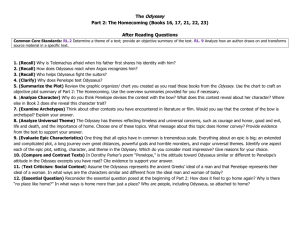

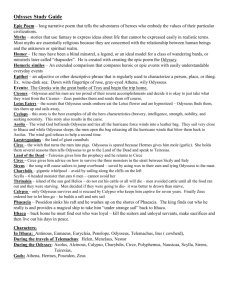

unit plan - Achievement First

advertisement