Alternative Basic Education - Institut für Bildungswissenschaft

advertisement

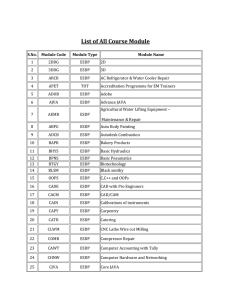

1 Present Status and Challenges of Education for all in Ethiopia Tirussew Teferra, Professor & Laureate in Education Addis Ababa University Jyvaskula , Finland November 17-19, 2011 2 1. Introduction Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa (estimated around 80 million, of which approximately 12 million are pastoralists and 80 percent of the population live in rural areas), and has a decentralized government structure. In Ethiopia, primary education lasts 8 years and is split into grades 1-4 (primary first cycle) and grades 5-8 (primary second cycle). Secondary education is also divided into two cycles, each with its own specific goals. Grades 9-10 (secondary first cycle) provide general secondary education and, upon completion, students are streamed either into grades 11-12 (secondary second cycle) as preparation for university, or into technical and vocational education and training (TVET), based on the performance in the secondary education completion certificate examination. General education comprises grades 1 to 12. The provision of education is the concurrent responsibility of federal, regional and local governments. The Federal Government plays the dominant role in the provision of postsecondary education, while also setting standards and providing overall policy guidance and monitoring and evaluation for the entire sector. Regional governments are responsible for the oversight of the training of primary school teachers, for providing primary textbooks and for adapting the primary syllabus to local conditions. Woreda (district) governments are responsible for paying and recruiting primary and secondary teachers, and for supervision and training of primary and secondary teachers (World Bank, 2008). The Education and Training policy, (TGE, 1994), was the initial policy document that set the year 2015 as the target for achieving the goal of good quality universal primary education. This policy has introduced major changes and reforms to address the country’s educational problems. 3 The education sector programs are sector-wide and covers all levels and areas of education, all tiers of governments and all forms of expenditures. The duration of the programs is designed to be 20 years (1997-2016) with four consecutive phases. The basic aims of the programs is “increasing access, improving quality, increasing effectiveness, achieving equity and expanding finance at all levels of education within Ethiopia” (Checkole K, 2004) . The first Education Sector Development Progr am (ESDP I) was launched in 1997 within the framework of the Education and Training Policy to cover the period 1997/98- 2001/02. The Government later developed a comprehensive Five Year Education Program 2000/012004/05, aligned with the five year term of the government. ESDP II had also to be aligned with that program and had as a result only three years 2002/03 to 2004/05 The ESDP III is now synchronized with the Government’s five year planning cycle and covers the period 2005/062010/11 ( Ministry of Education, 2008).During ESDP III (2005/06-2010/11) access at all levels of the education system increased at a rapid rate, in line with a sharp increase in the number of teachers, schools and institutions. There were improvements in the availability of trained teachers and some other inputs which are indispensable for a quality education system. Sound improvements were observed in the education of the disadvantaged and deprived groups and of the emerging regions. Furthermore, efforts were made to make the content and the organization of education more relevant to the diversified needs of the population, for instance through the introduction of alternative basic education and the development of innovative models such as mobile schools. Woreda education offices and communities have strengthened their involvement in education planning, management and delivery. Strategies were developed for (Alternative for Basic Education (ABE), Early Childhood Care and Education ( ECCE) and Functional Adult Education (FAL), and new school health and nutrition initiatives were launched (ESDP IV, 2011/2012). 2. Status of EFA in Ethiopia In the following section attempt is made to highlight the achievements made mainly focusing on the Six EFA Goals in Ethiopia. The data is heavily dependent on the Education Statistics Annual Abstract of the Ministry of Education, 2010, Ethiopia. 