historical understanding of both context and practices. [...] [T]he philosophical study of causation, has been given very little attention in the construction literature and much more emphasis has been put on describing the ‘symptoms’ than unraveling their origins’ The different perceptions of benchmarking and the lacking attention on the underlying nature of construction, lead to an uncertainty in how to perceive and use benchmarking in the construction sector. This paper is an attempt to address this issue doing an appraisal of the present use of benchmarking in the Danish construction sector. Utilization focused evaluation theory and public benchmarking are brought into the discussion in order to transcend the existing benchmarking literature within construction research. The basis of this paper is taken from the governmental effort in bringing benchmarking into the Danish construction sector. These efforts include benchmarking of contractors, architects and consulting engineers that are involved in state construction projects and social housing projects. This paper will primarily focus on how benchmarking benefits the contractors, the clients and the Danish government, relative to whose interest that is taken into consideration. It will be emphasized that the development of benchmarking has increasingly undermined the intentions of distributing best practice and voluntary knowledge sharing among the contractors; substituting these with compulsive performance comparison that creates competition when clients uses the benchmarking results for contractor selection. This utilization of the benchmarking system will be discussed and be held together with the issue raised in the abovementioned quotation by Fernie et al. (2006). It is neither the aim of the paper to be prescriptive nor to favor one use of benchmarking rather than another. The paper should be regarded as a reflective contribution to the debate about the different effects of benchmarking, and as an attempt to widen the theoretical perception of benchmarking in the construction sector. 2. Two different types of benchmarking Two very distinct perceptions of benchmarking are used to address the issues and considerations associated with the effects, benefits and risks for benchmarking as it is carried out in the Danish construction sector. The two types are; public benchmarking comparable with benchmarking dominating the public sectors and best practice benchmarking as the perception of best practice benchmarking commonly used in the private sectors. 2.1 Best practice benchmarking This perception of benchmarking derives from the private industry and is built on trust, collaboration and a mutual benefit over a period of time. It is synonymously with the most prevailing interpretation of best practice benchmarking used in the private industry. It aims at gaining competitive advantage by means of continuous improvement of processes learned from the successful practices of others (Watson, 1993; Camp, 1995). Best practice benchmarking is not simply competitor analysis, espionage or theft from rival companies. It aims not simply to measuring the organization against the best in class and adopting their methods but on understandings of how to achieve superior performance by improving methods, practices and processes learnt from others (Watson, 1993; Zairi, 1997; Beatham, 2004; Moriarty and Smallman, 2009). The critical characteristic is the examination of processes. Benchmarking results are inapplicable, if there is provided no comprehension of the processes leading to the results. ‘Benchmarking is used to improve performance by understanding the methods and practices required to achieve world-class performance levels. Benchmarking’s primary objective is to understand those practices that will provide a competitive advantage; target setting is secondary’ (Camp, 1995, p. 15). Best practice benchmarking only uses results (indicators) from the benchmarking system to identify performance gaps and locate superior performance. Subsequently methods, practices and processes fit to the specific need of the organization are adapted from excelling companies (Camp, 1989). The evaluation theory has interesting similarities to benchmarking theory, e.g. Peter Dahler-Larsen (2008) addresses the consequences indicators give rise to when used in evaluation objectives. He points out that the learning element in the utilization of indicators is crucial in order to generate best practices, learning and continuous improvement. Indicators and the criteria set up for them must be under constant development, interpretation and adaption. The results must make sense and must be useful to those responsible for the processes that need improvement. He also (as Camp, 1995) points out that in the leaning objectives it is not sufficient to identify the performance gap. It is necessary to affiliate organizational processes to the results of the indicators in order to provide continuous learning and improvement. Ownership, involvement, reflection and relevance are keywords in using indicators with learning objectives (Dahler-Larsen, 2008). Another interesting perspective from the evaluation theory that addresses the utilization of indicators comes from Michael Quinn Patton (1997). He operates with program evaluation when using the concept utilization-focused evaluation. In comparison to best practice benchmarking, he introduces improvement-orientated evaluation; ‘Improvement-orientated