Pediatric ECG cases

advertisement

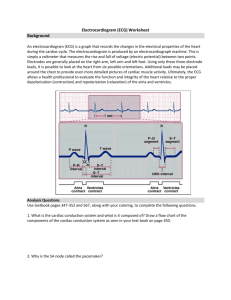

1 Pediatric ECG Cases: Benign Variants or Life-Threatening Abnormalities? Although most physicians are familiar with the normal limits of ECG intervals for adults, it may not be immediately apparent that children have different normal values. Population studies have helped to formulate generally accepted normal values for children at various ages,[1] which should be referenced when interpreting an ECG. However, even with these values, it may be difficult to make a diagnosis. Variation occurs in children depending on age and sex, but most pathologic conditions fall well outside the range of normal. See whether you can determine whether the ECGs in the following cases are benign variants from the norm or cause for concern. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. 2 A 16-year-old male is brought to the emergency department (ED) with chest pressure and mild dyspnea. His 12-lead ECG is shown. This is not the first occurrence, but it is the first time he has brought it to the attention of his parents. There has been slight exercise intolerance. On examination, his blood pressure is 108/50 mm Hg and his heart rate is approximately 60 beats/min and regular. He has a nontender chest wall. What is the next step in the patient’s management? A. Prepare for possible transcutaneous pacing B. Administer intravenous atropine at 0.02 mg/kg C. Do nothing, because this is a benign pediatric ECG finding D. Begin amiodarone therapy E. Admit for electrophysiology study 3 Answer: C. Do nothing, because this is a benign pediatric ECG finding This ECG shows an ectopic junctional rhythm. Note the regular rhythm with an absence of P waves (purple arrows). Retrograde P waves can sometimes be found just after the QRS complex or slightly buried in the T waves. In children, a junctional rhythm is most often a benign finding. It may be caused by acute stressors, such as infection, oxygen desaturation, and stimulation of the vagus nerve. This patient’s rate increased appropriately with a short trial of exercise in the ED. Despite some prominent precordial QRS complexes, this patient does not have left ventricular hypertrophy. It would be reasonable to arrange for outpatient follow-up with a pediatric cardiologist.[2] 4 A 15-year-old male experienced a syncopal episode during his first high school basketball game. He was brought to the ED by ambulance for evaluation. His ECG is shown. Recognizing the potential abnormality, you advise the patient to avoid participating in any strenuous activity until he receives a full evaluation from a cardiologist. What structural abnormality is suggested by the ECG shown? A. Accessory pathway B. Ventricular septal defect C. Ebstein anomaly D. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy E. Anomalous coronary artery 5 Answer: D. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy The ECG shows prominent septal R waves in V1 (blue arrows) and septal Q waves in anterior leads (red arrows) and lateral leads (V3-V6), which are consistent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with characteristic septal hypertrophy. On examination, a characteristic systolic murmur that decreases with squatting and increases with the Valsalva maneuver or tight hand grip, is expected. Definitive diagnosis is made by echocardiography, which should be obtained in anticipation of pediatric cardiology evaluation. Initial medical management is often focused on maintaining adequate hydration and beta-blockade. With syncope, it is important to discern outflow obstruction from ventricular arrhythmia, often by exercise echocardiography. Amiodarone can reduce the incidence of sudden cardiac death.[3-5] 6 An 11-year-old girl from Martha’s Vineyard is being evaluated at an outpatient pediatric clinic for low-grade fever and exercise intolerance on the soccer field, which manifests as easy fatigue and generalized weakness. Her 12-lead ECG and magnified rhythm strip are shown. Until recently, she has been completely healthy and developing normally and has had no palpitations, chest pain, syncope, or exercise intolerance. There are no cardiac medications in the household. What is the next step in management? A. Do nothing, because this is a benign pediatric ECG finding B. Obtain an echocardiogram to evaluate for congenital heart disease C. Begin transcutaneous pacing immediately D. Obtain Lyme disease serologies E. Begin isoproterenol therapy 7 Answer: D. Obtain Lyme disease serologies This child has presented with