Teaching Forensic Psychology

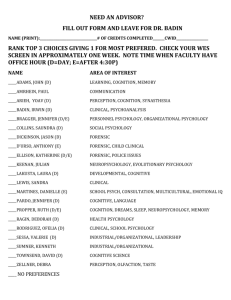

advertisement

Teaching Forensic Psychology: Psychology in the Courtroom by Brenda Russell Castleton State College Castleton, Vermont Misconceptions Spread by Court TV As I write this, Court TV and television news report the latest on the trial of 15-year-old Christopher Pittman, accused of killing his grandparents when he was 12. If convicted, he faces up to 30 or more years in prison. He offers the use of antidepressants, Zoloft and Paxil, as his defense. A finding of guilty but mentally ill or insane will result in hospitalization for an undetermined period of time. This murder case is the first of its kind to argue the safety and use of antidepressants in children. For many students, the term forensic psychology brings to mind glamorized depictions of specialists solving crimes using elaborate crime labs complete with unlimited resources, not the experts involved in the Pittman debate. Often these perceptions are not correct. With the advent of Court TV, and television portraying forensic sciences and forensic psychology as one entity (e.g., CSI, Profiler, Forensic Files), it is no wonder why students may have the wrong impression of what constitutes forensic psychology. One major misconception is that the role of the forensic psychologist is that of a "profiler." I find this even among the applicants to our forensic psychology graduate program. It is likely that many high school teachers of psychology have experienced students who come to them for advice because they would like to be a profiler. Profiling is only one of many possible roles for forensic psychologists. For teachers of introductory psychology and AP courses, my aim is to clarify some of the misconceptions associated with the term forensic psychology. Defining the Field Forensic psychology is generally associated with one of two perspectives: clinical or research. It should be noted that these perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Many clinicians conduct research, and many researchers also provide clinical assessment or treatment in legal contexts. Forensic psychologists typically obtain their master's or doctoral degrees within various subfields in psychology. Clinicians often obtain licensure before working with the courts. Within these two perspectives, there are four general roles for forensic psychologists. First, thebasic forensic psychologist might conduct research on legal issues and publish their research. Second, applied forensic psychologists may be clinicians working directly with the court and clients, and/or using the latest research to impart information as an expert. Third, a forensic psychologist may be a policy evaluator, evaluating whether laws regarding speed limits lower rates of fatal accidents or whether seat belt laws are effective. Last, the forensic psychologist may be an advocate -- paid to work for the prosecution or defense (e.g., jury consultant). The first perspective suggests forensic psychology be broadly defined. In this respect, the application of psychological methods, theories, and concepts to the legal system can be considered forensic psychology. In other words, research associated with topics such as delinquency, victimology, jury decision making, eyewitness testimony, or attitudes toward the death penalty can be considered forensic psychology. Also falling within this realm is applied research with regard to evaluation of public policy or treatment at state or federal agencies such as correctional facilities. Expert Testimony In this regard, researchers may be called in as experts to testify about their own research findings that relate to a specific case or to speak in terms of their research findings in a more general framework (providing social framework from which legal actors can make more informed decisions). Such information may come in the form of expert testimony or case or legislative briefs (Monahan and Walker, 2002). For example, if a psychologist conducted research on the effects of antidepressants and psychotic behavior leading to murder or the safety of antidepressant use in children, that psychologist may be called to testify for the defense in the Pittman case. In contrast, clinicians work directly with clients and the courts. Clinicians may conduct research to develop assessment tools (e.g., predicting the future dangerousness of an offender), provide treatment or intervention, or examine prevalence and incidence of forensic disorders. As practitioners, they may provide treatment or assessment in correctional settings or police departments, or they may be called to testify in a case with regard to insanity or competency. Forensic assessment can be done during or before trials, assisting the prosecution or defense in describing the defendant's state of mind or culpability. Clinicians may be called upon by the courts to aid in decisions of child custody or civil commitment, or to give opinions associated with effects of a particular mental illness to help shed light on a defendants' behavior. They may also explain such things as the extent to which the defendant or plaintiff exhibited symptoms, repressed memories, dangerousness, or rehabilitation. The Pittman case exemplifies where many of these facets of forensic psychology collide, often with conflicting conclusions. A forensic psychiatrist (trained as an MD) in the Pittman case testified for the defense, stating she believed Pittman committed the murders while in a psychotic state induced by Zoloft. However, prosecutors have their own team of experts and clinicians testifying Christopher knew what he was doing when he killed his grandparents. Clinicians for the defense team attempted to demonstrate Pittman was not legally responsible for his actions and to show he was insane or mentally ill at the time of the crime, based on his use of antidepressants. Profiling and Behavioral Science Although this discussion is designed to help educators guide high school students regarding the realities of forensic psychology, many students will still profess an interest in becoming a profiler. Profilers obtain information from all aspects associated with the crime in order to create a biographical sketch that provides demographic, personality, and behavioral characteristics to help law enforcement direct their investigations. The FBI's Behavioral Science Unit (BSU) has a team of a few dozen profilers. However, students must realize that most have been FBI agents in the field for many years before they are considered for BSU. The FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia, offers classes in profiling, as do many forensic psychology graduate programs. To date, there is no accredited or accepted curriculum to become a profiler in either law enforcement or the psychological community. Regardless of the route chosen to become a profiler, job prospects for the future profiler remain fairly poor. And despite the proliferation of profilers in media and television, there is little empirical research to support the effectiveness of profiling. Conclusion As I complete this paper, I realize that I have hardly scratched the surface of the many roles of the forensic psychologist. It is important to note when directing high school students that while the bachelor's degree provides the basis in the field, the minimum educational requirement for psychologists is a graduate degree. While some programs offer concentrations in forensic psychology, specializations typically begin during graduate studies. Specialties in forensics psychology may be subsumed under subfields such as neuropsychology or clinical, social, or legal psychology. Many career opportunities exist in forensic psychology. Undergraduate and graduate programs are stepping up to provide training for the future forensic psychologist. Twenty-five years ago, most people would not know what a forensic psychologist was, and 25 years later, we still struggle with an accepted definition. Limiting forensic psychology to criminal or civil courts or to research or clinical-based fields seems constricting and neglects the contributions of each study of the legal system. But whether we broaden the definition, accepting the term with its many varied aspects or not, experts under the umbrella of "forensic psychology" will continue to help us understand complexities such as those found in the Pittman case. Reference Monahan, John, and Laurens Walker. Social Science in Law: Cases and Materials. 5th ed. New York: Foundation Press, 2002. Brenda Russell is associate professor and coordinator of the forensic graduate program at Castleton State College in Vermont. Her research interests include social psychological aspects of jury decision making, program evaluation, gender differences in sexual harassment and assault, female aggression and male victimization.