- Office of Multicultural Interests

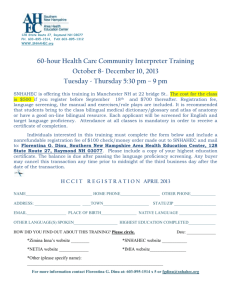

advertisement