4 2.1 Goal 1: Early Childhood Care and Education This goal relates to the expansion and improvement of comprehensive early childhood care and education for all children. It is aimed at making ECCE accessible to all children of the appropriate age group (age 4-6) with out any form of discrimination (UNESCO, 2011). In Ethiopia, in the year 2008/09 out of the estimated 6.95 million children of the appropriate age group (age 4-6) only about 294,767 children have been reported to have access to ECCE centers all over the country. Though the enrollment is small when compared to the appropriate age group, enrollment is higher than the previous year by about 11.0%. Moreover, since the data at this level does not cover all schools (data from some NGOs and faith-based schools are not captured) total enrollment could be higher than the figure indicated. . The Gross Enrollment Rate for ECCE in the year 2008/09 is 4.2% which is very daunting (Ministry of Education,2010). Table 1: ECCE gross enrollment Year 1996/97 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 AAG* Enrollment - 153,280 186,728 219,068 263,464 292,641 17.5 ECCE centers - 1,497 1,794 2,313 2,740 2,893 17.9% MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) * Annual Average Growth 2.2 Goal 2: Universal Primary Education This is ensuring that by 2015 all children, particularly girls, children in difficult circumstances and those belonging to ethnic minorities, have access to and complete, free and compulsory primary education of good quality (UNESCO, 2011). 2.2.1 Primary School Enrollment Table 2: Growth of primary schools in the last five years Year 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 AA G* Primary 16,513 19,412 20,660 23,354 25,212 11.2% MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) * Annual Average Growth 5 An impressive growth of primary schools is observed in the last five years in Ethiopia, however, there are still large class sizes and shift systems across regions. Table 3: Gross enrollment rate (GER) at primary level (1-8) Primary 1st Year Cycle (1-4) (%) Primary 2nd Cycle (5-8) (%) Boys Girls Total Boys Girls Total Boys Girls Total 2004/05 109.8 95.5 102.7 62.0 42.6 52.5 88.0 71.5 79.8 2005/06 123.9 111.2 117.6 67.4 49.8 58.8 98.6 83.9 91.3 2006/07 122.9 111.2 117.1 68.3 53.7 61.1 98.0 85.1 91.7 2007/08 133.0 122.5 127.8 64.8 55.5 60.2 100.5 90.5 95.6 2008/09 126.7 118.4 122.6 65.6 60.5 63.1 97.6 90.7 94.2 Year Primary (1-8) (%) MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) The GER has shown drastic change in the last five years with the exception of 2007/08 with a minor decrease. An increase in Gender Parity Index (GPI) is also observed ranging from GPI 1 to 0.76 in the last five years. Indicating the improvement from no gender disparity to a relatively low gender disparity. The following table depicts the gender disparity observed across regions. Table 4: Gross enrollment rate by region and gender Gender/Region Male Female Total Tigray 95.6 % 98.1% 96.9 % SNNP* 94.3 % 84.5 % 89.4 % Afar 25.3 % 23.2 % 24.4 % 6 Gambella 80.2 % 69.7 % 75.2 % Amhara 101.4 % 103.1 % 102.2 % Harari 100.2 % 83.6 % 91.9 % Oromia 80.9 % 74.8 % 77.9 % Addis AbabA 78.2% 74.4% 76.1% Somali 33.3 % 29.4 % 31.6 % Dire Dawa 76.5 % 70.2 % 73.4 % Benishangul-Gemuz 97.0 % 80.1 % 88.6 % Total 84.6 % 81.3 % 83.0 % MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09 *SNNP Southern Nations ,Nationalities & Peoples Table 4: Net enrollment rate (NER) at primary level (1-8) Grade/Year Primary 1st Cycle (1-4) (%) Primary 2nd Cycle (5-8) (%) Primary (1-8) (%) 2005/06 73.0% 37.6% 68.5% 2006/07 79.9% 39.4% 77.5% 2007/08 90.1% 39.9% 79.1% 2008/09 88.7% 46.0% 83.4% AARG - - 4.9% MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) NER is the best way of measuring organized on-time school participation and is a more refined indicator of school and enrollment coverage in terms of explaining the proportion of students enrolled from the official age group. NER is calculated by dividing the number of properly aged primary students (for Ethiopia ages 7-14) by the number of children of school going age (7-14). NER is usually lower than the GER since it excludes over-aged and under-aged pupils (MoE, 2010). 2.2.1.1 Enrollment of children with special educational needs According to the data available, the total number of students with special educational needs in 2008/09 in primary (Grades 1-8) is around 41,509. This is nationally insignificant figure compared to number of primary school-age children with disabilities in the country. The following table desegregates students with disability served in primary schools by type of disability and gender. Table 4: Enrollment of children with special educational needs 7 Primary 1-8 Type of disability Male Female Total Visual Impairment 4,034 2,777 6,811 Physical/Motor Impairment 8,516 6,075 14,591 Hearing Impairment 5,061 3,666 8,727 Intellectual Disability 5,323 3,856 9,179 Total 24,142 17,367 41,509 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) As can be noted from the Table above the participation rate of girls with disability is lower than that of boys with disabilities. 