DeAndré A. Espree-Conaway 6700 Queenston Blvd. #432 Houston

advertisement

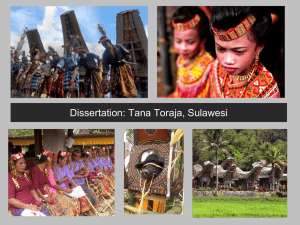

1 DeAndré A. Espree-Conaway 6700 Queenston Blvd. #432 Houston, Texas 77084 United States of America University of the South Student +1 (713) 876-7015 espreda0@sewanee.edu 2 This is a declaration that this manuscript has not been published or submitted for publication elsewhere. Thank you. Sincerely, DeAndré A. Espree-Conaway 3 THE AFFECTIVE SOCIALIZATION OF POWER: LANGUAGE, EMOTION, AND TRUST IN INDONESIAN SOCIO-POLITICAL KINSHIP Abstract Indonesians, during the Sukarno-Suharto era, referred to these first two Presidents as bapak or pak (father) and the Presidents referred to the Indonesian citizens as adik (children). Considering the tumultuous times and occurrences under both Presidents, the questions emerge: What do Indonesians do when that fatherfigure is not so fatherly? And how do Indonesians trust such a ‘patronizing paternal’ figure? In this investigation, I explore how affect as expressed though language, specifically kinship terms, works as a vehicle of social power by leaders under New Order politics in Indonesia. I explain how Indonesian citizens in this époque dealt with both leaders by means of the tie that affectively-charged language has with the self. Keywords: Affect, Politics, New Order, Indonesia, Language. Introduction The concepts and family terms wielded (mother, father, aunt, uncle, grandparent, etc.) ideally allow Indonesians to recreate the familiarity, caring, and protectiveness of families beyond the household into the public sphere --- Lorraine V. Aragon 4 In the quotation above, Aragon acknowledges the pervasive use of kinship terms in Indonesia, even outside of the realm of consanguineous family. This is not the most usual occurrence considering that even in the West people do this, although most often in a cheaply metaphorical sort of way. However in the context of Southeast, where strong ties to a “broader” sense of “family” that relates more to place than persons at times leads to an interesting investigation. This investigation focuses on the area where people use kinship and relational terms in the realm of national politics. Indonesians, during the New Order period and slightly before, referred to their first two Presidents, Sukarno and Suharto, as bapak or pak (father) and the Presidents referred to the Indonesian citizenry as adik (children). Aragon notes that “these linguistic practices at times instill a cozy family solidary to Indonesian politics, but they also sometimes aid the surrender of political authority to some lessdeserving father figures, who reciprocate with patronizing paternalism”(Aragon 2011; Shiraishi 1997). The implications of kinship terms used this way in politics raises the question, what do Indonesians do when that father-figure is not so fatherly? If the person in authority is not properly fulfilling his duties, people revolt; however not to overthrow the system, but to return the system to a state of order with someone else who does fulfill their duties, so that balance in society persists. In other words, if the father does not do as he should, find another father. Before I proceed, I must introduce the political ‘fathers’ Sukarno and Suharto. Sukarno (b.1901 - d.1970), Indonesian’s first President who was in power for twenty years, was the son of a Javanese man of lower aristocracy and a Balinese woman. He was educated at Surabaya, meeting nationalist leaders and then at Bandung, studying engineering. He founded the Indonesian Nationalist Association (which later became the Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI), Indonesian Nationalist Party) in 1927. The Dutch colonial authorities against which he fought 5 detained him in 1929 for his nationalist undertakings until 1931. They then rearrested Sukarno in 1933 throwing him into exile at Flores and then at Bengkulu in 1938. Freed 1942 by the Japanese, he led many governmental activities including heading one group in order to prepare for Independence and participating in drafting of the first Constitution. At the end of the war, Sukarno’s men kidnapped him in a forced attempt to declare independence, which occurred August 17, 1945. Sukarno became Indonesia’s first president until 1965 (Vickers 2005: 225). After seven attempts on his life, he organized a “Guided Democracy” policy for governing Indonesia. In his autobiography, Sukarno recounts some of his policies concerning freedom of speech: A foreign journalist asked, “But didn’t you criticize the government when you were a young rebel?” “Yes,” I conceded. “I wrote blistering editorials against them. But they were the Dutch. That was not OUR government. However, I am now THEIR government.” “When the last remnant of the Revolution is some day over, will you then permit freedom of the press?” he asked me. “I’ll tolerate it only within certain limits. I think now that I shall never permit that free freedom which gives the public prints the liberty to murder their Heads of State for the rest of the world to see. Japan, for instance, has headlined false and vicious things about the Crown Princess Michiko which were so harmful they destroyed her self-confidence and faith in herself and she became ill. In a new baby country like ours it could destroy us. I give my newspapers freedom to 6 write whatever they like provided it’s not destructive to the safety of the State.” “And if they go too far?” “I twist their ears. This means, I forbid the guilty papers to print for one week, sometimes two. Should it occur again, I suspend them for three weeks. The next time I shut their doors indefinitely (Sukarno 1965:280). These Guided Democracy policies led to the coup of 1965 and the rise of Suharto to power (cf. Vickers 2005: 225). The New Order era had begun. The new President Suharto (b.1921) originally from Central Java, initially obtained his military training from the Dutch and then later the Japanese. He quickly rose to the position of officer during the Revolution. As one of the few military leaders not pursued during the coup, he seized control of Indonesia and served as President until 1998 leaving by forced resignation (Vickers 2005: 228). The following report describes some of the horrific occurrences during Suharto’s term. The report documents killings in East Java between December 1965 to January 1966. The author is unknown. The British organization Tapol2 obtained the report in the 1970s. It was probably obtained from Indonesian exiles in Europe. Tapol’s Bulletin published these sections of the report (Cribb 2009: 347): Singosari, Malang regency A young boy, member of the IPI (Union of Students of Indonesia) and son of Pak Tjokrodihardjo, who was a member of the local PKI [Indonesian Communist 7 Party]3 committee in Singosari sub district, was arrested by Ansor. He was then tied to a jeep and dragged behind it until he was dead. Both his parent committed suicide. Urip Kalsum, a woman was a lurah [village head] of Dengkol in Singosari, was a member of the PKI. Before being killed, she was ordered to take all her clothes off. Her body and her honor were subjected to fire. She was then tied up, taken to the village of Sentong in Lawang, where a noose was put around her neck and she was hacked to death (Cribb 2009: 348). Pare, Kediri regency Suranto, headmaster of the High School in Pare and one of the leaders of the Pare branch of Partindo [Indonesian National Party] and a member of the DPRD [the Regional House of Representatives ] Kediri district, lived in the village of Pulorejo, Pare.4 On October 8, 1965, at about 5:00 p.m. he went by bicycle to meet his wife, nine months pregnant, who had been at an arisan (rotating credit and social club). On the way home, they were stopped and taken prisoner by an Ansor gang. They were beaten until they fell unconscious and were then killed. The man’s head was cut off and his wife’s stomach was cut open, the baby taken out and cut to pieces. The two bodies were thrown down a ravine to the east of the market in Pare. For a week afterwards, their five children who were all small (the oldest was eleven) had no one to help them because the neighbors were warned by Ansor members that anyone helping them would be at risk (Cribb 2009: 348-9). After briefly examining the deeds of Sukarno