first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, as evidenced by the markedly prolonged PR interval of approximately 310 ms. This is most often a normal variant in the pediatric population as a result of increased vagal tone, particularly in runners. Asymptomatic first-degree AV block often requires no further workup or treatment; however, many congenital, infectious, immunologic, or toxicologic conditions may also cause prolonged PR intervals. This patient comes from an area where Lyme disease is endemic. Lyme disease can present with heart block ranging from first-degree to complete. In this patient, Lyme titers were positive, and she was treated with a course of doxycycline. Repeated ECG several weeks later demonstrated a return of the PR interval to a normal value.[6] 8 A 12-year-old male athlete is brought to the ED by his parents after he experienced chest pain. Upon arrival, he has reproducible chest-wall tenderness. The parents insist that he receive an ECG because a local middle-school athlete recently died during a sporting event. The ECG is noted to be “abnormal” by the machine (and the concerned parents). What is the next step in management? A. Obtain at least 2 sets of cardiac enzyme values B. Obtain cardiology consult in the ED C. Refer for 2-dimensional echocardiography D. Reassure the patient and his parents E. Admit for observation 9 Answer: D. Reassure the patient and his parents The 12-lead ECG shows T-wave inversions in the right precordial leads (red arrows); these are normal findings. The T-wave morphology in V1-V3 is dynamic throughout childhood. Newborns up to 3 days of life will have upright T waves in V1, but this lead will invert within the first week of life. T waves in leads V2 and V3 also invert in early childhood; in fact, upright T waves at a young age may be abnormal. They will progressively become upright in most children in the order of V3, V2, and V1 by the teenage years. This conversion is already becoming evident in the preteen patient, as V3 has a nearly flat to biphasic T wave.[3,7] 10 6-year-old girl is found to have a systolic murmur on routine examination at the pediatrician’s office. Her 12-lead ECG and magnified rhythm strip is shown. The family just moved to the area, so this is the first time the child has been examined by this physician. There is no documentation of a murmur in the records transferred from her previous pediatrician. Thus, the child is referred for a routine cardiologic evaluation. What is the most appropriate interpretation? A. Atrial fibrillation B. Sick sinus syndrome C. Second-degree Mobitz type I AV block D. Premature atrial contractions E. Sinus arrhythmia 11 Answer: E. Sinus arrhythmia The child has sinus arrhythmia, which is particularly impressive in this ECG. Sinus arrhythmia is an exaggerated but normal variation of the sinus rhythm that occurs with respiration. On examination, this may be prominent enough to manifest as an irregular pulse. Sinus arrhythmia is almost universal in the pediatric population, but it may not be as dramatic as the example shown. No further testing is needed on the basis of this ECG, but depending on the quality of the probably innocent flow murmur, echocardiography may be warranted.[3] 12 A 16-year-old male is being evaluated in the ED for a syncopal episode. As part of the workup, a 12-lead ECG is obtained (shown). He is an athlete, but the syncopal episode occurred while standing at home. He has not been feeling well over the past 24-48 hours, with worsening fever, headaches, myalgia, and arthralgia. He is experiencing chest pain but is unsure whether it differs from the aches and pains he has felt all over his body during this time. What is the most appropriate interpretation? A. Normal variant pediatric ECG B. Sinus tachycardia C. Pericarditis D. Sinus rhythm with left ventricular hypertrophy E. Acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction 13 Answer: A. Normal variant pediatric ECG The ST-segment elevations seen in the precordial leads are benign early repolarization with elevated J points (purple arrows), which are normal variants in the pediatric population. The morphology of the segments is concave (curving upward) and thus reassuring. Convex segments (curving downward) are more concerning for acute myocardial infarction. The diffuse STsegment elevations typical of pericarditis are not present in this ECG; PR-segment depressions are also absent. Although the lateral leads have elevated R-wave voltages, this finding is quite common in young, thin athletes and carries no adverse prognosis.