2.2.2 Secondary School Enrollment The table below depicts, the steady growth rate of the secondary schools in the last five years. Table 7: Growth of secondary schools in the last five years Year Secondary 2004/05 706 2005/06 835 2006/07 952 2007/08 2008/09 1,087 1,197 AA G 14.1% MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) Table 8: Net enrollment rate (NER) at secondary education Level/Year General Secondary1st Preparatory 2nd Cycle (11- Cycle (9-10) 12) Secondary Education (9-12) 2004/05 860,734 92,483 953,217 2005/06 1,066,423 123,683 1,190,106 2006/07 1,223,662 175,219 1,398,881 2007/08 1,308,689 193,444 1,502,133 2008/09 1,383,946 205,261 1,589,207 AARG 12.6 22.1 13.6 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) Table :Gross enrollment ratio by gender at secondary education level (9-12) General Secondary, 1st Cycle (9-10) 8 Preparatory 2nd Cycle (11-12) Enrollment Ratio % Enrollment Ratio % Boys Girls Total Boys Girls Total 2004/05 34.6 19.8 27.3 4.3 1.7 3.0 2005/06 41.6 24.5 3 33.2 5.7 2.0 3.9 2006/07 45.7 28.6 37.3 7.3 3.7 5.5 2007/08 44.4 29.6 37.1 7.8 3.8 5.8 2008/09 43.7 32.4 38.1 8.5 3.5 6.0 AAG 9.7 17.2 12.6 21.4 23.7 22.1 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) Gender Parity Index (GPI) for first cycle secondary education (grades 9-10) shows that GPI for 2008/09 is 0.74 and for the second cycle (grades 11-12) is 0.41. This indicates that the number of girls joining preparatory is smaller than that of boys. The pattern in the second cycle of secondary will obviously affect the gender gap in tertiary education. 2.3 Goal 3 & 4: Learning Needs of Young People and Adults & Improving levels of Adult Literacy These two goals complement and ensure that the learning needs of all young people and adults are met through equitable access to appropriate learning and life skills programs. It is aimed at achieving a 50 per cent improvement in levels of adult literacy by 2015, especially for women, and equitable access to basic and continuing education for all adults. Governments have mainly responded to the learning needs of young people and adults by expanding formal secondary and tertiary education. However, a great variety of structured learning activities for youth and adults takes place outside formal education systems, often targeting school dropouts and disadvantaged groups. Improved monitoring of the supply and demand for non-formal education is urgently needed (UNESCO, 2008). The ESDP III (2005/2006- 2010/2011) specifically discusses the adult and non-formal education program and defines it to include a range of basic education and training components for out-ofschool children and adults. The action plan defines the content of the adult and non-formal 9 education to include literacy, numeracy and the development of skills that enable learners to solve problems and to change their lives. The action plan also outlines three sub-component modes of delivery for adult and non-formal education (Anis,2007) : 1) Alternative basic education for out-of-school children between the ages of 7-14 2) A functional adult literacy program for youth and adults over 15 and 3) Community skills training centers for youth and adults . The Ethiopian Government set the target of reaching 5.2 million adults between 2005-201 through functional adult literacy and 143,500 adults through the nation’s existing 287 Community Skills Training Centers (CSTCs). In the Education Sector Development Plan III, the Government committed itself to develop an equivalence system between skills gained through non-formal education and those gained through formal education. The Government has also adopted alternative basic education as a strategy to increase enrollment and ensure greater equity for “disadvantaged children including girls, children with special needs, and children from pastoralist, semi-agriculturalist and in isolated rural areas” (Ministry of Education, 2005 in Anís, 2007) 2.3.1 Alternative Basic Education (ABE) In order to realize the goal of universalizing access to primary education by 2015, ESDP IV envisaged provision of basic education through alternative modes. Accordingly, in the last two to three years, in specific regions ABE centers were established. Most ABE activities are accomplished in Basic Education Centers, and are designed to enroll the same age group as regular primary education. Since 2005-06, ABE enrollment has been included in the reporting of the regular education—and therefore GER and NER reflect the contribution of ABE to primary education in Ethiopia. The following table depicts the pattern of ABE centers by year and gender. Table 10 : Alternative Basic Education (ABE) Year/Gender Male 2004/05 250,243 2005/06 426,036 2006/07 311,427 10 2007/08 349,863 2008/09 422,512 AAGR 14.0% Female 491,515 391,296 271,339 287,380 357,830 Total 741,758 817,332 582,766 637,243 780,342 -7.6% 1.3% MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) 1 2.3.2 Adult & non-formal education Adult and non-formal education is designed to address the primary education needs of adults and others who are substantially older than the traditional primary school going ages of 7-14. Data capturing these programs, as acknowledged by the Government are comparatively new in Ethiopia, and reporting accuracy is very uneven-both because many such programs are operated by non-government