and Suharto, again it raises the question, what do Indonesians do, especially in speech, when that father-figure is not so fatherly? In beginning to 8 approach this question, one must realize that kinship terms are filled with affect (cf. Besnier 1990: 422). Affect is the substance into which society affixes itself in a person. This implies that national politics, the agent of societal power, is able to ground itself deep in the emotions of each individual person which is, as is the general rule Indonesia and most of Southeast Asia, more socialized. Affect, being the ‘heart’ of the self, is the substance upon which trust and, in the Indonesian case, social trust predicates itself. In addition, affect embeds itself cognitively in the individual as Bell and Wolfe writes that psychological research is beginning to realize. Bell and Wolfe state, “Emotion regulation research usually focuses on socio-emotional development; however, we have proposed that the neural mechanisms underlying regulatory processes may be the same as those underlying higher order cognitive processes” (2004: 369). Affect, connected with the visceral (neural and physiological) and cognitive subject, is the basis of intersubjective5 trust. But how do Indonesians trust such a ‘patronizing paternal’ figure? This question is what drives this study. Here in my paper, I explore how affect as expressed though language, specifically kinship terms, works as a vehicle of social power by leaders under New Order politics in Indonesia. I explain how Indonesian citizens in this époque dealt with both leaders by means of the tie that affectively-charged language and behavior have with the self. Before I begin to explain the response I found to this question of kinship, I will outline what is known about the interface between language and affect along with its position in culture and society with a view towards its use in social power and specifically politics in SuhartoSukarno era Indonesia. Following Besnier (cf. 1990: 421), I have chosen to take on a broad and flexible definition of “affect” as ‘an open, but empty’ term waiting to be defined by specific empirical 9 cases—in this instance the Javanese and Toraja cases. I also use affect and emotion interchangeably. Anthropologists maintain that affect and affective profiles are primarily social and, moreover, may also distinguish human cultures and societies from one another (cf. Panoff 1995: 210). Heelas notes that “different cultures and societies hold different kinds of emotions. There are very considerable differences in the number of emotions clearly identified; what emotions mean; how they are classified and evaluated; how the nature of emotions is considered with regard to locus, aetiology and dynamics; the kind of environmental occurrences which are held to generate particular emotions; the powers ascribed to emotions; and management techniques” (2007: 31). Psychologists, on the other hand, place emphasis on the self or the subject6 as the root of affective experience. Byron Good observes that this “individual/social binarism” has plotted itself “onto a [major] disciplinary divide between psychology and anthropology” (Boellstorff and Lindquist 2004: 438). Following Good (2004: 532) and Boellstorff and Lindquist (2004: 438), I endeavor to analyze affect as both a sociocultural and a socioculturally specific phenomenon with reference to and engagement with the individual without ontologizing either self or society. The social stance is important as way to reveal “deeply held assumptions (and not just Western ones) about the relationship between embodied versus transpersonal modes of being” (Boellstorff and Lindquist 2004: 438). However, the subject or the individual is just as important seeing, as Good explains, that “[t]he subject is at once a product and agent of history; the site of experience, memory, story-telling and aesthetic judgment, and of conscious and unconscious motives, feelings, and forms of symbolization; an agent of knowing and knowledge as well as of action; and the conflicted site for moral acts and gestures amid impossibly immoral societies and institutions” (2004: 531). In addition all the major theories in ‘emotion or affective science’—which while being somewhat interdisciplinary 10 (anthropology, psychology, genetics, etc.) still leans heavily on cognitive and neurosciences—do not deny the connection between the social world and the individual body—a connection that I hope to make. Linking the binarism is essential to a more wholistic understanding of humans (the goal of Anthropology), but moreover, much more specifically, a wholistic understanding of the Indonesian case of language and affect. Language and affect studies approach a new frontier in cultural and linguistic inquiry. While Anthropologists have made substantial ground in emotion and sociocultural studies—the legacy in American anthropology reaching back at least to the 1930s (Besnier 2011: 433)— exploring the interface between language and affect from the anthropological perspective is a much newer occurrence. Interestingly, most of these studies concern Southeast Asian and Oceanic cultures. Linguists have hardly even begun to explore this area of linguistic meaning. As Besnier states, “[A]ffect has been consistently set aside as an essentially unexplorable aspect of linguistic behavior, a residual category to which aspects of language that cannot be handled conveniently with extant linguistic models were relegated to be forgotten (1990: 420). In Semantics—a subfield of linguistics—Lyons delineates linguistic meaning into three constituents: referential meaning, “mapping of linguistic signs onto the entities and processes they describe”, social meaning, “consisting of the social categories…represented in language”, and expressive (or affective) meaning, “representing the speaker's or writer's feelings, moods, dispositions, and attitudes toward the propositional content of the message and the communicative context” (Besnier 1990: 419). Although Lyons draws a distinction between social and expressive meaning, I offer the two more often engage each other. Besnier explains that “…current anthropological research on emotionality has shown convincingly, emotions and social life are intricately interwoven, which immediately sheds some doubt on the validity of a 11 sharp dividing line between the social and the affective” (Besnier 1990: 431). While not pretending that all expressive meaning is social, I still emphasize the importance of this link (cf. Besnier 1990: 431). Most studies that relate to expressive or affective meaning are studies in cultural ‘emotion lexicons’. These studies recount the names, meanings, and associations (including other affective associations) present in a given sociocultural context. Scholars have well documented emotion as an important part of the lexicon (Besnier 1990: 422) and it is through these studies that many argue the point of culturally specific emotions. Heelas mentions that while “emotion talk”—most often analyzed through emotion lexicons—are “clearly a product of human imagination”, he acknowledges that it “does not have imaginary consequences” (2007: 31). “It in fact has great bearing on the nature of emotional life” (Heelas 2007: 31). He maintains that how people will respond behaviorally—or linguistically—rests on the knowledge of emotional life, because our emotional understanding of a social drama or interaction is enveloped in the understanding of the emotion (cf. Heelas 2007: 32). A person’s emotional interpretation of an event binds itself dialogically in the interpretation of the emotion and the interpretation of the emotion is most often bound up with notion of the word. This is where the lexicon gains its principle significance. Vehicle of some of these lexicons are national languages and “researchers [have] discover[ed] that all speakers of a language share a cognitive structure for emotion” (Kovecses 1990, 2000; Wierzbicka 1999; cited in Boellstorff & Lindquist 2004: 437). Besnier explains that “emotions are not just psychological phenomena but also interactional phenomena, and to demonstrate that emotions are not confined to the local, the intimate, and the personal, but are also relevant to large-scale dynamics such as public life, historical change, and