evaluation [...] includes using information systems to monitor programs efforts and outcomes regularly over time to provide feed-back for fine-tuning a well established program. That’s how data are meant to be used in as part of a Total Quality Management (TQM) approach’ (Patton, 1997, p. 69). Similar to best practice benchmarking, this improvement-oriented evaluation focuses on improvement rather than rendering summative judgment of the evaluation results. It is orientated towards a gathering of data on strengths and weaknesses that are used to produce continuous reflections and innovation on where efficiencies can be made. Purpose, method and criteria for judging success must be decided by the intended users of the evaluation. The questions that the evaluation seeks to answer must be at a minimum. This begins by narrowing the list of ‘stakeholders’ of the evaluation down as much as possible and let their request be the basis for the focus of the evaluation. By doing this it is avoided that stakeholders have different perception of the evaluation because they are interested in different things (Patton, 1997). 2.2 Public benchmarking Public benchmarking is the predominant in public sectors. It is a compulsive systematic measurement and comparison of performance driven by an external agency (e.g. the government). Indicators from the benchmarking system are utilized to support the external agency in decision making and judging the success of those being measured on performance (Triantafillou, 2007). Public benchmarking is useful in clarifying whether a provider of a product or a service compares well against competitors. Only little focus is given to the processes leading to the results (Bowerman et al. 2001).The external agency is the intended user of the benchmarking system and the results are used to regulate, control and monitoring those being measured on performance. Benchmarking in the public sector can ‘[…] be seen as a form of power that depends on the capacities of organizations to govern themselves in a proper manner’ (Triantafillou, 2007, p. 831). It becomes a powerful tool for the external agency to create incentives in market areas where the competition is inexpedient, rationalization is not naturally provided or more transparency is requested (KonkurrenceStyrelsen, 1998). Benchmarking indicators become synonymous with the ambitions of success set up by the external agency, thus, activating individuals and organizations to seek equivalent ambitions (Triantafillou, 2007). From the evaluation theory Dahler-Larsen (2008) characterizes it as control when indicators are exposed to judgment and used by an external agency for decision making. The primarily focus is on the process of measuring and the results from the evaluation. The evaluation becomes a tool for the external agency to control, monitor and regulate another public agency. Often external agency is not concerned with the effects the regulation has had on other parts of the system (Dahler-Larsen, 2008; Andersen, 2004). It should be emphasized that, the control use does not necessarily counteract learning and improvement (Dahler-Larsen, 2008). If formulated sufficient, the same set of indicators can be use for several purposes. Patton (1997) calls it judgment-oriented evaluation when evaluation results are used to determining worth or value of something. The intended user of the evaluation is the external agency who uses the results to decide whether the program is satisfactory or not. Evaluation results are used to judge efficiency and quality and to create comparative rating or rankings of programs (Patton, 1997). Measures in judgment-oriented evaluation are highly maintained, to make comparability of performance possible over a longer period of time, hence, the most critical and central part of judgment-oriented evaluation is specifying the criteria for judgment. 2.3 Public benchmarking vs. best practice benchmarking An analogy by Scriven (in Patton, 1997, p. 69) gives us a suitable distinction between improvement- and judgment-oriented evaluation, comparable with the distinction between public benchmarking and best practice benchmarking: ‘When the cook tastes the soup, that’s formative; when the guests taste the soup, that’s summative.’ Patton (1997, p. 69) explicate this quote as follows: ‘More generally, anything done to the soup during preparation in the kitchen is improvement-oriented; when the soup is served, judgment is rendered, including judgment rendered by the cook that the soup was ready for serving (or at least that preparation time had run out.)’. In the context of this paper, the guests obliviously represent the external agency and the cook represents the organizations or individuals being benchmarked. This separation in who is rendering judgment (the guest or the cook) could help clarifying how improvement is expected to follow in the wake of benchmarking when using the two types of benchmarking. When the soup is served to the guests, the cook (might) get feedback from the guests on his/her performance. In the long term, a plausible effect could be that the cook gets better in knowing the criteria the guests use to judge the soup, hence, making suitable modifications using the time and ingredients available. Following this line of metaphors; if the cook tastes the soup and renders judgment, he/she makes use of own expertise, expectations and success criteria, hence continuously modifying the soup during the