entities, and because many regions are not yet fully sensitized to the role of this type of education (Minstry of Education,2010). Table 11: Adult non-formal basic education enrollment by gender & region Gender/Region Male Female Total Tigray 830 830 1660 SNNP 6,196 4,813 11,009 Afar 23 7 30 Gambella 277 276 5,530 Amhara 3,807 1,798 5,605 Oromia 77,863 3,8052 115,915 Addis AbabA 6,949 1,4804 21,753 Total 95,998 60,590 156,588 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) According to the above data, adult and non-formal education program run by government and non-governmental organizations are predominantly in Oromia and Addis Ababa predominated (MoE,2010). The ESDP III notes that the adult and non-formal education program includes a range of basic education and training components for out-of school children and adults and that it is basically focused on literacy, numeracy and other relevant skills to enable learners to develop problem-solving abilities and change their lives. It is explained in the situation analysis of ESDP III that the CSTCs offer specific learning skills related to the specific needs of the rural 11 community and prepare the community to participate efficiently in the development activities and to upgrade and improve the traditional rural skills. ESDP III recognizes that government alone cannot provide sufficient financial or human resources to support the program and hence will seek support from other stakeholders: multi-lateral and bilateral development partners, NGOs, local governments and communities (Ministry of Education, 2008). The role parents can play in promoting primary school completion rate, improving quality education and increasing gender-parity in primary education in Ethiopia is underlined by ESDP III. 2.4 Goal 5: Gender parity and equality Eliminating gender disparities in primary and secondary education by 2005, and achieving gender equality in education by 2015, with a focus on ensuring girls’ full and equal access to and achievement in basic education of good quality. The Dakar Framework for Action set bold targets for overcoming gender disparities, some of which have already been missed. Even so, there has been progress across much of the world in the past decade. Viewed from a global perspective, the world is edging slowly towards gender parity in school enrolment. Convergence towards parity at the primary school level has been particularly marked in the Arab States, South and West Asia and sub-Saharan Africa – the regions that started the decade with the largest gender gaps (UNESCO,2008). At Dakar forum it was agreed that the necessary first step towards the goal was to bring about parity of enrolments, and beyond that there was a wide consensus on the importance of a number of measures to ensure retention, completion and satisfactory attainments ( International Working Group on Education,2003). Gender disparities have been reduced in primary education, but not eliminated. In Africa only Mauritius and Seychelles had achieved gender parity in their GERs for both primary and secondary education by 2005.Gender disparities remain widespread in sub-Saharan Africa where they often favor boys, and are greater at higher levels of the educational ladder: According to 35% of the countries whose data available in 2005 had achieved gender parity in primary education, compared with 6% in secondary and 3% in tertiary (UNESCO, 2008). 12 As indicated in the forgoing discussion, Ethiopia has demonstrated an impressive improvements gender parity in primary education but there is still a notable gender disparity in secondary and higher education . Furthermore, evidences suggest that the participation of females in ABE and adult and non-formal basic education is lower than males. 2.5 Goal 6: Quality of education Improving all aspects of the quality of education and ensuring excellence of all so that recognized and measurable learning outcomes are achieved by all, especially in literacy, numeracy and essential life skills (UNESCO.2011). Evidences suggest that there are several indicators of quality education and others the following are most frequently mentioned in several international documents include: teachers’ qualification, pupils-teacher ratio, learning and school environment, amount of instructional time and learning outcomes. 2.5.1 Pupil-teacher ratio (PTR) Pupil teacher ratio is one of the common education indicators for efficiency and quality. However, there are two views on PTR, namely: a) The lower the PTR the better the opportunity for contact between the teacher and pupils for the teacher to provide support to students individually, thereby improving the quality of education. This indicator is useful for setting minimum standards throughout the country-and ensuring a certain level of equality around the country. In Ethiopia, the standard set for the pupil/teacher ratio is 50 pupils per teacher at primary (1-8) and 40 pupils per teacher at the secondary level. As per the report of the Ministry of Education Statistical Abstract (2008/09) indicates that PTR is closer to national standard, which is about 4 percentage points above the national standard of 50 pupils per teacher., However, large class sizes and practices of shift systems are still in place both in primary and secondary schools. 