Individual Report on the UN General Assembly and the Human

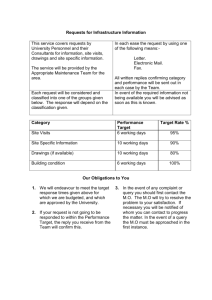

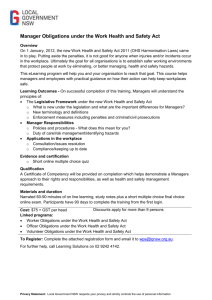

advertisement