process of preparation. This may or may not result in an acknowledgement of needing higher professional competences in the kitchen, new ingredients to change the content or more efficiency during the preparation of the soup. When used formative, performance of the provider is judged. When the judgment has consequences for the provider it becomes an element in regulating the provider to meet the expectations of the judge. When judgment is used summative, improvement is possible during the process and becomes an element for the provider to achieve better processes. Table 1: A summary of the distinctions between the two benchmarking types Public benchmarking Best practice benchmarking Sphere Public sector Private sector Evaluation term Summative, judgment-oriented Formative, improvement-oriented Intended users External agency The market/companies View Outside view on performance Inside view on processes Benchmarking affiliation Compulsive Voluntary Measuring process Retrospective (after completion) Ongoing Expected benefits Provides basis for decision, identifies best in class, regulates, controls, monitoring, explicate success criteria and target setting Provides learning of best practices, mutual benefits to participants, continuous improvement of processes Risk Limited learning for others than the intended users, limited process improvement Many interests, fragile due to participation requirements (e.g. collaboration, dedication, involvement and trust), difficulties in benefit every participant equally 3. Benchmarking in the Danish construction sector Change in construction is high on the agenda for the Danish government and a comprehensive effort is being made to achieve high quality and efficiency (The Danish Government, 2003). This discourse of changes in the Danish construction sector is a phenomenon that doesn’t differ much from the reform movement in the UK. The motives to initiate the changes are almost equivalent to the areas of weakness described by Latham (1994) and Egan (1998). Inspiration has been drawn from the UK and during the recent years the concept of benchmarking has been gaining ground in the Danish construction sector. Since January 2004 the Danish government has made benchmarking of Danish state construction projects and social housing projects (since marts 2007) compulsory when the contract sum exceeds 5 million DKK (~ 1 million USD). Project information is reported in the beginning of the construction project and performance information shortly after hand-over. The performance information is transformed into indicators in the following categories; customer satisfaction, defects, compliance with time schedule and accident frequency at the workplace (http://www.byggeevaluering.dk). There are no demands for ongoing reporting of information during execution of the project. An additional requirement is that, contractors bidding for Danish state construction projects and social housing projects must substantiate their capabilities in form of indicators/results from previous construction projects. These are used by state clients to prequalify contractors. The legal requirements evoked new demands in measuring the performance in the construction sector. As a result of this, the Benchmark Centre for the Danish Construction Sector (BEC) was established in 2002. BEC was formed by several organizations in the construction sector including the National Agency for Enterprise and Construction. BEC was established with the purpose of providing the necessary service to meet the governmental requirements for benchmarking the construction sector (The Danish Government, 2003), and to create a national benchmarking system that could benefit the private sector as well. The origin objectives of the benchmarking system was to enhance transparency in the market concerning the relationship between price and quality (The Danish Ministry of Economic and Business Affairs, 2008) and improvement of quality and efficiency within the construction sector through competition and learning. Today the target groups are primarily construction clients. Since its establishment in 2002 BEC has extracted information from more than 1600 building contracts divided among more than 500 building projects. BEC primarily focuses on customizing and promoting their product to Danish construction clients in order to make them use the benchmarking results in prequalification of contractors. Since the implementation of the benchmarking system 60 % of the construction projects have been benchmarked on a voluntarily basis (projects not subjected to the governmental demands). There has been only little use of the data collected by BEC in the creation of best practices. BEC has recorded an increasing interest from contractors for indication of their companies marked position. 