[3] 14 A 16-year-old male athlete is being seen for a physical examination before sports participation. The patient’s ECG is shown. A focused history reveals that the patient has had palpitations in the past and an episode of near-syncope, which he thought was due to overexerting himself. As a result, he never went to the physician for it and has never had a workup. In the event of acute supraventricular tachycardia, all of the following medications should be avoided except: A. Digoxin B. Procainamide C. Adenosine D. Metoprolol E. Verapamil 15 Answer: B. Procainamide The patient has Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome (pre-excitation), as evidenced by the characteristic delta waves, the shortened PR interval, and the widened QRS complex (better appreciated in the limb leads). During atrial arrhythmias, drugs that block the AV node may augment conduction down the accessory pathway, which lacks the normal decremental conduction of the AV node. In atrial fibrillation or flutter, 1:1 conduction of atrial rates may precipitate fatal ventricular fibrillation. In stable supraventricular tachycardia, adenosine may precipitate atrial fibrillation and is best avoided. Of the drugs listed, procainamide has the least action on the AV node; however, if procainamide is not readily available and the patient’s hemodynamic stability is in question, amiodarone is a reasonable alternative.[3,8] 16 A 15-year-old Asian male is brought in by paramedics after experiencing a seizure during gym class. His 12-lead ECG is shown. The child has no history of seizure disorder, and he states that he had palpitations before the seizure. The paramedics report that their 12-lead ECG in the field was abnormal because their machine was reading it as acute myocardial infarction, but they were unable to identify typical ST-segment elevations. This ECG is consistent with which of the following abnormalities? A. WPW syndrome B. Brugada syndrome C. Ebstein anomaly D. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy E. Yamaguchi syndrome 17 Answer: B. Brugada syndrome This ECG shows characteristic changes of Brugada syndrome, a sodium channelopathy associated with the gene SCN5A (also implicated in long QT syndrome) that is more prevalent in Asia. The ECG shows 1 of 2 ST-segment morphologies in V1-V3. The “coved” QRS (shown) consists of a right bundle branch block morphology with a slowly downsloping ST segment (red arrow) and an inverted T wave (blue arrow). The ST segment may also take a saddleback appearance in these leads with an upright T wave. Only automatic implantable cardiac defibrillators have been shown to prevent death from arrhythmias in patients with Brugada syndrome. Urgent cardiologic evaluation should be arranged.[9] 18 A 15-year-old female is brought to the emergency department after an episode of syncope during a long-distance running event. Her ECG obtained in the ED is shown. She has no previous ECGs for comparison. She has no prior episodes of syncope, and she is on no medications. The family reports that the child is adopted and her family history is unknown. Until additional cardiac and genetic tests are performed, the child may be at the risk for a cardiac event from: A. Loud noises B. Exercise C. Sleep D. Swimming E. All of the above 19 Answer: E. All of the above The teenager has long QT syndrome, which results from several different ion channelopathies involving cardiac sodium and potassium channels. Depending on the exact genetic abnormality and ion channel involved, many triggers have been identified. The QTc interval in this ECG is approximately 600 ms, which is well above the upper limit of normal for an adult female of 460 ms (440 ms for a male). The 98th percentile for QTc intervals of females of this age is 457 ms. The markedly increased QT interval is also apparent when it is compared with the R-R interval (shown); typically, QT intervals greater than one half of the R-R interval are considered to be prolonged. Immediate referral for cardiologic evaluation is important.