A question of density

advertisement

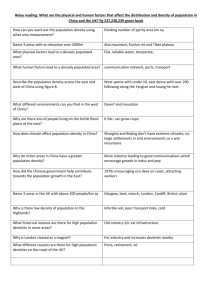

The question of density This subject follows on from the issues of ribbon development, sprawl and urban containment ( i.e. green belt) in that there is an argument that the pressures for new housing would have less damaging effects if housing was built at higher density, implying less use of greenfield or undeveloped land. The 2011 census indicates that the population has grown by about 7% in the last decade. Britain is one of the few European countries where this population trend is expected to continue and hence the importance of relating population growth to “population density". London's population is growing at 12% (twice as fast as 20 years ago) whilst in some of the northern region's population is shrinking with empty houses and vacant school places. In fact, the population in London and its growth is not evenly distributed. Tower Hamlets and Kensington and Chelsea show the highest population density, notwithstanding problems of gross and net density calculations, the latter taking into account parks and other unique features. It is expected that meeting population growth for the next 50 years will increase the developed area of England from 10% to 13%. (See variable and regional estimates in previous module) Going solo: one of the important factors in calculating the need for new housing is making an accurate estimate of household size now and in the future. Clearly the average size of household will affect the density of the population arising from the number of dwelling built on any area of land. The decline in average household size has leveled off, possibly due to the economic difficulties that young people have in forming new households. However, were there a sufficient supply of small dwellings it seems likely that household size would continue to decline. See Klinenberg E 2012 Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone Penguin. Klinenberg sees living alone as a remarkable social experiment as the first time in human history when large numbers of people of all ages are settling down as singletons. In some cases this is a force of circumstance, later marriages, divorce and bereavement rather than choice. In the UK 34% of households had only one person living in them, in the US it's 27%, with Sweden ‘leading’ the world at 47%. The tendency is more prevalent amongst women, and the young comprise the fastest-growing number of single person households. The rates of fastest-growing one-person households is in China, India and Brazil. This trend will have serious consequences for resources. But there are also questions about what this means for mental health and social fragmentation? What does it mean for the way we build our cities? The drivers are a combination of wealth and readily available social security (ie state provision as an alternative to family support) - those who can will. Pandering to privacy, has been one of the features of post WWII planning and architecture that may have contributed to a loss of a sense of community. Alternatively the pattern of residential development might be the response to social fragmentation with other causes. In either case there might be lessons to be found in Durkheim’s analysis about alienation and anomie. Durkheim, Emile 1951 Suicide : a study in sociology The Free Press. In terms of mental health housing providers could disclaim responsibility if people can feel just as alone when in a crowd or on the 15th floor of a tower block. Going solo was discussed in 31March 2012 through interviews with a number of people living alone. “Living alone should not be equated to loneliness. There's nothing more lonely than living with the wrong person.” Klinenberg says that this trend has produced significant social benefits. The revitalisation of cities and participation in public life? He claims that living alone can be more environmentally sustainable as singletons prefer apartments rather than big houses in inner cities rather than suburbs? Really? “I don't have to excuse myself, explain myself… (on children) I have insufficient self-esteem to need any duplication of myself in the world… Living alone means freedom… It's not about selfishness, just knowing what you like and doing what you want without having to take another person into account. Okay that sounds selfish but if you're going to be selfish and is probably best to do it on your own… And I know eventually change will come… So instead I have found ways of making aloneness feel less lonely. Downsizing from my family home, flat was a help… No more empty bedrooms.” Then there were the comments of those less happy with their singledom, “… things with most meaning to me always in my eye line… Cooking for one seems too much effort… I still think it's not natural… If it were left to me I'd make us all living longhouses… We need each other and especially the old… two is good when paying electricity bills… Cohabitation seems a greater leap in cities because it's all the harder to extract oneself if things turn sour. … It's what keeps otherwise functional adults living with their mothers… I own a cat… We are social animals… An extraordinary freedom. I just wonder how fragile [solos] are and what it might take for us to rediscover how much we need other people.” However, a remarkable change has occurred in the composition of households. The number of households with 3 or more generations living under the same roof was increased by 7% in the past 5 years reaching levels last seen in the Victorian times. Before leaving the subject of social interaction there is the recent phenomenon of social media and the communications revolution that allows people to enjoy an intense social life even when living alone. Journalist Francis Hope described another form of in-between state, “Heaven is the ideal state… when one is alone but expecting company.