2.5.2 Learning Achievements Since 2000, countries have increasingly conducted national learning assessments; in sub-Saharan Africa, the percentage of countries that carried out at least one national assessment between 2000 13 and 2006 was 33%. The national assessments focus more on grades 4 to 6 than on grades 1 to 3 or 7 to 9, and are predominantly curriculum-based and subject-oriented, in contrast to international assessments, which focus on cross-curricular knowledge, skills or competencies. (UNESCO, 2008). In some areas, quality has deteriorated at least partly as a result of rapid expansion. For instance, The Ethiopian National Learning Assessment showed that the mean score for all subjects of grade 4 and grade 8 students declined from 48.48% and 39.74% respectively in 2004 to 39.8% and 36.6% respectively in 2007 (ANFEAE, 2008).The decline in quality and the decreasing trend of students’ performance might therefore be attributed to multiple factors including those discussed under this section. 2.5.3.1 Primary school teacher’s qualification Table 12: Primary school teachers’ qualification Teachers” Qualification (%) Year/Cycle 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 1st Cycle 97.1 97.6 96.3 97.3 89.4 Male 96.5 97.2 96.4 97.0 90.8 Female 57.4 62.6 56.8 72.5 76.8 2nd Cycle 54.8 59.4 53.4 66.3 71.6 Male 54.2 58.6 52.2 64.1 69.6 Female 57.4 62.6 56.8 72.5 76.8 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) Generally, the qualification of teachers in the first cycle is very impressive with the exception of the year 2008/09.From the above Table, it encouraging to note that the number of female qualified teachers exceed from that of males in the second cycle but the males surpass females. This should be subject for further investigation. 2.5.3.2 Secondary school teachers’ qualification y S The qualification, motivation and availability of teachers are important quality measures. In contrast with primary education overall, the percentage of qualified teachers is lower in 14 secondary education. Nationally only 75.2% of all secondary teachers are qualified for their level of teaching. Although we do not yet have exact statistics, it is likely that preparatory cycle (Grade 11-12) teachers may be even less qualified for their level than those teaching first cycle (Grade 9-10). As Chart 4.21 quite clearly shows, Tigray, Dire Dawa, Addis Ababa and Amhara had the better percentage of qualified teachers which is above the national average. There is no gender disparity nationally; but there appear to be significant disparity in Somali and Beneshangul gumuz with regard to qualified teachers.10), general secondary. Additionally, there is also considerable variation by region in the percentage of qualified teachers (MoE, 2010). 2.5.3 Learning and school environment in primary schools (1-8) School facilities have impact on access, quality, efficiency and equity. The school facilities are tools to attract students in general and girls in particular. The type of school system (shiftoperated or non-shift) and availability of water, latrines, clinics, libraries, laboratories and pedagogical centers in schools in 2008-09 are presented in the table below(Ministry of Education, 2010). Table 11: Availability of facilities in primary schools Type Percentage Remark Shift System 28.4% Double shift Water 34.2% Tap & Well Latrines 90.5% Some boys & girls pit Clinics 11.6% - Libraries 35.7% - Pedagogical Centers 49.6% - MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) This is a very daunting figure at national level, worse among these many of the facilities such as the tap water, latrines, and libraries and clinics are ill-equipped, overused or not functional. 2.5.4 Instructional time 15 Worldwide, countries officially require an average of 700 annual hours of instruction in grades 1 and 2 and nearly 750 hours in grade 3. By grade 6 the average is 810 hours. Official requirements in sub-Sahran Africa are close to the global medians but the actual number of instructional hours children receive is often less than required. In the region, official school year starts late due to high teacher turnover and late teacher postings. Schools often start the school year a month late, end it a month early and have high student absenteeism, which results in as many as 200 to 300 fewer hours of instructional time than the official calendar requires. Significant loss of instructional time and inefficient use of classroom time are indications of poor education quality, with detrimental effects on learning outcomes (Regional Overview subSaharan Africa, UNESCO, 2008). The instructional time does not seem to be optimally used in Ethiopia because of various reasons including cultural and economic factors. 