global processes” (Besnier 2011: 434). The shared cognition and the interactional nature of affect gains 12 more pertinent significance when turning to the case of Indonesia. For while people speak hundreds of languages in the country of Indonesia there is an aspect that they share transnationally in societal sense, but also individually in a cognitive sense by speaking Bahasa Indonesia.7 Although I have mostly spoken about the emotion lexicon as a center of affect in language, I would like to emphasize that “affect…permeates all utterances across all contexts because the voices of social beings, and hence their affect, can never be extinguished from the discourse (Besnier 1990: 433). That is, affect (and the sociality of it) pervades all aspects and levels of language whether there are sounds, words, phrases, discourses, or the languages as a whole in question. In this investigation, I look at lexical mapping of emotion and language ideology. Besnier calls for ‘ethnographies of emotion’ stating that “[i]nvestigations of the role of affect in language cannot proceed without a fine-grained ethnographic inquiry into language use in context. Questions that must be addressed include: Who uses which affective tools, for what purpose, in what context, and what role does affect play in the linguistic representation of symbolic processes?” (Besnier 1990: 437). Anthropologists should also direct their attention to matters of nationalism and globalization. “Nationalism is perhaps the most obvious example of how affect is organized within decidedly non-local communities” (Boellstorff and Lindquist 2004: 439; cf. Anderson 1983). The question here is, what is the role of the state and mass media in transforming subjectivities and emotional landscapes? (Boellstorff and Lindquist 2004: 439). Through these questions, this study gains greater significance. For although few have written ‘ethnographies of affective language’, here I parse two principle ethnographies and a few other associated texts, forming an ‘ethnology of affective language’ through the comparison of the 13 Javanese and the Toraja under the Sukarno-Suharto political era—that is, two different cultures and societies under one macro-sociocultural structure. I address the affective tools that former Presidents and their governments used, for what purpose they used them, in what context they used them, and the role that affect played in the linguistic representation of symbolic processes of power. Here I look at local cases of emotion lexical items and language ideologies in order to enlighten the understanding of the behavior and emotions of those people as exhibited through language in the transnational context. In this study, I rely mainly on two ethnographies, Saya S. Shiraishi’s Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics in understanding the Javanese case and Toby Alice Volkman’s ethnography Feasts of Honor: Ritual Change in the Toraja Highlands for the Toraja case. In both cases, to answer that primary question ‘what do Indonesians do when that father-figure is not so fatherly?’, I found that people revolt, not to overthrow the system, but to return the system to a state of order, so that balance in society persists. In Java, this notion comes through in language where if bapak is not behaving as bapak should, he can be replaced; however as opposed to the West, the hierarchy between bapak and adik, President and citizens, authority and constituents does not change or reduce itself. The hierarchy is part of the maintenance of order. The crux of order, in this case the hierarchy, predicates itself on the culturally specific notion of malu (bahasa Indonesia), an emotion of honor-shame, which supports the respect that hierarchy creates. People also convey this linguistically demonstrating the case that the emotional responses to a social condition, in this case the ‘milieu of hierarchy’, predicates itself on the lexical notion of the emotion. In Java, following Shiraishi, the use of kinship terms and the affective impression with which they are infused reifies the hierarchy and maintains social order. The irony is that this language does not 14 remain simply a reflection of how society actually is, but becomes a verisimilitude of social order behind which power hides its atrocities. This is the case of kinship terms as it develops under Sukarno and emerges in full force under Suharto. Bahasa Indonesia itself as a language that becomes thoroughly embedded with this dyadic hierarchy—bapak-adik, president-citizens, authority-constituents—in turn becomes an index of societal order leading to the social perception of it as a highly-valued, elegant, upper register form of speech. For the case of the Toraja, there is no evidence of the effects of kinship-terms political speech on society and I suspect that this gap is not accidental. Although it is conceivable that no one has written on this topic yet specifically with regard to Toraja, I think that effects kinship do not truly apply, because Toraja was never really part of the ‘family’ from the beginning. Taufik Abdullah, an Indonesian historian, uses the metaphor of the “family album” where people go to find their portraits in the book of national history (1993; cited in Atkinson 2003: 136). From my investigation, it appears that the Toraja do not have a portrait in the album. While the Toraja do interact with the Sukarno-Suharto government, it is more from the position of the outside. The kin reference only applies to those inside at the family house inside the familial ‘courtyard’, not to those outside the ‘courtyard’. Since the period of Dutch colonialism Indonesia has divide itself into the Inner Island and Outer Islands. The Inner Island, historically, is Java as this was the center of Dutch organization and control. The Outer Islands were those on Java’s periphery were Dutch control was not as strong. I hold that because Toraja faces a different situation under the Dutch and because of its geographical and cultural distance form Java, while the government would recognize no difference, in practice Toraja is outside of the familial scope, outside of the range of the lens, and thus outside of the family album portrait. For this reason the kin charged language is expelled; however I still analyze the interface between language and affect in the 15 Toraja case. Just as the Javanese kinship-based hierarchy, the Toraja interaction with the government predicates itself on notions of respect, honor, and shame known as siri’. I analyze this culturallyspecific emotion from the local context to understand how it functions in the transnational one. I found that when people revolted in Toraja, it was due to governmental disregard of siri’. Revolts occur not to overthrow the system, but to return the system to a state of order by restoring siri’, so that again balance in society persists. Errington notes that people have said, “It is far better to die with siri’ than to live without it” (1989: 119). Siri’ becomes an emotion that is not only expressed lexically, but also though language ideologies. Disdainful notions of the Toraja language with respect to Bahasa Indonesia which, as I stated above, has become an index of societal order leading to its social perception as upper register form of speech, demonstrates underlying notion of siri’ as the local language and people face the transnational language and people bound up in notions of the primitive world facing the modern world. In both cases the idea is to enlighten the understanding of language and affect as it meets the contemporary social world. As Wilce states, “Emotion mediates between the embodiment of “individual and group agency in…social life” (Lyon 1994:101; cited in 2009: 33). I add that readers must recognize that this social life consists of a micro- and macrocosm, a local and transnational world. Dialogical Formation and Praxis of the “Family” Ideology The formation of the Indonesian family ideology, like most Indonesian national cultural traditions, has its roots in Javanese cultural traditions. Bowen writes concerning Benedict Anderson's work on Indonesian Politics,"[He] discerns the shadow of Javanese structure, history, and idioms underpinning Indonesian and nationalist modes of expression” (Bowen 1994: 1001). 