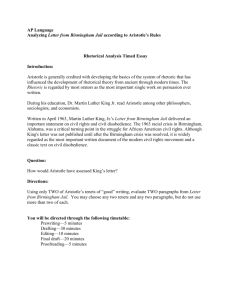

View/Open - CSUN ScholarWorks - California State University

advertisement