IV Drug Use and Retinopathy

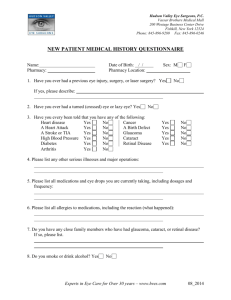

advertisement

POTENTIAL POSTERIOR SEGMENT COMPLICATIONS OF INTRAVENOUS DRUG ABUSE AMANDA S LEGGE, B.S. ABSTRACT CASE REPORT: Two patients present with similar chief complaints: a sudden, painless, decrease in vision that has remained stable for the past few days. Upon dilation, retinal and choroidal infiltrates led to additional questioning regarding social history. Both patients then admitted to intravenous drug abuse for the past 10+ years. The urgency of the situation was stressed and both were referred to a local hospital for cultures and intravenous/intravitreal antimicrobial therapy as indicated. DISCUSSION: Intravenous drug abuse is associated with a remarkable amount of local and systemic complications. Numerous ophthalmological consequences can be observed with or without patient symptoms. Observation of suspicious signs warrants a thorough history including recreational drug use. Eliciting a connection between intravenous drug abuse and clinical signs is important in order to quickly and accurately diagnose and manage both the ocular and systemic complications associated. Injection of intravenous drugs is directly associated with a variety of local and systemic complications. It can have detrimental effects on ocular tissue. The most devastating visual signs include choroidal and retinal nodules, infarction, and inflammation. This is especially true because these lesions typically occur in the posterior pole near the macula. Eliciting a thorough history is crucial for appropriate tests, cultures, and treatment. Prompt diagnosis and management is of utmost importance to decrease both ocular and systemic morbidity and mortality. The following case reports illustrate infections and possible posterior segment consequences secondary to intravenous drug abuse and the management of such. CASE REPORT 1 HISTORY The patient is a 30-year-old white male who presented to our office for the first time with a chief complaint of decreased vision O.S. greater than O.D. The vision decreased suddenly approximately two weeks ago and has remained stable O.U. He denied floaters or photopsia, diplopia, pain, or discomfort. The patient’s medical history is remarkable for posttraumatic stress disorder, bipolar affective disorder, chronic cluster headaches, and depression. He does not take any medications. The patient’s ocular history is unremarkable as he reports never having a formal eye exam. Family ocular and medical history is unremarkable. Prior to vision loss the patient experienced lowgrade fevers, severe cluster headaches, and diffuse joint pain for one month. An extensive lab work-up was performed by his primary care physician (PCP) and all results were within normal limits including CBC, PT/PTT, INR, lupus anticoagulant, amylase, lipase, FTA, rheumatoid factor, ANA, RPR, urinalysis, and HIV screening. He also had a negative CT scan of the head and chest without contrast. He has not seen his PCP since receiving these results. He reports that these symptoms seem to be worsening. The patient admits to intravenously injecting crack cocaine dissolved in vinegar. He admits to using approximately 10 to 15 times per week for the past five years. He states that he is aware of the risks of his behavior but has not attended any counseling or rehabilitation for it. DIAGNOSTIC DATA The patient’s unaided visual acuity was 20/40 O.D. and 10/300 O.S. with direct fixation. No improvement with pinhole. He was 20/200 with eccentric fixation O.S. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light without an afferent defect. Extraocular motility testing found no restrictions of muscle movement. Confrontation visual fields were full to finger counting O.D., O.S. Intraocular pressures via applanation were 11 mmHg O.D. and 12 mmHg O.S. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable. No inflammatory cells or protein flare was noted in the anterior chamber. Gonioscopy O.U. revealed the most posterior structure in all quadrants to be the ciliary body face. No sign of microhyphema, microhypopyon, peripheral anterior synechiae, or neovascularization O.D., O.S. was noted. Posterior segment evaluation revealed multiple choroidal and retinal infarcts of varying duration and Roth spots throughout the posterior pole O.U. Nerve fiber layer hemorrhages and exudates as well as retinal infiltrates were noted, indicating a septic chorioretinitis. The optic nerves were flat, pink, and distinct with no sign of disc edema. Figure 1. Fundus Photography illustrating bright retinal infiltrates, hemorrhages, dull choroidal infarcts O.U. and exudates O.D. Figure 2. Encircled magnified views. Left: Roth spot with obvious infarct surrounded by lighter hemorrhage. Right: Retinal infiltrate upper left and choroidal infarct lower right of the magnified circle. Figure 3. Fundus autofluorescence photograph illustrating the multiple hemorrhages surrounding the white infarcts (Roth spots) blocking the autofluorescence. The macula O.S. was directly affected, correlating with his severe decrease in vision in that eye. The right eye had subtle macular edema and exudates accounting for his mild