16 In this light, as I parse the 'Indonesian' notion of the political 'family' and its attached emotional profile, I will also show the Javanese kinship system with its emotional profile as it underlies the Indonesian national ones. Historically the use of kinship in the political sphere began in Java which is no surprise. It is not inconceivable for the center of Dutch colonial power in Indonesia to be the center of anti-Dutch colonial resistance. The origins of this kekeluargaan or ‘family-ism’ ideology draw from the “Javanese nationalists” who in the late 1910s endeavored to reconstruct Javanese culture, which they presumed had been lost to colonialism. Suriokusumo, in 1922, established the Committee for Javanese Nationalism which produced a monthly publication Wederopbouw (Reconstruction) (Shiraishi 1997). Suriokusumo stated that his notion of ‘reconstruct’ was meant to restore and rebuild “Javanese ideals of social structure, social morals, and social dignity, which had been lost as a result of foreign rule” (Tsuchiya 1982; cited in Shiraishi 1997). He stated that “[t]hese ideals were conceived of as order, tranquility, prosperity, and good fortune in society, and the unity of kawula and gusti [master-god and servant] in human relations” (Tsuchiya 1982; cited in Shiraishi 1997). They felt that the kawula and gusti was the essence of Javanese culture which was what they lost with the advent of the Dutch. It is from these roots that the bivalent hierarchy evolves into the notion of family, the kinship vocabulary, and the ideology of family in politics. The Indonesian language was also born out of an initially Javanese resistance to Dutch colonial rule. It is under these conditions, an anti-colonial context, where people see the birth of a unified ‘Indonesian’ people and nation-state. Anderson mentions that “[t]he People, newly conceived as a political entity in opposition to the colonial rulers, were to inherit …and, at the same time, to subject themselves, by the crucial mechanism of recognition, to the modalities of a now updated international law (Anderson 1998: 318-319). Here I take that “international law” 17 not only to mean statutes of global organizations (e.g. United Nations, international trade laws, etc.), but more importantly, the habits of the modern world—the most pertinent of which being, first, the ‘nation-state’ and, second, the transnational processes that pan that geopolitical construct. Anderson notes: The major public function of Indonesian has lain in its role as national unifier. Through it began to play this part in the 1920s, it is not until the Japanese occupation that it formally became the language of the state, to be taught in schools and used in offices as a matter of official policy. During the Revolution of 1945-49 it was the language of resistance to the returning Dutch and the language of hope for the future. The Revolution also accelerated the process of filling Indonesian with the emotionally resonant words that give any language its cultural identity and aura, and that seem to express its speakers’ most vital experiences…(Anderson 2009: 271). The primary function of Indonesian was as much resistance of colonialism as it was hope of modernity (cf. Anderson 2009: 271). Crucial words Rakyat (the People), merdeka (freedom), perjuangan (struggle), Pergerakan (the Movement), kebangsaan (nationality), kedaulatan (sovereignty), semangat (dynamic spirit) and revolusi (revolution) demonstrate the affective tone of resistance era Indonesian language indexing notions of solidarity and the hopeful prospect of post-colonial modernity (cf. Anderson 2009: 271). But what is important to this investigation and probably the single most important categorical set of vocabulary in Indonesian—which grew out of this resistance zeitgeist—is the kinship-term system which created an emotionally-charged, post-colonial sense of solidarity. The Indonesian political kinship system is based on a dyadic reciprocal hierarchy. 18 Essentially the higher stratum has as much responsibility to the lower stratum as the lower to the higher. The lower should follow the higher in complete obedience under the presumption that the higher stratum is more mature, developed, and indeed socially realized and thus would know better how society should be. To reiterate this hierarchy indexes notions of social order and connects with notions of social actualization—positions of authority and societal actualization– modernity. In this light, I peer over to Javanese linguistic ideologies where hierarchy is most saliently intertwined. Javanese is the hallmark case of linguistic hierarchy. Javanese social hierarchy expresses itself in the language through the differences between krama which is spoken only by and toward the elite and ngoko which is spoken to people of lower status and among social equals (Bowen 1994: 1001). Aragon mentions that anthropologist Clifford Geertz and James Peacock portray “the language, cosmology, politics, and aesthetics of Indonesia’s most populous ethnic group, the Javanese, [as] revolv[ing] around a dualism that contrasts the refined (alus, Javanese; halus, Indonesian) with the coarse or crude (kasar, Javanese and Indonesian)” (2011: 15). Emerging from this Javanese ideology is the modern practice where language in present-day Jakarta has bifurcated into Indonesian becoming the “new krama” and popular urban style becoming the “new ngoko” (Bowen 1994: 1001). Sociocultural ideologies which become language ideologies influence the lexicon and the use of the language itself in Indonesian. This is where language ideology gains greater significance. After noting how sociocultural ideologies and practices evolve into language ideologies and practices, claims that language ideologies are “secondary rationalizations” as Franz Boas asserted weaken (cf. Wilce 2009: 70). Scholars have discovered that “language ideologies actually influence the evolution of linguistic forms and practices” (Wilce 2009: 70). That might explain the shorten use of bapak (father) and ibu (mother), pak (sir and mister) and 19 bu (miss) in daily Indonesian speech—forms that are on par with the ideologies of family-ism and dyadic reciprocal hierarchy that I afore mentioned. As Ong writes “[f]ollowing Foucault, …power…operat[es] strategically in everyday action and discourse” (1989). These language ideologies afore described have affect mapped on to them. And as I stated above, all of the emotional and structural underpinnings of the kinship terms, Indonesian family ideology, and the status of the language itself derive themselves from Javanese notions of language, hierarchy, and affect. Affect, Language, and Hierarchy in the Javanese Household Almost every aspect of traditional Javanese culture relates to social status. In addition, Geertz notes that “a Javanese perceives such status situations in terms of special, accepted definitions of the “respect” called for and the kinds of feeling-states thought to be appropriate” (1959: 225). The Javanese disapprove of strong emotional expression and always present themselves in a way that is controlled and orderly. Order is center to the Javanese life. “There is a pervasive orderliness in their lives; their persons and property are always clean and well kept” (Geertz 1959: 225). The emotions Iklas which describes “a desirable state of mind in which one gives up something without caring, and in which one is simply resigned to one’s fate” (Geertz 1959: 225) is connected with this cultural notion of order. Although the Javanese endeavor to hide emotions in a sort of passivity, they are always circumspect for any shocking occurrence that may disturb social order. Geertz outlines two principle emotions connected with shocking disorder: bingung and kagèt. Bingung describes “a feeling of mental confusion, of being mixed up, upset, lost”; “losing one’s sense of direction or one’s control of one’s whereabouts, “not knowing which way is north”” (Geertz 1959: 225). Kagèt is the feeling of being “suddenly startled or shocked by something that happens outside of one, so that one becomes disoriented, 20 or bingung” (Geertz 1959: 225). These are apparently very threatening emotions in Javanese culture; however they also function to maintain social distance between people of different statuses. As young Javanese are socialized