… A perpetual lunch date lunch date in an hours time. " He found more pleasure in the expectation of company than in the meeting itself. In fact, to have the meeting would cause the inconvenience of having to arrange another. Resources: Them seems to be little doubt that sharing space and facilities with others could lead to less use of a number of important resources; space, water, heat and materials required to build stuff. Normally, dwellings need only increase the bedrooms to accommodate additional household members, sharing kitchens, access/corridors and reception rooms. Notwithstanding a trend to increase the number of bathrooms, many older houses still have a “family" bathroom with possibly a small en-suite with the master bedroom. While water for washing and flushing might not be shared that for gardens and cooking normally is. The economy on space heating will depend on the controls of the system but the heating of all common parts would obviously be shared. Density in the round: In a recent study, Cooper R and Boyco C 2012The Little Book of Density Lancaster University] density was found to have many dimensions, including relationships between a number of important factors fundamental to existing and new built-up areas. At least indirectly, density is a factor impacting on our quality of life and mental and physical well-being. 23 different measures of density were identified although, in fact, only dwellings per unit area is in general use and has incumbency. The reason that ‘bed spaces’ is not used as a measure is normally due to uncertainty as to whether the beds are actually slept in (although there is no less uncertainty about how many people live in each dwelling). However, data in respect of dwellings per acre or hectare is most easily obtained. Cooper and Boyco looked at 75 studies which included density in their analysis and sought opinions from 129 built environment professionals. The general perception is that in areas of higher density there was better support for public transport and less car ownership and use. However there are more pedestrian casualties and people walk less for leisure purposes. Building at high densities is more energy-efficient. There is a negative impact on mental well-being at higher densities resulting in depression, withdrawal, strain, and poorer quality of family life. Less privacy means less friendliness. High densities contribute to increases in the occurrence of adolescent obesity, increased rates of heart disease and more drinking amongst adults. High densities create better social situations in terms of equality and mixed tenure (including affordable housing) than do lower densities. In terms of the design of residential areas, low densities were regarded as about 23 dwellings per hectare, medium densities at 44 dwellings per hectare, and high densities at 79 dwellings per hectare. 30 d/h or 12 p/a is the current norm outside central urban areas. The top 3 drivers identified for higher densities were the efficient use of land, increased profitability and more viable public transport. This aligns with the predominant belief that it is developers and local authority planners most involved in density decisions. Urban designers and architects are 4th and 5th likely to influence density decisions. Those surveyed thought that the LPA should be most influential and developers 7th. Cooper and Boyco concluded that there is a lack of thinking about the future (sustainability and resilience) when considering density, with an overconcentration on the present context. Having access to studies from around the world would serve to demonstrate what good density looks like and how it functions. Such comparables would be useful in making some more informed density decisions. In fact, Lord Richard Rogers has for many years used Barcelona as what he sees as a templat of well functioning urbanism. When it came to the important issue of sustainability, there were unanswered questions about what densities would prove to be sustainable and for whom? Official advice:The Government’s 1992 Planning Policy Guidance Note 3 on Housing suggested that there was no longer any need to pack houses together at 20 or 30 to the acre and the 2000 revision discussed achieving high quality housing and the assessment of design quality “… Well laid out so that all space is used efficiently, is safe, accessible and user-friendly… Is well integrated with and complements the neighbouring buildings and the local area more generally in terms of scale, density, layout and access.” (emphasis added). PPG3 2000 urged the Effective use of land: concentrating on use of previously developed land (brownfield) and efficient use of land, LPAs developing housing density policies should have regard to demand and need, infrastructure capacity, adaptation to the impact of climate change, accessibility (particularly public transport), characteristics of the area (including mix of uses) and the desirability of high-quality well-designed housing. “Reflecting the above, LPA's may wish to set out a range of densities across the plan area rather than one broad density range although 30 dwellings per hectare should be used as a national indicative minimum to guide policy development and decision-making until local density policies are in place." The density of existing development should not dictate that of new housing by stifling change or requiring replication of existing style or form. If done well in terms of the design and layout new development can lead to a more efficient use of land without compromising the quality of the local environment." As a boost to the supply of housing paragraph 47 of the National Planning Policy Framework 2012 suggests rather blandly that local planning authorities should “set out their own approach to housing density to reflect local circumstances". And paragraph 59 counsels against unnecessary prescription in respect of density. The conclusion could be drawn from official advice that density is recognised as a measure of the efficient use of land but not necessarily an indicator of the quality of either a house or residential area. Garden grabbing; mainly because the PPG3 had classified gardens as being ‘previously developed land’, more suitable for development than greenfield sites, there was a flurry of applications for developments effectively intensifying the density of residential areas. In turn, there was a backlash that caused a specific amendment to the National guidance that required greater care to be given assessing the impact of such developments. The rate of planning permissions granted for developments in gardens sharply decreased. The Garden controversy: this was a study conducted by Wye College (University of London) in 1956 into the productivity of gardens in