decrease in vision. Additional blood work was ordered including repeat CBC with platelet count and differential, troponin I, Westergren sedimentation rate, Creactive protein, and a blood culture. This was obtained the same day as presentation. DIAGNOSIS AND FOLLOW-UP A diagnosis of septic chorioretinitis was made. The emergent nature of this condition as well as the suspected underlying cause of bacterial endocarditis was strongly stressed to the patient. An immediate referral was made to a local hospital indicating the need for a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) to confirm the diagnosis and prompt administration of intravenous antibiotics. He did not report to the hospital as recommended. Upon investigation a relative informed us that he had died from a gunshot wound to the head. Apparently he was murdered the night of the referral. This was confirmed. The lab results revealed an elevated troponin I, sed rate, and CRP. CBC was still within normal limits. Blood culture revealed growth of staphylococcus aureus, possibly methicillin resistant. Although a TEE could not be obtained to confirm, a presumed diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis caused by S. aureus was made. CASE REPORT 2 HISTORY The patient is a 42-year-old white female. She presented to the office with a chief complaint of severe blurred vision O.D. for the past week. The vision decreased rapidly and painlessly over the course of two to four days and has remained stable since that time. No complaint of pain, irritation, diplopia, photopsia, or floaters was elicited. She did not have any associated signs or symptoms. The patient’s medical history is unremarkable, but she admitted she has not seen a physician in at least 10 years. Her ocular history is unremarkable. She does wear glasses since the age of 12. Her current prescription is at least 4 to 5 years old. Family ocular and medical history was unremarkable. The patient is an admitted intravenous heroin user since the age of 15. In the past year she has cut back to using only a few times per month. She admitted to using up to six times daily in the past. She stated that she is aware of the risks of her behavior. She has tried multiple counseling sessions over the last 5 years. She has never enrolled in a formal rehabilitation program. DIAGNOSTIC DATA Upon evaluation the patient’s aided visual acuity was 20/100 O.D. without pinhole improvement and 20/20 O.S. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light without an afferent defect. Extraocular motility testing found no restrictions of muscle movement. Confrontation visual fields were full to finger counting O.D., O.S. Color vision was 14/14 O.D., O.S. and no red desaturation was noted. Intraocular pressures via applanation were 18 mmHg O.D. and 19 mmHg O.S. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable. No inflammatory cells or protein flare was noted in the anterior chamber. Gonioscopy O.U. revealed the most posterior structure in all quadrants to be the ciliary body face. No sign of microhyphema, microhypopyon, peripheral anterior synechiae, or neovascularization O.D., O.S. was noted. Posterior segment evaluation revealed a round, yellow-white pre-retinal lesion with surrounding telangiectasia O.D. and 2+ posterior vitreal cells. Trace to 1+ cells were noted in the anterior vitreous. and vitreal inflammation than true disc edema as no afferent defect was noted on pupil testing and color vision was normal. The left fundus was unremarkable. The optic nerve O.D. had blurred margins; however this was likely secondary to traction Figure 4. Color fundus photography illustrating the position of the retinal lesion as well as the blurred disc margins. Few retinal striae can be seen temporal to the lesion. Figure 5. Magnified red-free image of the retinal lesion illustrating the surrounding telangectatic vessels. DIAGNOSIS AND FOLLOW-UP The patient was immediately directed to the hospital for cultures and intravenous antimicrobial therapy. The patient underwent MRI of brain and orbits with and without contrast, FTA, RPR, HIV screening, Lyme titre, ACE, toxocara IgG, PPD, chest XRay and CBC testing as well as blood cultures. A vitreal culture was taken the following day. A mold infection of unknown species was identified in the vitreal cultures. All other testing was negative. The patient was started on amphotericin B intravenously as this is broad spectrum and the exact species could not be identified. The mold has not been reproducing in the mycology lab. This is necessary for species identification. Because amphotericin B has poor vitreal penetration when prescribed orally the patient was also started on 5µg / 0.1 mL intravitreal injection of amphotericin B. She has had 2 intravitreal injections in 5 weeks. The patient was hospitalized for 5 weeks and was released. The patient has transferred from intravenous to oral amphotericin B as managed by her infectious disease specialist. The patient now reports a moderate improvement in vision with mild distortion. Visual acuities were measured to be 20/50 O.D. and 20/20 O.S. Vitreal cells were not observed on this exam. The pre-retinal nodule has now formed a