into the sort of emotional profiles for manipulating family life that the Javanese require one to take on in order to be considered an adult, a person, and indeed a Javanese, one must learn to regulate emotions along the lines of urmat and adji. Geertz translates both as “respect” (Geertz 1959: 229). While mothers are the source of trisna or “love” in family life, fathers only have to seneng or “take pleasure” in their children. Also from the perspective of the child, children are required to show love to their mothers, but should show only respect their fathers. Geertz notes, “She [the mother] is seen as a bulwark of strength and love to whom one can always turn, in contrast to the father, who is distant and must always be treated respectfully”. Children treat their fathers almost with the seemingly same emotional distance as an outside, but submit to him under the presumption that he has their best interest in mind. This “respect” predicates itself affectively on three degrees of “shame”: wedi, isin, and sungkan. Wedi “means “afraid” in both the physical sense and the social sense of apprehension of unpleasant consequences of an action” (Geertz 1959: 231). Isin describes a “fearful reaction, especially to strange things” (Geertz 1959: 229). 8 Sungkan “refers to a feeling of respectful politeness before a superior of an unfamiliar equal, an attitude of constraint, a repression one’s own impulses and desires” (Geertz 1959: 229). These are the three emotional components of respect in Javanese culture. Here Geertz describes how these components interact as the children develops and becomes socialized into the Javanese emotional profile: [the] father…begins to act like an “outsider” toward [the child], and to expect him to behave in his presence according to the social forms appropriate to outsiders. 21 The child finds himself now feeling isin in front of his father, and being told, moreover, to be sungkan in his presence (Geertz 1959: 234). This notion of “respect” and its affective impressions, especially isin, present in the Javanese father-child relations have influenced the Indonesian bapak-adik relationship and forms the basis of that dyadic reciprocal hierarchy and that kekeluargaan ideological family-ism described earlier. In Indonesian, these affective impressions are summed up in the term malu (BI). Malu (honor-shame emotion) is the social glue of that reinforcing skeleton of “respect” on which the dyadic hierarchy predicated itself. Kinship and Affective Language in Java during the Sukarno-Suharto Political Era Sukarno and Suharto use the dyadic reciprocal hierarchy and the kekeluargaan ideological family-ism infused in Indonesian in order to maintain a sense of order in Indonesian society, sometimes to even if this order is only verisimilitude. I would have readers recall the “Guided Democracy” of Sukarno that the government deemed as ‘order’ and Suharto’s killings which were supposedly part of the maintenance of “New Order”. This political rhetoric using kinship terms reinforced order derived from hierarchy present in the language which grounds itself in the affective profile of bahasa Indonesia and thus Indonesians. In Saya Shiraishi’s work Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics, she uses two important contrasts in vocabulary to demonstrate the pervasive dyadic hierarchy and the affective associations connected with each aspect derived from the initial family metaphor. The first is the relationship between antar and bawa. Both mean “to bring someone to some place” except that antar has more of a sense of “legitimate escorting” and “accompanying” while bawa means more “to take by force or illegally”. The words penangkapan and penculikan possess the same sort of relationship with each other as the words antar and bawa. Both mean to detain, expect 22 that penangkapan means more “to arrest” and penculikan means “to kidnap”. In the mid1960s at the fall of Sukarno and the rise of Suharto, Sukarno and a number of high ranking generals were kidnaped (penculikan). They were taken (bawa) by the revolutionaries, who were actually their very own men, lower officers, the military/governmental adik. The revolutionaries took the officers from their homes under the disguise of an arrest (penangkapan) acknowledging the hierarchy. Suharto, during this time of social disorder, steps in and declares that Sukarno was no longer taken (bawa) by force or kidnaped (penculikan), but had been “brought to safety”. President Sukarno was, in this way, escorted (antar) to safety. Since Suharto stepped in to preserve social order, he became as Heider would call him, the ‘agent of order’ (cf. 1991a). Heider in an analysis of Indonesian Cinema noticed that films did not portray evildoers or disrupter to social order as intrinsically nefarious as is done in the West, but rather “agents of disorder”. It is a case that regretful events must occur, but “woe unto the one by whom they come”. ‘Agents of disorder’ unlike Western ‘antagonists’ may be converted and can be made to restore order—there is no need for their removal and replacement, for only permanently unalterable agents need be completely eliminated. While Sukarno was removed, the ‘persona of the position’ was not. In this way, the dyadic hierarchy between President and citizenry, between bapak and adik was maintained. Suharto, being the agent of that maintenance, proved himself as bapak and this filled that ‘persona of the position’ as President. He proved by restoring social order that he knew what was best for the Indonesian people and thus the citizens owed him respect, the same respect dedicated to a father affectively reinforce on malu (BI) honor-shame.9 Through this newly found power in kekeluargaan-derived dyadic hierarchy, Suharto served as President for thirty-two years despite his nefarious deeds. Structure of Family-ism-Derived (Kekeluargaan) Dyadic Reciprocal Hierarchy 23 Engaging ‘Outside the Courtyard’: Affect and the Toraja in Sukarno-Suharto Era Politics As I afore mentioned in regard to the case of the Toraja, there is no evidence of the effects of kinship-termed political speech on the social context. I discovered that in Java, an ideology of kinship, kekeluargaan served as the foundation for a dyadic reciprocal hierarchy that pervaded the Indonesian lexicon of the Javanese and Javanese language use based on social contexts of respect build on malu (honor-shame). There is no sign of this same sociocultural process occurring in Toraja. I suspect that this break in evidence is not accidental, because Toraja was never really part of the ‘family’ from the beginning. Political leaders would deny such a statement, but in practice Toraja is ‘outside of the family courtyard’, outside of the family household. While readers will observe overlap with some of the cultural concepts presented in the Javanese system, the Toraja case, I have discovered, had its own system for engaging with the Sukarno-Suharto era government. 24 Before I begin, I would like to discuss what I mean when I write Toraja. Here, in describing ‘New Order’ Toraja, I pull the core information of my analysis from Tana Toraja written in Toby Alice Volkman’s Feasts of Honor: Ritual and Change in the Toraja Highlands; however I also reference cultural continuities that pervade all Toraja groups and also, when engaged with it, the island of Sulawesi as a whole in the areal-regional culture sense. When not specifically speaking of Tana Toraja, I describe the cultural connects and continuities that apply (or most likely apply) to Tana Toraja as it engages with the ‘outside’. One reason for cultural sharing in a regional sense might due to the Sulawesi linguistic situation. As Mills points out that “[t]he languages—or better, dialect groups—include Buginese, Makassarese, Mandar, Sa’dan Toraja, Pitu Ulunna Salo, Seko and Massenrempulu’…[i]n an area like …Sulawesi where all the languages have been in prolonged and intimate contact with each other, the decision as to what is a “dialect” and what is a “language” is often difficult (1975: 205). I would argue that seeing the influences that language and thus people have had on each other, it is not unfair to imagine Sulawesi as a cultural region where real continuities apply. With that said about the evidence, I return to the primary inquiry