EIS for the imperial sand dunes recreation area

advertisement

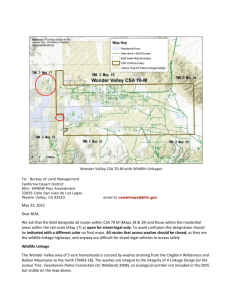

PLACE PHOTO HERE, OTHERWISE DELETE BOX EIS FOR THE IMPERIAL SAND DUNES RECREATION AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN A CASE STUDY FOR PROFESSOR STEPHAN SCHMIDT, CRP 5540 – CORNELL UNIVERSITY December 1, 2010 Andrew Bruce Andrew Bruce Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area Management Plan and Proposed Amendment to the California Desert Conservation Plan 1980 Organization Lead Agency: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District El Centro Field Office Involved Agencies: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service California State Historic Preservation Office Native American Tribal Governments Summary The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) produced this Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to investigate the potential environmental impacts from the revision and updating of the Recreation Area Management Plan (RAMP) for the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area (ISDRA). The ISDRA is the largest mass of sand dunes in California and is a world-renowned location for offhighway vehicle (OHV) recreation. The ISDRA receives over 3 million OHV visitor-use days per year and is one of the most popular OHV areas west of the Mississippi. The ISDRA is also home to several endemic and fragile plant and animal species. “To fulfill its obligations under the Federal Land Policy Management Act (FLPMA) and under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the BLM manages recreational use after considering the effects of the recreational activities on the conditions of special-status species, and other unique natural and cultural resources” (BLM, 9). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) is the primary consulting agency for the EIS, because they control federal agency activities with respect to the ESA. Increasing OHV use in the ISDRA has brought about “minor occurrences of occasional trespasses in the North Algodones Dunes Wilderness and on private lands” by OHV users (BLM, 10). This increasing level of use and number of violations has created some user conflicts and motivated the revision of the RAMP. Finding an appropriate balance between these two values, recreation and bio-diversity protection, is another primary concern of the RAMP and the EIS. While the EIS covers a number of environmental impacts, this case study focuses on impacts to bio-diversity and habitat. Chronology 1976 - The Federal Land Policy Management Act requires the BLM to create management plans for all units managed by the Bureau. 1979 – The first RAMP for the ISDRA is completed. 1980 – The California Desert Conservation Area Plan, which guides all BLM plans in the area including the ISDRA RAMP, is completed. 1987 – The second RAMP for the ISDRA is completed. 1994 – The California Desert Conservation Act designates a portion of the ISDRA, the North Algodones Dunes, as wilderness. 1998 – The BLM issues a Notice of Intent for the new ISDRA RAMP and begins public planning meetings. 2000 – The BLM conducts initial Public Scoping Meetings. 2000 – The Center for Biological Diversity filed for injunctive relief in U.S. District Court against the BLM claiming the BLM violated the ESA because they did not consult the USFWS. Camping and OHV closures occurred in five areas of the ISDRA during the interim. 2001 – The BLM conducts subsequent Public Scoping Meetings. 2002 – The BLM provides the Draft EIS and RAMP for public comment. 2003 – The Final EIS and RAMP are produced. Andrew Bruce Andrew Bruce Project Description The revised RAMP informs management decisions about the land use and resources of the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area (ISDRA) and seeks to find a balance between recreational and ecological values, while promoting the health and safety of visitors, employees, and nearby residents. Under the new RAMP, the ISDRA is divided into eight management areas: 1) Mammoth Wash Management Area, 2) North Algodones Dunes Wilderness Management Area, 3) Gecko Management Area, 4) Glamis Management Area, 5) Adaptive Management Area, 6) Ogilby Management Area, 7) Dune Buggy Flats Management Area and 8) Buttercup Management Area (BLM, 2). Each management area provides different recreational opportunities based on the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) classification system. The ROS system dictates the visitor supply and types of allowed activities based on users needs and management area capacity and ecological sensitivity. Alternatives The EIS considers four alternatives: 1) No Action Alternative, 2) Recreation and Resource Protection Alternative, 3) Natural and Cultural Resource Alternative and 4) Motorized Recreation Opportunities Alternative. The names are accurate descriptions of the general approach of each alternative, although alternative 2 does emphasize recreation more than natural resources. Alternative 2 was preferred in the EIS and was ultimately implemented. The primary difference between the alternatives is the number of recreational users allowed each day, the type of OHV use allowed and the ROS classifications employed. All but the no action alternative, provide for a dust control plan, new ranger stations, new law enforcement tools, the implementation of fee-based programs and the provision of free use days. The no action alternative does not place a limit on visitor supply, while alternatives 2, 3, and 4 allow 80,000, 20,000 and 274,000 visitors per day respectfully. The no action alternative allows for unlimited OHV use in all areas except the wilderness zone. Alternatives 2 and 4 would allow for unlimited OHV use in six areas with permit use in one area and none in the wilderness. Alternative 3 would allow unlimited use in five areas and close three areas to OHVs, including the wilderness. Using the ROS, Alternative 2 would include one semi-primitive non-motorized area, two semiprimitive motorized areas, three roaded natural areas and two rural areas. Alternative 3 would include three semi-primitive non-motorized areas, three semi-primitive motorized areas and two roaded natural areas. Alternative 4 would include one semi-primitive non-motorized area, two roaded natural areas, three rural areas and two urban areas. Andrew Bruce Impacts Habitat Three primary habitat types exist in the ISDRA: 1) Creosote Bush Scrub, 2) Psammophytic Scrub and 3) Microphyll Woodland. Creosote bush scrub is the most common habitat type in the Colorado Desert. It is found on well-drained secondary soils of slopes, fans, and valleys. In the ISDRA, creosote bush scrub is found around the edge of the major dune area. This habitat type consists of relatively barren ground interspersed