fibrotic scar causing retinal traction and retinal striae. Blood cultures were performed again 2 and 4 weeks after hospital admittance and are still negative. Eight weeks after culture the mold was identified as Malbranchea spp. The patient will be monitored closely for advancing retinal traction and potential for a detachment. She has been well educated on the risks associated with intravenous drug abuse and will begin rehabilitation next week. Figure 6. Fundus photography at 5 weeks after original diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Fibrotic scarring Is now in place of the nodule with moderate traction and retinal striae through the macula and superior vascular arcade. DISCUSSION Recreational injection of drugs is directly associated with a variety of local and systemic complications. It is also linked to the transmission of infectious diseases through needle sharing and sexual activity. The most serious ocular complications have been reported from the use of crack or crack-cocaine, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), or diamorphine (heroin) injections1. Ophthalmological complications include corneal ulcers, reduced corneal sensitivity, microtalc retinopathy, retinal or choroidal infarcts, central retinal artery or vein occlusion, endophthalmitis, nystagmus, and cerebrovascular accidents that cause neuro-ophthalmic manifestations2. Retinal or choroidal infarct, inflammation, or infiltrate cause some of the most devastating visual sequelae as they are typically located in the posterior pole1. These signs are indicative of general septic chorioretinopathy. The underlying cause is bacterial or fungal and less commonly parasitic. Inflammatory causes of chorioretinopathy must also be ruled out. Eliciting a history of illicit intravenous drug abuse is imperative when septic chorioretinopathy is suspected. This aids in prompt testing for the most common pathogens associated with this risky behavior and early initiation of appropriate treatment. The most common pathogen affecting IV drug users is bacterial, specifically Staphylococcus, with the most concerning species being methicillin resistant S. aureus. Other common pathogens include streptococci species, gram negative bacilli, enterococci, fusarium, 2 aspergillus, and candida . A serious presentation of bacterial chorioretinitis in intravenous drug users is Roth’s spots and choroidal infarcts secondary to bacterial endocarditis. Roth spots are white centered hemorrhages that classically are indicative of bacteremia and bacterial endocarditis; however they are also seen in diseases such as leukemia, pernicious anemia, sickle cell disease, and connective tissue disorders3. In bacterial endocarditis, Roth spots are formed as a result of thrombocytopenia and a low grade, disseminated, intravascular 4 coagulopathy . The clinically viewed white centered hemorrhages are most likely caused by anoxia which causes a sudden increase in venous pressure. This causes capillary rupture and extrusion of whole blood. Platelet release causes the coagulation cascade to initiate, eventually causing a platelet-fibrin thrombus surrounded by heme5. Because of this specific pathology, Roth spots are now part of the standard used to determine a diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis6. According to the Duke Criteria, infective endocarditis is definitely present under three conditions: two major clinical criteria are present, one major and three minor clinical criteria are present, or if five minor clinical criteria are present. Major clinical criteria include persistently positive blood cultures for organisms that are typical of causing bacterial endocarditis, vegetations or abscesses in heart valves present on echocardiogram, evidence of new echocardial damage, or culture evidence of infection with Coxiella burnetii. Minor critical criteria include fever, the presence of a predisposing valvular condition or intravenous drug abuse, vascular phenomenon (includes emboli to organs or brain and hemorrhages in the mucous membranes around the eyes), immunologic phenomenon (includes Roth’s spots and Osler’s nodules), and positive blood cultures that do not meet the strict definitions of the major criteria7. Compared to other classification systems, the Duke Criteria has the highest validity. Multiple studies have shown its predictive value to be approximately 80% and it rarely rejects any infective endocarditis that is ultimately pathologically confirmed6,7,8. The patient in Case 1, although unable to undergo further testing, was a probable diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis according to this criterion. A definite diagnosis would have required additional testing including a TEE. Early treatment of bacterial endocarditis is crucial to maintaining low morbidity and mortality rates. Treatment consists of prolonged parenteral therapy of bacteriocidal agents. Serial blood cultures are necessary to document sterilization. In intravenous drug abusers, the most common pathogen causing bacterial endocarditis is Staphylococcus aureus, accounting for over half of these infections9. The most common treatment regimen for S. aureus infective