of this study, what do Indonesians do when that father-figure is not so fatherly? How do they trust such a ‘patronizing paternal’ figure? Well again, seeing that the kinship ideology does not really apply here, I must reframe the question as, what do Toraja do when a national leader does not support the entire nation as he should? As I previously stated, if the authority does not fulfill its responsibility, people revolt. The revolution, however, does not lead to the overthrow of the system, but returns the system to a state of order with someone else who does fulfill their duties, so that balance persists in society. This social order rests on respect-dependent hierarchy which is reinforced by the honor-shame emotion. In Indonesian, this emotion is referred to as malu, but in Toraja, it is 25 called siri’.10 Hierarchy based on respect through siri’ is central to social order in Toraja. Errington notes that people have said, “It is far better to die with siri’ than to live without it” (1989: 119). Before I go any further, I will exhibit how hierarchy works in the Toraja sociocultural and linguistic context. After reading these two experiences below, it seemed to me that hierarchy impacts both what one would say and expect to be believed and how one would say whatever that he or she would wish to be believed. Volkman writes: Related to this concern with completion is a concern with something like “truth” (tonganna). When anthropologist Shinji Yamashita visited our house and told a version of a myth from southern Toraja, Mama’ Agus [informant] remained politely silent, as she told me later, although she knew that he was “wrong”. But when a Toraja Protestant minister gave me a poetic, rather formal version of a myth that Mama’ Agus herself could tell with far more eloquence and with, she refused to repeat her own account, insisting that I now had the “true” story from the minister, a yonder man of great prestige…(1985: 15) This excerpt demonstrates how, for the Toraja, truth is predicated on power and status. This next excerpt even further accentuates this point, when Volkman writes: When I began fieldwork I had been advised by a social scientist with experience in Sulawesi that to talk directly to “small people” might alienate not only those important, “bigger” people above them, but even the poor and former slaves themselves. To begin at the top, presumably, would earn me the respect and confidence of people at all levels. However, the bonds between the Toraja leaders and followers, high and low are relatively weak. In spite of my position as a “daughter” in a high-status family, few lower-status people seemed drawn or 26 compelled to speak to me for this reason. More commonly such people answered questions with a repeated “I don’t know”: in the hierarchical organization of knowledge, they were not expected to “know.” Once an old woman, a former slave, cried out in exasperation: “Why are you asking me? You’re questioning a cat! (1985: 18-19) Those above demonstrate how hierarchy impacts what one would say and expect to be believed, but the excerpt below gets at how hierarchy impacts how people would say whatever that they wished to be believed as Volkman writes: We had studied Indonesian (bahasa Indonesia) in the United States, and once in Rantepao we began to study the Toraja language, sometimes referred to as bahasa Tae’. This was not, however, and ideal situation, since most people in Rantepao also speak excellent Indonesian and were not inclined to speak their “oldfashioned” language with Americans, especially with a doctored (Ph.D. candidate). Our Toraja tutor, a judge in Makale, was teaching his three year old daughters only Indonesian, believing that in the future it would prove more useful to them than their native tongue. The attitudes and contradictions revealed here were perhaps more significant than the actual Toraja language training… (1985: 9). This excerpt reveals something about language attitudes and use—how people perceive a specific language. Both reveal something about Toraja attitudes as expressed though language. The Toraja communicate affective messages just as much by changing to a totally different language as by changing what they express to whom. In other words, I see the two ideas as connected and coming out of affect. I see these vehicles of social power as being created and reinforced at the same time by affect, taking root there in daily life. Truth and the social trust 27 derived from it are based on the ‘order’ that hierarchy grants. Hierarchy is attached to the emotional life due to people’s idea of social order. The problem with this dependence on hierarchy derives from Toraja’s position in the transnational hierarchy. Their status is not even as adik or citizens, but as those “outside of the courtyard”, those outside of the family. The Toraja just as other many other ‘outer island’ peoples are viewed with a sense of ‘backwardness’ or barbarism from the perspective of the center, essentially Java. Jane Atkinson's work in Sulawesi (2003) describes the exoticizaton and marginalization of upland peoples due to ethnic and cultural stereotypes. Mission-ethnographers Adriani and Kruyt once wrote: In the wild mountains…there still live many Toraja, who are designated by the name To Wana, "forest people". They are, however, none other than To Ampana who, adverse to all rule and coercion, remain roaming the mountains. (Adriani and Kruyt 1914: 74; cited in Atkinson 2003: 15-151) The Toraja do not automatically have a place in the family or in the nation, they must make a name from themselves or prove that they are on par with what the center deems as “Indonesian”. An instance is when Suharto came into power he opened Sulawesi into the national and global economic sphere. One of the products of Sulawesi was traditional art; however this excerpt demonstrates how the Toraja had to adjust their work for it to gain similar prestige and status as the arts of cultures closer to the “center”: Usually Balinese carvings get the label “art” (kesenian, BI), but Toraja carving just get dismissed as “handicrafts” (kerajinan tangan, BI) or “ornaments” (hiasan, BI). We are putting frames around our carvings so people won’t see Toraja things just as ornaments, but rather as art or paintings (lukisan, BI) suitable for the rich. Torajas are considered ‘outside of the family’. This marginalization based on an idea of 28 barbarism arises from two cultural differences with the Toraja: one is religion and the other is language. While Christianity is pervasive in Toraja, traditional practices known as adat still persist. Part of Indonesia’s definition of nationhood and modernity is the adoption of a single world religion. The practice of adak contributes to the idea of less social actualization for the Toraja, for adat represents the pre-modern world. Languages in Toraja are also really different from Indonesian and their use references a step back from nationhood. Indonesian as the national language is modern and represents social order derived from societal hierarchy, Toraja languages are pre-modern and represent social ‘backwardness’. Young Indonesians continue growing up speaking local languages. Bahasa Indonesia is learned later in schools, through mass media, and in other transnational settings (cf. Argon 2011). Argon mentions that for her fieldwork in highland Central Sulawesi, although her “academic preparation for fieldwork was to study Indonesian”, she still “needed to learn a very different local language [once]…settled in Sulawesi” (Argon 2011). These languages are deemed even by people of Sulawesi are ‘backward’ and ‘incomplete’. Argon mentions that the Tobaku of Central Sulawesi “jokingly” refer to their language basa mata’ meaning literally ‘green’, ‘raw’, or ‘unripe’ language (Argon 2011). Volkman notes that “[t]here is a strong sense among Toraja that anything in progress (unfinished) is “not good” (tae’ pa na melo)” (1985: 15) and the use of Toraja languages represent speech that is belum, or “not yet,” or ‘incomplete’ in sense from the perspective of modernity (cf. Lindquist 2009: 7). It is probably for this reason, that the Toraja tutor and judge would not speak Toraja to Volkman and did not teach his children Toraja. Despite these cultural aspects that push the Toraja to the margins of the transnational realm, they still manage to demand respect through siri’ from that government as in this case under Sukarno. 