4. Challenges in benchmarking the construction sector Before considering the benchmarking characteristics and objectives of the Danish benchmarking efforts, it is relevant to be reflective about the reality that surrounds the benchmarking system. It should be taken into consideration, that implementing and framing a complete benchmarking system for the construction sector is a challenging task. This is often argued to be caused by the characteristics that distinguish the construction sector from other industrial sectors. Some of the barriers most commonly pointed out is that the construction sector is project based and the projects are temporary, short-term, complex and with many changing participants each having different criteria of project success (e.g. The Danish Government, 2003; Costa et al., 2004; Chan and Chan, 2004; Lee et al., 2005; Lin and Shen, 2007). This leaves a comprehensive task in providing a benchmarking system that fulfills the demands of best practice benchmarking; meeting the interests of each participant and measuring on methods, processes and practices during the project period (Lin and Shen, 2007). This in mind, it should also be taken into consideration that the Danish contractor companies are known to be very conservative to changes (Dræbye, 2003). Focusing on the barriers and interest of implementing benchmarking in construction companies, it is interesting to note, that a research of four different benchmarking initiatives for construction from Brazil, Chile, the UK and the USA, concludes that many construction companies have difficulties getting involved on a permanent basis (Costa et al., 2004). The same research identifies that the main interest of construction companies to get involved in benchmarking initiatives is to compare their performance against other companies. 5. Appraisal of the effort in benchmarking the Danish construction sector ‘What gets measured gets attention, particularly when rewards are tied to the measures’ (Eccles, 1991). Comparing the Danish benchmarking system to best practice benchmarking (the inside view on processes), the system falls short; the contractors are not provided any learning about methods, practices and processes used by others. Best practice benchmarking is encouraged by trust, collaboration and mutual benefit leading to continuous improvement of processes leant for others (Watson, 1993; Camp, 1995). The critical characteristics of the Danish benchmarking system are limited to competitive comparison of contractors for contractor selection. There is no measuring or initiated research towards an understanding of the processes leading to the results of superior performance of contractors, indicating a high degree of public benchmarking. This competitive and controlling use of results is undermining the intensions of sharing knowledge of processes leading to superior performance (Camp, 1995; Dahler-Larsen, 2008). This development could be an outcome of what Dahler-Larsen (2008) and Patton (1997) emphasize as; the erroneous in evaluating on interest of others than the intended users. Addressing benchmarking from this perspective, the intensions of an overall improvement of quality in the sector using best practice benchmarking (with contractors being the intended users) is in contradiction to utilization of indicators for contractor selection (with clients being the intended users). An important factor in this conflict of interest could be caused by the government’s role; the government determined the objectives of the benchmarking system when initiating benchmarking in the construction sector, hence benchmarking has become a way to visualize the target of government ambitions, causing the private market to act with ‘a responsibility for the governing of a particular field or set of activities’ (Triantafillou, 2007, p. 836). Dahlberg and Isaksson (1996, p. 36) point out that; ‘[t]his “outsider” effect can represent a challenge for the development of a benchmarking culture within the agencies concerned. This “ownership” aspect of the benchmarking process can substantially influence attitudes towards the concept of “learning from others”’. As a result of the government’s role (as external agency), and the clients being intended users of indicators for competitive comparison, the benchmarking system is insufficient in content of information that are useful for contractors to learn from each other in order to improve their performance. Ownership, involvement, reflection and relevance are lacking in the objectives of providing best practice benchmarking for contractors. The governmental long term desire for achieving quality and efficiency in the construction sector trough learning from the practices of others are overlooked in favor of the intensions of the clients and the government. As emphasized by Dahler-Larsen (2008), results of an evaluation must make sense and be useful to those responsible for the improvement process. The clients and the government have increasingly become the intended users of the benchmarking system, using it as a regulation tool driving contractors towards achievement of good results in order to compete in the prequalification in future projects. The benchmarking results provide transparency of the sector within the areas defined by the government. It could be interpret as a positive and successful development of the interest in benchmarking that 60 % of the construction projects are conducted on a voluntarily basis. It is evident that the stakeholders of the benchmarking system have been narrowed down, which is a positive tendency for a benchmarking system, since it is crucial not to have too many intensions with the same system (Patton, 1997; Dahler-Larsen, 2008). But it is also evident that the adjustments have not favored the contractors in the objectives of best practice benchmarking; the benchmarking system primarily profits the clients (for contractor selection) and the government (for regulation and monitoring) leaving no more than competitive performance comparison to the contractors. (Luckily) Costa et al. (2004) identified comparison of performance as the