Understanding quality in child care: Identifying international

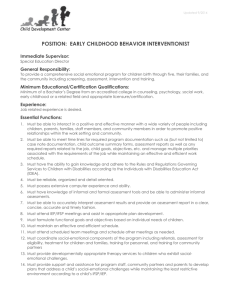

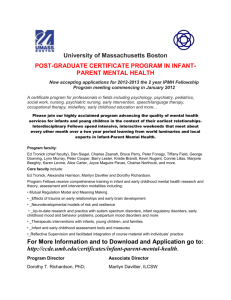

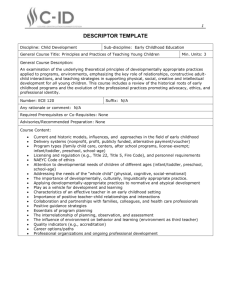

advertisement