29 In the 1950s and 1960s, there was a large outbreak of belligerent rebellion in Sulawesi. It supposedly placed the island in a state of anarchy (Errington 1989: 16-17). “It was clear to everyone in South Sulawesi, however, that the fight was about siri’” (Errington 1989: 17). Errington explains that siri’ is was separates humans for animals and that people would die, as they did in the rebellion, for the sake of it (cf.1989). In this case the Toraja demanded the respect of the national government. Despite their position in the transnational hierarchy, the Toraja placed themselves in the national “photo album” on the grounds of the affective impression of siri’ and the moral sensibilities of respect associated with it. The foundation of it all is siri’. Conclusions about Language and Affect in the Social World: Perspectives from the Javanese and Toraja Cases To say that words are indexically related to some “object” or aspect of the world out there means to recognize that words carry with them a power that goes beyond the description and identification of people, objects, properties, and events. It means to work at identifying how language becomes a tool through which our social and culture world is constantly described, evaluated, and reproduced (Duranti 1997:19; cited in Ahearn 2012). Language and affect are invariably intertwined as language functions within both the individual and the social, the subjective and intersubjective worlds. This study has focused on the affectively-charged language used during the Sukarno-Suharto era. Specifically with the use of kinship and relational terms in the Indonesian political sphere—that is, both Presidents being referred to as bapak (father) and the Indonesian citizenry as adik (children)—I raised the question, in view of these ‘fathers’’ histories, what do the children do when that father-figure is not so fatherly? The response is if the person in authority is not properly fulfilling their duties, 30 Indonesian people revolt; however not to overthrow the system, but to return the system to a state of order with someone else who does fulfill their duties, so that balance perseveres in society. It is interesting that this response isomorphically applies to both the Javanese and the Toraja case considering the great cultural distance between the two. Nevertheless, the response is the same, although it has different impetuses in each culture. For the Javanese, it is a matter of the ‘honor-shame’ emotion (isin-Javanese; malu-Indonesian) upon which the sensibility of respect (urmat and adji-Javanese) is mapped. Out of this sensibility, one sees the dialogic formation and maintenance of social ideologies, namely the interconnected notions of kekeluargaan (family-ism) and the dyadic reciprocal hierarchy, exhibited through language and in regard to languages. For the Toraja, even though the kinship terms do not apply to them, because of their position in the national hierarchy—or rather exclusion from the system—they still manage to demand the respect of the government on the grounds of siri’, also ‘honorshame’. These common emotions might have come about due to both cultures having contact with what is historically known as the rise of ‘Indic states’; however that is not the focus here. Another interesting aspect, I noticed, was that both cultures did not endeavor to change the system, but only to transform the agency of the positions from agents of disorder to agents of order. French anthropologist and social scientist Claude Levi-Strauss coined the term ‘sociétiés à maisons’ or ‘house societies’ referring to cultures where certain social structures transcend the importance of the people within. The preservation of hierarchy is central to preserving social order. In this regard, only the glitches in the system must be adjusted.11 In addition, a few other questions arise out of this study. Besnier posed the questions, “Who uses which affective tools, for what purpose, in what context, and what role does affect 31 play in the linguistic representation of symbolic processes?” (1990: 437). I addressed in this essay the affective tools that former Presidents and their governments used, the purpose they use them, the contexts where they use them, and the role that affect played in their linguistic representations of symbolic processes of power. The Presidents used language that anchored into the emotions of its citizenry in order to secure power in the transnational political sphere. Following this, Boellstorff and Lindquist raised the question, “what is the role of the state and mass media in transforming subjectivities and emotional landscapes?” (2004: 439) I respond that the practice of social ideologies in language linked to affect shape and revise the subjectivities and intersubjectives in which emotional landscapes reside whether it is kekeluargaan in Javanese Indonesian or linguistic insecurity due to notions of primitivism and social marginality in Toraja language. Through these questions, this study gains greater significance as an ‘ethnology of affective language’ where individual, local, and global processes meet and define culture. It is important to notice how “language can “point to” something social or contextual without functioning in a referential way” (Ahearn 2012), such as in the way that expressive or affective meaning indexes moral values and sensibilities. In realizing this, one should note that language’s affective function is always a matter of interplay between the subject and the group, the individual and the social. For while Schleifer explains that “[t]he neural bases of human language are intertwined with…aspects of cognition, motor control, and emotion” (Lieberman 2000; qtd. 2001), one must not forget that that the body where these “neural bases” reside lives in a social environment. Notes 1. Note that I have americanized all orthography for visual coherence. 32 2. The word Tapol is the abbreviated form of Tahanan Politik meaning ‘Political Prisoner’. 3. PKI stands for Partai Komunis Indonesia, the Indonesian Communist Party. 4. DPRD is the acronym for Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah which is again the Regional House of Representatives (or Regional People’s Representative Council in direct translation). The Partindo, the abbreviated form of Partai (Nasional) Indonesia, is a Indonesian Nationalist Party which was Sukarno’s political party. Some people also sometimes use PNI to abbreviate Partai Nasional Indonesia. 5. I hold the definition that ‘intersubjectivity’ consists of “the shared feeling[s], mutual understanding[s], [and] mutual attunement; the ground of cooperation, successful interaction, and the co-production of meaning” (Wilce 2009:198) in a given social context. 6. The term ‘subject’ “[f]ollowing Francophone philosophical work on le sujet,…refers to what the Anglophone tradition calls ‘self’ or ‘person’” (Wilce 2009: 200). 7. Bahasa Indonesia literally translates as ‘language of Indonesia’ and is the official national language. I use the words Indonesian, Indonesia language, and Bahasa Indonesia (BI) interchangeably in this essay. 8. There is a congruency between Javanese isin and siri’, the Toraja word for ‘honor-shame’ which I will introduced later. 9. The same congruency applies between Hildred Geertz’s isin and malu (Collins and Bahar 2000: 38). 