main interest of contractors to get involved in benchmarking. The underlying reason to the decreasing number of stakeholders could be found in the problematic in framing a complete benchmarking system beneficial to every participant involved a construction project (Costa et al., 2004; Chan and Chan, 2004; Lee et al., 2005). It may be this challenging element in benchmarking the construction sector that creates a tension field between compulsive comparison and voluntarily process improvement of contractors, leading to a necessity in narrowing down the stakeholders and the intensions for benchmarking. These tendencies have occurred in Denmark, making the clients and the government the intended users and the governmental intensions dominate the use and scope of benchmarking. The outcome of the development is limited to a gathering of information that can be translated into something measurable (indicators) which clients can use for contractor selections and the government for monitor and regulate the construction sector. 6. Discussion The compulsory element in benchmarking the Danish construction sector has led to a substantial amount of comparable indicators, but there are important considerations to be made, when using the indicators in the perception of public benchmarking. Setting up the indicators for a benchmarking system, the diversity in perception of project success is evened out across the project participants. This arises a problem, since project success varies significantly according to whom is defining success (Dahler-Larsen, 2008) and particular in the construction sector (Chan and Chan, 2004; Lee et al, 2005). Unintended effects are in the risk of emerging when focusing and rendering judgment based exclusively on the governmental fixed indicators. Indicators often become (intentional or unintentional) a determination and reflection of the problem areas, identifying where success is rendered or where improvement is needed. They help capturing and translating something complex to numbers which allow decisions to be made at a distance. The indicators become a view of the performance of contractors through the eyes of the government and the clients. The governmental identification and visualization of problem areas through indicators, constructs a prevalent comprehension of the problems dominating the sector. This could make the ability of judging and visualizing the problem areas more important than improving of the processes construction the problem areas. Dahler-Larsen (2008) uses the term indicator fixation as a concept for having too much focus on a set of indicators. He uses the concept to emphasize an effect often followed in the wake of the establishment of indicators; the construction of a simplification of excellence. The indicators risk become the definition of quality and project success, hence becoming targets themselves and could influence the self-understanding and attitudes of those exposed to judgment based on their performance indicators. ‘The emergency rooms in England had problems with patients being on waiting lists for a long time. Accordingly a quality system was implemented in order to measure the time it took from a patient entered the emergency room until he or she was contacted by healthcare personnel. As a result, the hospitals hired so called ‘hello-nurses’, with the job function simply to approach incoming patients and say ‘hello’’ (translated from Dahler-Larsen, 2008, p. 19). This story reveals that unintended effects are in risk of emerging, if measures are becoming the definition of quality and meanwhile deficient described. If the indicators in a benchmarking system are a poor reflection of what they try to capture, it generates a risk in other elements being unintended affected in the quest of fulfilling the criteria best possible. Inadequate indicators could end up influencing the action of those being measured, leaving a dichotomy of the comprehensions of success; is success achieved through well executed processes or through a fulfilling of the criteria set up in the indicators? This stresses the point that when consequences are attached to indicators, the determination of them is the most crucial element in benchmarking. The indicators must be able to answer the right questions as well as answering the questions right. The actual effects of the benchmarking in the Danish construction sector will remain unanswered in this paper. The only certainty is that benchmarking always has effects. 7. Conclusions The governmental efforts in bringing benchmarking into the Danish construction sector have been discussed. It has been attempted to widen the theoretical spectrum of benchmarking in construction by supplementing the discussion with elements of public benchmarking and utilization focused evaluation theory. The benchmarking efforts in the Danish construction sector have been discussed using two distinct perceptions of benchmarking; public benchmarking and best practice benchmarking. In conclusions it has been argued that construction clients and the government are the intended users of the benchmarking system. The benchmarking results are primarily used by clients for contractor selection and the government for monitoring and regulation of the construction sector. This is argued to undermine the intentions of distributing best practice and voluntary knowledge sharing among contractors. In closing, reflection of possible effects and risks of the present use