low-density residential areas. A discussion of this topic is included as a separate module as an Annex to the Question of Density. Another more recent controversy is building around the construction of basements in areas of very high land values (eg Kensington) but which are making very substantial increases to the floor area of dwellings and the density of the areas. In most cases the underground accommodation is only suitable for cinemas, and parking rather than more bedrooms that would increase the population density. Design and density was published in 2002 by the CPRE as part of its “sprawl patrol" campaign and in response to PPG3 2000 designed to “radically alter the way in which we build new homes in this country… And put an end to the wasteful, badly located and poorly designed house building that has gone on for the last 20 years. " There were signs of densities falling towards 20 dwellings per hectare that were unnecessarily wasteful and densities of 30 to 50 dwellings per hectare were recommended. The CPRE claiming that “density matters", listing the advantages of the higher densities as: complementing the character of an area, opportunities for social contact, sustaining public transport, encouraging feelings or of safety and security, absorbing parked cars without intrusion, this creating a sense of identity and improving property values. Wanting to allay misplaced fears, the nub of the issue was said to be in the design of new buildings and not density. One of the unfortunate features of older towns and villages is the scale and appearance of on-street parking that is exacerbated at higher densities. CPRE fear that density was being controlled by the availability of parking spaces rather than the quality design. The Briefing then demonstrates the imprecision of counting dwellings. One large dwelling could vary from accommodating 8 people and 4 cars to just 2 people and 2 cars (the empty nest). The same site could accommodate either flats or houses with similar built forms but accommodating a significantly different number of households and therefore, people and cars. The level of occupancy appears to be the most important determinant. In fact, in suburbs and villages under occupancy is the prevailing factor with over 70% of dwellings having one or more spare bedrooms. Nothing gained by overcrowding was published by the Town and Country Planning Association in 2012 that explained how the Garden City type of development may benefit both owner and occupier. This was, a reproduction of a 1912 publication of that name by Raymond Unwin a century earlier. Unwin explained how the traditional by-law housing layout prevalent between 1870 and 1910 was inherently inefficient in its use of space because of its excessive street length. By turning the traditional layout inside out, whereby houses faced outward onto streets but inward onto a huge communal gardens, effectively street space was turned into garden space. This was the principle that had been applied by Unwin at Brentham but could not be claimed as a new invention as it had been the basis for the Norlands Estate in Notting Hill (1850s) and in Maida Vale West Hampstead between 1870 and 1900. More efficient use of land was equated to a lower rent or at least much more land and buildings for the money. The average density was 30 dwellings per hectare, representing a more harmonious combination of city and country, dwelling house and garden. Ideas from this report were incorporated into the 1919 Tudor Walters Committee Report that enshrined 12 houses per acre (30 d/h) that had been applied at Letchworth. The concept of the superblock minimized the amount of road required to be paid for by each unit. Roads represent a major expense and junctions are a loss of developable frontage. This layout is also more efficient to patrol by police or scavenger cart (sic). The low-density would mean a larger land take and possibly more roads and drains but Unwin was much more interested in the quality of the residential environment than in the loss of agricultural land. However, Unwin also calculated that the actual size of the town (the distance from edge to centre) would not increase dramatically giving a guide that an 11 miles radius could accommodate 8 million people and 14 miles accommodated 12 million in London; about 25% increase in radius accommodating a 50% increase in population. Unwin sought to demonstrate that the increased rental value was disproportionately less than the increase in units. It is still the case that 2 smaller units do not necessarily provide a greater return than one large one.. In 1912, Unwins said that, “Experience has shown that where plots have been laid out by landowner it is very difficult to induce the speculative builder to a erect upon them small cottages, even where the demand for small cottages is very great. It is of great importance when limiting the number of houses to the acre that the reduction of the number of houses should also have a limit on the size of the house." One hundred years later the mechanism still does not exist to provide and maintain small houses of large areas of land. In summary, the term density is often used when describing housing areas but there does not appear to be any clear relationship between the number of dwellings built on an area of land and the quality of the design or of life of the residents. Due to very variable occupancy rates, the buildings do not always have a clear relationship with population density. It does seem that with small and still declining household size, that a large number of smaller dwellings would be required to create a better balance, and possibly reduce the level od under-occupation. Unless such dwellings are built on generous plots then smaller dwellings implies higher overall densities. Finally, there is a useful concept of Lifetime Neighbourhoods which implies an area where people can move to meet their changing household needs rather than a Lifetime Home where such needs can be met without moving. The former would result in lower levels of under-occupancy (ie efficient use of buildings whether or not they represent an efficient use of land). This would seem to be increasingly importance in our search for sustainable development. Such neighbourhoods are likely to require a range of house types built at different densities.