3. Challenges of Education for all in Ethiopia 3.1 Inefficiency of the system of education 3.1.1 Repetition rate This indicator measures the proportion of students who have remained in the same grade for more than one year. Current national policy requires that promotion be based on students’ continuous assessment results for the first three grades of primary school. Repeaters in these grades are still being reported since the policy it is not fully implemented in all schools. Table 14: Repetition rate by grade & gender in 2008/09 Grade/Gender 1 % 2% 3% 4% .5% 6% 7% 8% Male 6.4 5.7 5.7 6.7 8.3 6.4 9.1 10.5 Female 6.0 5.2 5.0 5.9 7.5 5.6 8.7 9.5 Total 6.3 5.5 5.4 6.3 8.1 6.3 9.0 10 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) As noted in the above Table, the lowest repetition rate was at grade 2 and the highest in grade 8. In grade 8, girls’ repetition rate was lower than that for boys. Repetition rates for grade 8 are 16 higher, in part, because of a national policy that those who do not pass the School Leaving Examination must repeat grade 8 prior to retaking the exam. Table 15: Repetition rate by gender Gender/Year Boys (%) Girls (%) Total (%) 2004/05 3.6 4.0 3.7 2005/06 3.8 3.7 3.8 2006/07 6.4 5.7 6.1 2007/08 6.6 5.7 6.1 2008/09 7.0 6.3 6.7 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) Even though repetition something that should be eliminated in both gender, it is encouraging to observe that the pattern of repetition rate of girls tend to be lower than that of boys. Further more; evidences suggest that the repetition rates are relatively similar across regions, with the exception of Tigray, Amhara, Somali, Addis Ababa, and Dire Dawa where the repetition rates are below the national average of 6.7%. Benishangul-Gumuz had the highest repetition rates and Somali had the lowest. Female repetition rate is highest in Benishangul-Gumuz and low in Somali—conceivably because of some underreporting. 3.1.2 Drop-Out Rate Drop-out rate is a measure, typically by grade, of those who leave formal schooling. In most cases it is calculated as the remainder after subtracting from enrollment, those who repeat and those who are promoted to the next grade. As many countries have discovered, often students do not completely drop-out, they may enter education several years later, or seek out alternative education or other less easily measured opportunities for education. e Table 16: Primary school dropout rates by grade and gender (Grade 1-8) Grade/Gender Drop out Rate in Percent 1 % 2 % 3% 4 % 5 % 6 % 7% 8 % 1-8% Male 24.1 16.8 12.3 12.6 16.8 9.6 8.6 10.3 15.9 Female 21.6 13.6 8.8 10.1 13.0 5.9 3.9 13.4 13.2 17 Total 22.9 15.3 10.6 11.4 15.0 7.9 6.5 11.6 14.6 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) The proportion of pupils who leave school varies from grade to grade. In most cases this figure is higher for grade one than for later grades. At national level, 22.9% of pupils enrolled in grade 1, in 2007/08 , have left school before reaching grade two in 2008/09).The figure above shows that dropout rate is highest at Grade 1 and lowest at Grade 7. As noted in the above Table, for all grades except 8, the rate of dropout is slightly higher for boys than for girls. 2 00 1 E.C. (2008/09 3.1.2 Primary completion rate (PCR) The Primary Completion Rate is, internationally, an established measure of the outcomes of an education system. It has been specified as one of the two major education indicators for the Millennium Development Goals (MDG). Table 17: Primary completion rate by year & gender Gender/year Grade 5 Grade 8 Male Female Average Male Female Average 2004/05 65.2 49.5 57.4 42.1 26.3 34.3 2005/06 69.2 56.0 62.7 50.1 32.9 41.7 2006/07 71.6 61.6 66.6 51.3 36.9 44.2 2007/08 71.7 67.0 69.4 49.4 39.9 44.7 2008/09 79.4 78.4 78.9 48.4 40.5 43.6 MoE, Annual Abstract (2008/09) The PCR is low and shows clear gender disparity in completion rate which requires immediate intervention. 3.2 Access to educational opportunities 18 Access to education opportunities continues to be an obstacle, especially for females and other “most vulnerable children” children with disabilities, children from low income families and students from pastoral areas (e.g., Somali and Afar). Inequities in access to quality education are widespread, as better resourced schools are generally located in urban areas and in the nonemerging regions, particularly in secondary schools. 3.3 Lack of sufficient number and uneven distribution of teachers Following the the National Teacher Education System Overhaul (TESO,2003), there has been a lot of expansion and reform teacher development reform in place both in primary and secondary teacher education programs. However, evidences suggest that there is still a shortage of teachers and uneven distribution of teachers across different regions. Unlike the primary teacher education program which follows the blended approached, that is pedagogical and subject area integrated, currently the secondary teacher education program is redesigned to follow the addon which is not popularly accepted by teacher educators. 