of benchmarking in the Danish construction sector has been laid out. It has been emphasized that unintended effects may follow in the wake of using benchmarking to define success and judge the performance of contractors, hence constructing an overall comprehension of what constitutes project success in the construction sector. References Andersen, S. C. (2004), “Hvorfor bliver man ved med at evaluere folkeskolen”, Politica, Vol. 4, p. 452-68 Beatham, S., Anumba, C., Thorpe, T. and Hedges, I. (2004), “KPIs: a critical appraisal of their use in construction”, Benchmarking: An international Journal, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 93-117 Bowerman, M., Ball, A. and Francis, G. (2001), “Benchmarking as a tool for the modernisation of local government”, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 17, No. 4 Bowerman, M.; Francis, G.; Ball, A. and Fry, J. (2001), “The evolution of benchmarking in UK local authorities”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 429-449 Camp, R. C. (1989), “Benchmarking. The search for Industry Best Practices that Lead to Superior Performance, part I” Quality Progress, pp. 61-68 Camp, R. C. (1995), Business Process Benchmarking: Finding and Implementing Best Practices, ASQC Quality Press, Milwaukee, WI Chan, A. P. C. And Chan, A. P. C. (2004), “Key Performance Indicators for measuring construction success”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 203-221 Chen, H.L. (2005), “A competence-based strategic management model factoring in key success factors and benchmarking”, Benchmarking: An international Journal, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 364 Costa, D. B.; Formosco, C. T.; Kagioglou, M.; Alarcón, L. F. (2004), “Performance Measurement Systems for Benchmarking in the Construction Industry” In: Conference on the International Group for Lean Construction, 12., 2004, Helsingor. Proceedings IGLC-12, 2004. pp. 451-463. Cox, J.; Mann, L. and Samson, D. (1997), “Benchmarking as a mixed metaphor: disentangling assumptions of competition and collaboration”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 285-314 Dahlberg, L.I., Isaksson, L. (1996), "The implementation of benchmarking from a Swedish perspective", in Trosa, S. (Ed), Benchmarking, Evaluation and Strategic Management in the Public Sector, OECD, Oxford Dahler-Larsen, P. (2008), Konsekvenser af indikatorer, Krevi, Aarhus, Denmark Dawkins, P., Feeny, S. And Harris, M.N. (2007), “Benchmarking firm performance”, Benchmarking: An international Journal, Vol. 14 No. 6, pp. 693-712 Dræbye, T. (2003), ”Implementering af Det Digitale Byggeri” Erhvervs- og Boligstyrelsen, Copenhagen, Denmark Eccles, R.G. (1991), “The Performance Measurement Manifesto”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 69 No. 1, pp. 131-7 Egan, J. (1998), Rethinking Construction: Report of the Construction Task Force on the Scope for Improving the Quality and Efficiency of the UK Construction Industry, Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, London El-Mashaleh, M. S., Minchin, R. E. And O’Brien W. J. (2007), “Management of Construction Firm Performance Using Benchmarking”, Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 10-17 Fernie, S.; Leiringer, R and Thorpe, T. (2006), “Change in construction: a critical perspective”, Building Research and information, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 91-103 Haugbølle, K., Hansen, E. (2006), “A typology of benchmarking systems”, Construction in the XXI century: Local and global challenges: Proceedings of the Joint International CIB W055/W065/W086 Symposium Construction in the 21st century, Napoli, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane KonkurrenceStyrelsen (1998), “Redegørelse om benchmarking”, KonkurrenceStyrelsen, Copenhagen, Denmark Latham, M. (1994), Constructing the Team: Joint Review of Procurement and Contractual Arrangements in the UK Construction Industry, HMSO, London. Lee, S.; Thomas, S. R.; Tucker, R. L., (2005), “Web-based Benchmarking System for the Construction Industry”, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 131, No. 7, pp. 790-798 Lin, G.; Shen, Q. (2007), “Measuring the Performance of Value Management Studies in Construction: Critical Review”, Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 2-9 Moriarty, J.P. and Smallman, C. (2009), “En route to a theory of Benchmarking”, Benchmarking: An international Journal, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 484-503 Patton, M.Q. (1997), Utilization-focused evaluation: The new centery text (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Scriven, M. (1991), “Beyond Formative and Summative Evaluation”, Evaluation and Education: At quarter century, Edited by M. W. McLaughlin & D.C. Philips. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 19-64 The Danish Government (2003), Staten som bygherre – vækst og effektivisering i byggeriet, Denmark The Danish Ministry of Economic and Business Affairs (2008), Vejledning om nøgletal for statsligt byggeri m.v., Denmark Triantafillou, P. (2007), “Benchmarking in the public sector: A critical conceptual framework”, Public Adminstration, Vol. 85, No. 3, pp. 829-846 Watson, G.H. (1993), Strategic Benchmarking: How to Rate Your Company’s Performance against the World’s Best, Wiley, New York, NY Zairi, M. (1997), “Benchmarking: towards being an accepted management tool or is it on its way out?”, Total Quality Management, Vol. 8, Nos 2/3, pp. 337-8