[3,10] 20 A 16-year-old female is referred to a pediatric cardiologist for evaluation after episodes of exertional dyspnea and cyanosis. Her initial ECG is shown. Upon questioning, the mother reports a normal birth history but states that the child was very colicky and fed poorly. She remembers having to feed frequently for short periods for much of the first year of life. The patient has been otherwise developing well since then. What is the most likely diagnosis? A. Bicuspid aortic valve B. Left bundle branch block C. Ebstein anomaly D. Exercise-induced asthma E. Long QT syndrome 21 Answer: C. Ebstein anomaly This scenario is consistent with Ebstein anomaly, a congenital abnormality resulting in enlargement and malformation of the tricuspid valve. Valve leaflets are displaced towards the apex of the heart, and part of the right ventricle may become atrialized. The ECG shows marked right-axis deviation with giant P waves (blue arrows) due to the enlarged right atrium. An rSr' complex in V1 (red arrow) is consistent with a right ventricular conduction delay. Although Ebstein anomaly is often diagnosed in childhood, many patients remain asymptomatic until adulthood. Heart failure and arrhythmias are the main concerns for these patients, who ultimately may require surgical intervention. Regular cardiologic follow-up is critical to good care.[3,11] 22 A 17-year-old male is brought in by advanced life support after acute onset of palpitations. He denies having chest pain or shortness of breath but is anxious and very uncomfortable. He had no known cardiac history, and this has never happened before. His blood pressure is 106/48 mm Hg and stable. Amiodarone injection and rapid intravenous push of adenosine have not terminated the rhythm. What is the next appropriate step in management? A. Synchronized cardioversion B. Intravenous diltiazem C. Intravenous metoprolol D. Immediate defibrillation E. Intravenous verapamil 23 Answer: E. Intravenous verapamil This patient has an acute episode of verapamil-sensitive idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia, which is a class of recurrent, monomorphic ventricular tachycardias that occurs in young males who have no gross structural abnormalities of the heart. The cause is typically a reentrant circuit in the ventricular septum, particularly the left posterior fascicle. It is characterized by left-axis deviation or, in some cases (such as this patient), extreme right-axis deviation as shown in leads I and aVF. A characteristic right bundle branch block morphology is also present. Termination of an acute episode is accomplished with verapamil, but long-term therapy often requires ablation of the reentrant circuit. Long-term prognosis is generally benign.[12,13] 24 Related Slideshows Are You Missing an MI? Can't-Miss ECG Findings, Life-Threatening Conditions Subtle EKG Syndromes in Children and Adults Six Abnormal ECGs — Not All Are Cases of the Heart Other Slideshows For More Information Medscape Reference: Brugada Syndrome Medscape Reference: Ebstein Anomaly Medscape Reference: First-Degree Atrioventricular Block Medscape Reference: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Medscape Reference: Junctional Rhythm Medscape Reference: Long QT Syndrome For More Information 25 Medscape Reference: Pediatric Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Medscape Reference: Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome Medscape Today: Electrocardiographic Manifestations: Pediatric ECG ECG Wave Maven Contributor Information Authors Michael S. Westrol, MD House Staff Department of Emergency Medicine UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School New Brunswick, New Jersey Disclosure: Michael S. Westrol, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Raffi Kapitanyan, MD Assistant Professor Department of Emergency Medicine UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School New Brunswick, New Jersey Disclosure: Raffi Kapitanyan, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Contributor Information Editor Lars Grimm, MD, MHS House Staff Department of Diagnostic Radiology Duke University Medical Center Durham, North Carolina Disclosure: Lars Grimm, MD, MHS, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Reviewer Alan R. Morrison, MD/PhD Cardiology Fellow Yale-New Haven Hospital New Haven, Connecticut 26 Disclosure: Alan R. Morrison, MD/PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Although most physicians are familiar with the normal limits of ECG intervals for adults, it may not be immediately apparent that children have different normal values. Population studies have helped to formulate generally accepted normal values for children at various ages,[1] which should be referenced when interpreting an ECG. However, even with these values, it may be difficult to make a diagnosis. Variation occurs in children depending on age and sex, but most pathologic conditions fall well outside the range of normal. See whether you can determine whether the ECGs in the following cases are benign variants from the norm or cause for concern. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.