3.4 Limited access and uneven distribution pattern of ECCE Early childhood care and education has been one of the most neglected areas in the country. In the year 2007, The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia has for the first time developed National Policy Framework on Early Childhood Care and Education in the country. The Policy Framework was jointly developed by the three sector ministries which include the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Women, Children and Youth Affairs. This is a very encouraging step taken by the Government, and it is envisaged to expand and make ECCE accessible to all children in the years to come. At present, the participation rate of children accessing ECCE is nationally negligible. However, there are noticeable innovative approaches undertaken by public primary schools, that is opening/ and hosting early childhood programs in their premises in cooperation with the community. 3.5 Inadequate attention and uneven pattern of growth of adult and nonformal basic education 19 As indicated in ESDP 111 (2005/2010), a strategy to address the issue of adult and non-formal basic education through organizing programs for out of school children, young people as well as adults through organizing alterative basic education, functional literacy and skills training has been developed respectively. However, the number of persons served in these programs is far behind from the target set for the sector. The massive and complex problems related to expanding adult literacy and attaining sustainable national development cannot be solved unless adequate resources are allocated by the Government and mobilized regional and international organizations. Apparently, rich nations and international bilateral and multilateral organizations have also failed to maintain their promises(Ministry of Education, 2008). Therefore, there is a need to make series of follow-up and put a lot of pressures so that they can keep their promises or come-up with new initiatives to realize the targets set.. 3.6 Education quality Evidences suggest that achievements in access have noo nt been accompanied by adequate improvements in quality. In some areas, quality has deteriorated at least partly as a result of rapid expansion. The 2007 National Learning Assessment (NLA) in grades 4 and 8 show that student achievement is below the required levels and has declined during the period of expansion. For example, the composite score for learning achievement in grade 4 shows a reduction from 48 percent in the 1999/2000 baseline learning assessment to 41 percent in the 2007 NLA. Similarly, the composite score for grade 8 shows a decline from 43 percent in 2000 to 40 percent in 2007. Key factors identified in the 2007 NLA relating to low student learning outcomes include school organization and management; teacher development programs; school facilities and supplies; availability of textbooks, curricular and instructional materials, and language of instruction. The Ethiopian National Learning Assessment showed that the mean score for all subjects of grade 4 and grade 8 students declined from 48.48% and 39.74% respectively in 2004 to 39.8% and 36.6% respectively in 2007 .The decline in quality and the decreasing trend of students’ performance might therefore be attributed to the above mentioned interrelated factors (Ethiopian National Learning Assessment (2008). 20 3.7 The gab b/w the rate of enrollment & financing of the education system The Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia has been committed to the provision of better and inclusive education for its citizens. This is demonstrated, in part, through the more than doubling of the commitment to education as a part of the total government budget. For instance, both the absolute increase of funds to education and its continous to increase as a percentage of total spending on the past five years has made the education budget to reach 24.0% in 2008/09. Table 18: Education budget & expenditures Year/Category 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 % Education 4,538.9 5,990.6 7,632.5 9,632.5 11,340.7 25 30,998.2 41,070.9 48,035.2 14.6 24.6% 22.8% 23.6 Expenditure (million Birr)* Total Government Expenditure 27,803.8 33,615.9 (million Birr) % of Education of total 16.7% 17.8% Government *Birr : Ethiopian local currency, currently its exchange rate is I USD is about 17 Birr According to f ESDP IV (2010/11-2014/2015) the overall cost is around 134 billion Birr. 74% of the cost goes to recurrent spending and 26% for capital spending. About 37% of the program costs are for primary level, 11.2% for secondary education, 8.8% for adult education and some 21.7% dedicated to higher education. The relatively limited spending on TVET (8.0%) is, to a large extent, due to the important share of students expected to enroll in non-government schools. Spending on administration, advisory and support services is estimated at 7.2%.The Table hereunder presents the indicative financing plan, with a financing gap for each of the five years of ESDP IV, which compares the overall cost with the government contribution. Table 19:Estimated financing gap for ESDP IV (2010/11-2014/2015) (in billion Birr) 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 21 2013/14 2014/15 Total a. Estimated 18,286 19,748 21,802 24,113 26,742 110,691 b. Projected costs 21,898 26,533 26,871 29,834 29,102 134,239 Gap (a-b) -3,613 -6,784 -5,068 -5,721 -2,361 -23,547 Education budget The financing gap is estimated on the basis of assumptions about economic growth and about shares of education in the budget (ESDP 1V, 2010/2011-2014/15). 