with widely spaced shrubs. Psammophytic scrub is found in the interior of the dune system between active dunes in small valleys called “bowls.” The soil in this habitat type is made up of fine sand. As the dunes shift, so do the bowls. Psammophytic vegetation is adapted to high sand mobility and deep-water percolation and most species are able to grow rapidly with favorable soil moisture conditions. Microphyll woodland is found east of the dune system in a large alluvial fan that drains the Chocolate and Cargo Muchacho mountains. The alluvial fan is crossed by many ephemeral washes. Microphyll woodland is made up of dense stands of trees and occurs in the larger drainages around dry channels and the sinks where they end. Vegetation in this habitat type is sparse in the open areas between the sinks. Loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitat are expected in all habitat types open to OHVs. The EIS does not elaborate further on how much loss, other than weakly stating a relative amount (more than alt. 1; less than alt.3), and does not indicate the form of degradation or what degree of fragmentation is expected. Impacts to habitat are expected from new facilities development, but the BLM determined that construction would occur in areas that already have heavy OHV use, so the impacts were expected to be minimal. Indirect impacts, such as soil erosion and dust generation, from increasing visitor use are also expected from facilities expansion. No impacts are expected in the areas closed to OHVs. For this reason, the number of acres open to OHV use, allowed by permit only and closed to OHV use are important indicators of the amount of expected impacts. While alternative 2 and 4 have the same number of acres in these categories, there would be more facilities built, more expected use and hence more expected impacts with alternative 4. The following tables provide these indicators for each alternative. Alt. 1 Habitat C. B Scrub P. Scrub Woodland Alt. 2 & 4 Closed aand Open 3,144 48,687 15,983 91,702 7,075 57,831 Alt. 3 Habitat C. B Scrub P. Scrub Woodland Habitat C. B. Scrub P. Scrub Woodland Closed Closed 3,144 15,983 7,075 Permit 30,019 24,726 37,749 Open 34,678 17,153 47,705 59,980 47,927 16,979 Special-Status Plants Potential impacts to special-status plants as a result of OHV use are expected to occur under each alternative. Special-status plants that are expected to be impacted are: Peirson’s milk-vetch, Algodones dunes sunflower, Wiggins’ croton, giant Spanish needle, and sand food. Each of these species is dependent on psammophytic scrub habitat. Under Alternative 1, about 85 percent of this habitat would be open to OHV use. Under alternatives 2 and 4, 63 percent would be open to OHV use, but the impacts are expected to be lower in alternative 2 because some of the open area would be adaptively managed. Alternative 3 would protect the more of this habitat, allowing only access to only 56 percent of the area; however, degradation within the areas OHVs are allowed is expected to be greater because of more intensive use. Open 18,668 66,976 20,082 Special-Status and Endemic Wildlife As with habitat types and special-status plants, potential impacts to special-status and endemic wildlife are expected under each Alternative. “Primary impacts to special-status and endemic wildlife include direct mortality from recreational vehicles. Secondary impacts include destruction of forage and habitat; crushing of burrows; attraction of predators due to improper disposal of food and litter; harassment and illegal collection of wildlife; harassment by unleashed pets; dust, noise, lights associated with OHV and camping activities; and increased potential for invasion of non-native plants” (BLM, 252) OHV use is generally concentrated within the psammophytic scrub and some special-status wildlife species like the Colorado Desert fringe-toed lizard, the flat-tailed horned lizard and endemic dune beetles would be killed or injured by OHVs. Also, OHV routes through microphyll woodland habitat and open desert wash areas are expected to impact the desert tortoise by running them over or crushing their burrows. OHVs may also affect Couch's spadefoot toad habitat by disrupting small ephemeral pools on which this species depends. Couch's spadefoot toad often group up during breeding season, placing them in greater risk if there is high OHV use. Measurement and Reporting of Impacts Interestingly, no measurements other than OHV use in habitats are provided for the impacts on biodiversity. No population numbers, expected deaths, quantifiable indicators of disturbance or expected injuries are discussed. Perhaps this data was unavailable, but it seems as though this would be necessary information for assessing impacts to special-status species. It is noted throughout the document, however, that specialstatus species “were considered in detail” and that the USFWS was consulted about these species (BLM, 255). Mitigation Mitigation for impacts to biodiversity is not expressly discussed in this EIS. In fact, this is the only sentence under the mitigation measures section for biological resources: “No additional mitigation measures are required beyond those management actions incorporated into the action alternatives” (BLM, 259). Within the action alternatives, reductions in impacts from the baseline are often touted as positive qualities of the various options. The document repeatedly emphasizes the expected effectiveness of the adaptive management area, making statements such as “impacts to special-status and endemic wildlife within the Adaptive Management Area and limited use area surrounding ISDRA are expected to substantially decrease” (BLM, 255). Restricting and prohibiting OHV use is also discussed as a method to reduce impacts, but no mitigation measures for OHV impacts on biodiversity in open areas are discussed. I would expect mitigation measures could include special-status species awareness and education campaigns for OHV users or improved signage in critical habitat areas, but no options were covered in the EIS at all. Also, increased law enforcement and the construction of law enforcement facilities in the ISDRA are proposed in the EIS, but this is completely disconnected from biodiversity protection despite the recognition that many of the expected impacts are related to unlawful activities. References United States. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, El Centro Field Office. Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area Management Plan and Proposed Amendment to the California Desert Conservation Plan 1980. Washington: GPO, 2003. CRP 5540 – CORNELL UNIVERSITY Andrew Bruce MRP, 2010 341 Ferguson Rd Apt 2A Freeville, NY 13068 Anb55@cornell.edu P: 303-859-2370 M: 555-555-5555 F: 555-555-5555