Preface - Beef eating in ancient India

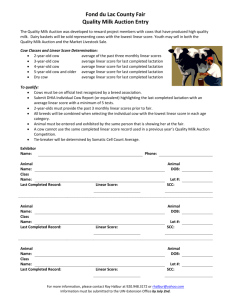

advertisement