endocarditis is intravenous naficillin and an aminoglycoside for two weeks10. Several studies have also evaluated a regimen of oral antimicrobials for intravenous drug users as many refuse hospitalization. These have not been as successful. Standard of care remains a two week hospitalization period with serial blood cultures11. Fungal infections can also cause choroidal or retinal nodules, infarcts, and inflammation in intravenous drug abusers. However, Roth’s spots are not typical in fungal or parasitic infections. The most common cause of fungal chorioretinopathy in intravenous drug abusers is candida12. It often presents as a round, white, fluffy, lesion with a mild to moderate vitritis. This must be primarily differentiated from toxoplasmosis which is similar in appearance; however the active lesion is often directly adjacent to a chorioretinal scar. Other differentials include tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme disease, sarcoid, and toxocara3. Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis is typically caused first by a chorioretinitis and then progresses into the vitreous. Transient fungemia may seed in the highly vascularized choroid13. Once in the choroid, the yeast proliferates, invokes an inflammatory response and can subsequently rupture into the vitreous cavity. Once in the vitreous cavity the infection is considered a true fungal endoophthalmitis14. Treatment consists of oral antifungals, unless the vitreous is involved. A vitritis in a fungal infection is best treated with early vitrectomy and intravitreal Amphotericin B13,15. An infectious disease specialist should always be consulted once a diagnosis of fungal chorioretinitis or endophthalmitis is diagnosed. The duration of treatment for fungal endophthalmitis is minimally five weeks and is ultimately based on improvement of ophthalmological examinations16. Unfortunately the species of the mold in Case 2 could not be determined during the treatment period and therefore broad spectrum antifungals were utilized with moderate success. Diagnosis of septic chorioretinitis warrants further investigation into a patient’s social history, specifically with regards to any recreational drug use. This is especially true if a patient is in a high risk population for illicit drug abuse. Prompt diagnosis and management is crucial to lowering the ocular and systemic morbidity and mortality associated with these findings. Comanaging with an infectious disease specialist early in the treatment course is advised. Patient education and rehabilitation services should be offered and encouraged immediately following any hospitalization requirements. REFERENCES 1 Firth, A., Ocular Sequelae from the Illicit Use of Class A Drugs, Br Ir Orthopt, 2004; 1: 10-18. Cherubin, C., Sapira, J., The Medical Complications of Drug Abuse and Assessment of the Intravenous Drug User: 25 years Later. Annals of Int Med., 1993, Nov; 119(10): 1017-1028. 3 Wills Eye Hospital. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott; 2008. 4 Ling, J., James, B., Classic Signs Revisited: White Centered Retinal Hemorrhages (Roth Spots). Post-grad Med J, 1998; 74: 581-582. 5 Urbano, Frank, Review of Clinical Signs: Peripheral Signs of Endocarditis. Hospital Physician, 2000, May; 41-46. 6 Durack, DT, Lukes, AS, Bright, DK., New Criteria for Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis: Utilization of Specific Echocardiographic Findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med, 1994: 96:200. 7 Li, JS, et al., Proposed Modifications to the Duke Criteria for the Diagnosis Infective Endocarditis. Clin Inf Dis, 2000; 30:633. 8 Hoen, B, et al., Evaluation of the Duke Criteria versus the Beth Israel Criteria for the Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis, 1995; 21:905. 9 Mathew, J., et al., Clinical Features, Site of Involvement, Bacteriologic Findings, and Outcome of Infective Endocarditis in Intravenous Drug Users. Arch Int Med, 1995; 155:1641. 10 Chambers, HF., et. al., Right-sided Staphylococcus aureus Endocarditis in Intravenous Drug Abusers: Two Week Combination Therapy. Ann Intern Med, 1988; 109: 619. 11 Heldman, AW, et. al., Oral Antibiotic Treatment of Right-Sided Staphylococcal Endocarditis in Injection Drug Users: Prospective Randomized Comarpison with Parenteral Therapy. Am J Med, 1996; 101: 68. 12 Klotz, SA, Penn, CC, Negvesky, GJ, Butrus SI., Fungal and Parasitic Infections of the Eye. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2000; 13: 662685. 13 Aguilar, G., Blumenkrantz, M, Egbert, P., McCulley, J., Candida endophthalmitis after intravenous drug abuse. Arch Ophthalmol, 1979; 97(1): 96-100 14 Omuta, J, et. al., Histopathological Study on Experiemental Endophthalmitis Induced by Bloodstream Infection with Candida Albicans. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2007; 60: 33. 15 Essman, et. al., Treatment Outcomes of a 10-Year Study of Endogenous Fungal Endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers, 1997; 28: 185. 16 Popovich, et. al., Compliance with Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for Ophthalmic Evaluation of Patients with Candidemia. Infect Dis Clin Pract, 2007; 15: 254. 2