10. Although there are nuances between malu and siri, here I speak of them as congruent terms of shame due to the way they construct themselves cognitively in related cultures of Western Malayo-Polynesian speakers (cf. Collins and Bahar 2000: 36). Observations of usage reflect this notion: people use the phrase “to know one’s siri’ untandai siri’na (Volkman 1988: 73) in very 33 similar ways as “to know one’s malu’. Also, etymologically, both words share a common ancestry with the words for ‘betelnut’ which is important, due to this product’s connection with hierarchy. Betelnut has been an extremely important commodity throughout Indonesian (and even Southeast Asian) history. Chewing betelnut historically has occurred in many diverse sectors of Indonesian life such as rituals funerals to those of weddings (cf. Reid 1985). However most importantly, betelnut has been traditionally linked to hierarchy as Anthony Reid notes that “[f]rom the earliest descriptions until well into the nineteenth century we learn that no important person left his house with a retainer or slave to carry his betel equipment, a bronze tray with containers for each of the ingredients” (1985: 531). Sirih (suroh- Low Javanese) (cf. Reid 1985)—probably from Sanskrit—are associated with betelnut. In view of this, it is interesting that Malay and Javanese, languages originally spoken in areas that faced the rise of Indic states, derived a similar term. Malu--is the word for betelnut in many other Austronesia languages. (Taber 1993: 412) The connection between betelnut and notions of honor-shame could have possibly been born from the situations like the one described by Reid above in which two seemingly opposing concepts ‘honor’ and ‘shame’ unite. This is also another isomorphic connection, one of semantics, between malu and siri’. 11. The conceptual structure of hierarchy in the house or in the “courtyard”, as portrayed by Shiraishi, may have pre-historical roots. The word for 'house, domicile', family dwelling' reconstructs back to Proto-Austronesian as *Rumaq (Blust 1976; Blust 1980). References Adams, K. M. (2006) Art as politics: Re-crafting identities, tourism, and power in Tana Toraja, Indonesia, Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. 34 Ahearn, L. M. (2012) Living language: An introduction to linguistic anthropology, Malden: Wiley Blackwell. Anderson, B. R. O’G. (1990) Language and power: Exploring political cultures in Indonesia, Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Anderson, B. R. O’G. (1998) The spectre of comparisons: Nationals, southeast asia and the world, New York: Verso. Anderson, B. R. O’G. (2009) ‘The adventures of a new language’, In The Indonesia reader: History, culture, politics, Tineke Hellwig and Eric Tagliacozzo, eds. pp. 271-274, Durham: Duke University Press. Aragon, L. V. (2011) ‘Living in Indonesia without please or thanks: Cultural translations of reciprocity and respect’, In Everyday life in southeast asia, Kathleen M. Adams and Kathleen A. Gillogly, eds. pp. 16-26, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Atkinson, J. M. (1983) ‘Religions in dialogue: The construction of an Indonesian minority religion’, American Ethnologist, vol. 10(4), pp. 684-696. Atkinson, J. M. (2003) ‘Who appears in the family album? Writing the history of Indonesia’s revolutionary struggle’, In Cultural citizenship in island southeast asia: Nation and belonging in the hinterlands, Renato Rosaldo, ed. pp. 134-161, Berkeley: University of California Press. Bell, M. A. and C. D. Wolfe (2004) ‘Emotion and cognition: An intricately bound developmental process’, Child Development, vol. 75(2), pp. 366-370. Besnier, N. (1990) ‘Language and affect’, Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 19, pp. 419-451. Besnier, N. (2011) ‘Review of Language and Emotion’, Language, vol. 87(2), pp. 433-435. Blust, Robert (1976) ‘Austronesian culture history: some linguistic inferences and their relations to the archaeological record’, World Archaeology, vol. 8(1), pp. 19-43. 35 Blust, Robert (1980) ‘Early Austronesian social organization: the evidence of language’, Current Anthropology, vol. 21, pp. 205-247. Boellstorff, T. and J. Lindquist (2004) ‘Bodies of emotion: Rethinking culture and emotion though southeast asia’, Ethnos, vol. 69(4), pp. 437-444. Bowen, J. R. (1994) ‘Review of language and power: Exploring political cultures in Indonesia’, American Ethnologist, vol. 21(4), pp. 1001-1002. Cablitz, G. H. (2006) Marquesan: A grammar of space, New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Carsten, J. (1995) ‘The subsistence of kinship and the heat of the heath: Feeding, personhood, and relatedness among malays in Pulau Langkawi’, American Ethnologist, vol. 22(2), pp. 223241. Causey, A. (2011) ‘Toba Batak selves: Personal, spiritual, collective’, In Everyday life in southeast asia. Kathleen M. Adams and Kathleen A. Gillogly, eds. pp. 27-36, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Cribb, R. (2009) ‘The mass killings of 1965-66’, In The Indonesia reader: History, culture, politics. Tineke Hellwig and Eric Tagliacozzo, eds. pp. 347-351 Durham: Duke University Press. Enfield, N. J. (2010) ‘Without social context? Review of the evolution of language and the evolution of human language: Biolinguistic perspectives’, Science, vol. 329. pp. 1600-1601. Errington, S. (1989) Meaning and Power in a Southeast Asian Realm, Princeton: Princeton University Press. Fox, E. (2008) Emotion science: Cognitive and neuroscientific approaches to understanding human emotions, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Geertz, H. (1959) ‘The vocabulary of emotion: A study of Javanese socialization processes’, Psychiatry. vol. 22(3), pp. 225-237. 36 Good, B. J. (2004) ‘Rethinking ‘emotions’ in southeast asia’, Ethnos, vol. 69(4), pp. 529-533. Grant, A. P. (2003) ‘Review of ethnosyntax: Explorations in grammar and culture’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 4(3), pp. 589. Hanks, J. R. (1964) ‘Reflections of the ontology of rice’, In Primitive views of the world. Stanley Diamond, ed. pp. 151-154, New York: Columbia University Press. Hanks, L. M. and J. R. Hanks (1970) Travellers among people. In In Memoriam Phya Anuman Rajadhon, Bangkok: The Siam Society. Heelas, P. (2007) ‘Emotion talk across cultures’, In The emotions: A cultural reader. Helena Wulff, ed. pp. 31-66. New York: Berg. Heider, K. G. (1991a) Indonesian cinema, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Heider, K. G. (1991b) Landscapes of emotion: Mapping three cultures of emotion in Indonesia. New York: Cambridge University Press. Henry, J. (1936) ‘The linguistic expression of emotion’, American Anthropology, vol. 38(2), pp. 250-256. Hsieh, F. (2011) ‘The conceptualization of emotion events in three Formosan languages: Kavalan, Paiwan, and Saisiyat’, Oceanic Linguistics, vol. 50(1), pp. 65-92. Millar, S. B. (1983) ‘On interpreting gender in Bugis society’, American Ethnologist, vol. 10(3), pp. 477-493. Mills, R. F. (1975) ‘The reconstruction of Proto-South-Sulawesi’, Archipel, vol. 10, pp. 205-224. Ong, A. (1989) ‘Center, periphery, and hierarchy: Gender in southeast asia’, In Gender and anthropology: A critical review for research and teaching, Sandra Morgen, ed. pp. 294-305, Washington, D. C: American Anthropological Association. Panoff, M. (1995) ‘Review of In the midst of life: Affect and ideation in the world of the Tolai’, 37 Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 1(1), pp. 210-211. Reid, A. (1985) ‘From betel-chewing to tobacco-smoking in Indonesia’, Journal of Asian Studies, vol. XLIV(3), pp. 529-547. Reyna, S. P. (2002) Connections: Brain, mind and culture in a social anthropology, New York: Routledge. Robson, S. and Y. Kurniasih (2010) Basic Indonesian: An introductory coursebook, Rutland: Tuttle Publishing. Schleifer, R. (2001) ‘The poetics of tourette syndrome: Language, neurobiology, and poetry’, New Literary History, vol. 32(3), pp. 563-584. Shiraishi, S. S. (1990) ‘Pengantar or introduction to new order Indonesia’, Indonesia, vol. 50, pp. 121-157. Shiraishi, S. S. (1997) Young heroes: The Indonesian family in politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Southeast Asia Program Publications. Smith-Hefner, N. (2011) ‘Javanese women and the veil’, In Everyday life in southeast asia. Kathleen M. Adams and Kathleen A. Gillogly, eds. pp. 154-164, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Sukarno, D. (1965) Sukarno: An autobiography as told to Cindy Adams, Indianapolis: BobbsMerrill Company, Inc. Taber, M. (1993) ‘Toward a better understanding of the indigenous languages of southwestern Maluku’, Oceanic Linguistics, vol. 32(2), pp. 389-441. Vickers, A. (2005) A history of modern Indonesia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Volkman, T. A. (1985) Feasts of honor: Ritual and change in the Toraja highlands. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. 38 Wilce, J. M. (2009) Language and emotion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Winzeler, R. L. (2011) The peoples of southeast asia today: Ethnography, ethnology and change in a complex region. Lanham: AltaMira Press.