4. The Way Forward The ESDP IV focus of education policies will shift towards priority programs which address these challenges. Accordingly, the main challenges which ESDP IV will address in the years to come are spelt out as follows: i. Improvement in student achievement through a consistent focus on the enhancement of the teaching/learning process and the transformation of the school into a motivational and child-friendly learning environment; ii. The creation of inclusive programs which can accommodate the needs of all children with special needs , such as , the unreached, the socially disadvantaged and those with disabilities. It is further underlined that a significant decrease in the drop-out rates in the early grades and that also requires the promotion of ECCE. iii. A renewal of adult education with a specific focus on functional adult literacy. iv. Capacity building for knowledge creation in the domain of science and technology, through expanding TVET and higher education without sacrificing quality. v. Improvement of the effectiveness of the educational management and administration at all levels, through capacity development and the creation of motivational and attractive working environments. Finally, within the framework of the ESDP III, the MOE has developed a draft General Education Quality Improvement Program (World Bank, 2008). The proposed Program focuses on six components (i) Teacher Development Program (TDP) including English Language 22 Quality Improvement Program (ELQIP); (ii) Curriculum, Textbooks and Assessment; (iii) Management and Administration Program (MAP) with an Education Management Information System (EMIS) sub-component; and (iv) School Improvement Program (SIP) with a School Grants sub-component ( World Bank,2008). The program has been in place in the last two years in the primary and secondary schools all over the country, and its envisaged to make a difference in the quality of the educational system. Reference Anis K. 2007. Ethiopia Non-formal education. Country profile prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2008 Education for All by 2015: will we make it? Checkole K, 2004. Paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2005, The Quality Imperative, UNESCO. International Working Group on Education 2003.Critical issues in Education for all: gender parity , emergencies, Tuusula-Helsinki, Finland, Paris UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning. Ministry of Education,1997. Education Sector Development Program I (ESDP I) 1997/982001/02, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ministry of Education 2005. Education Sector Development Program (ESDP III), 2005/2006 – 2010/2011, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 23 Ministry of Education 2010. Education Sector Development program IV (ESDP IV), 2010/11 – 2014/15, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Women’s ,Children & Youth Affairs,2010.National Policy Framework for Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, 2003.National Curriculum Pre-service for Teacher Education Programs, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, 2008. Ethiopian National Learning Assessment (ANFEAE) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, 2007. National Learning Assessment (NLA) in grades 4 and 8. Ministry of Education, 2008. National Report on the Development and State of the Art of Adult Learning and Education (ALE), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ministry of Education,2010.Education Statistics Annual Abstract,/2008-2009/. EMIS, Planning and Resource Mobilization Management Process, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. Ministry of Education, 2003. Teacher Education Overhaul Handbook (TESO), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Transitional Government of Ethiopia , 1994. Education and Training Policy, Transitional Government of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. UNESCO, 2011. Education for All Global Monitoring Report The hidden crisis: Armed conflict and education. Gender Overview. UNESCO, 2008. Regional Overview : Sub-Saharan Africa.. 24 World Bank,2008. Project Appraisal Document. In support of the First Phase of the General Education Quality Improvement Program (GEQIP). 25