Critical Reading Response: Machiavelli, “Qualities of a Prince” 1

advertisement

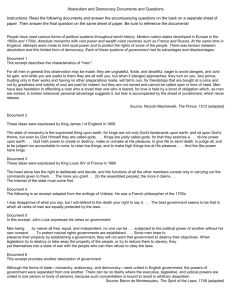

Critical Reading Response: Machiavelli, “Qualities of a Prince” 1. Context. a. Biographical Context. Who wrote the text? What other major texts did he/she write? Why is he/she noteworthy? In other words, why should we consider the author an expert or authority on the subject about which he/she writes? Machiavelli is known today primarily as a political philosopher. Born into a prominent family in Florence, he served in a number of political, judicial, and military positions between the 1490s and 1512, when the Medici seized power in Florence once again. Briefly imprisoned and tortured by the Medici regime, Machiavelli retired and wrote plays and political tracts upon his release from prison. His most notable work is The Prince, first published in a limited run in 1513. It was later published more widely in 1532. b. Social and Historical Context. Identify the historical and social context of the text. When was the text written? What were the significant issues of the day? With whom (or what idea) is the text engaged in a critical conversation? In other words, few texts are created in a vacuum; they usually engage other texts and conditions in a sort of ongoing “conversation” or debate. You must identify the rough parameters of this debate. The late 15th- and early 16th-century in Italy was an era of great political and military instability marked by wildly shifting temporary alliances. The major powers included the Italian city-states (Venice, Florence, etc.), the Holy Roman Empire, France, and Spain. The papacy was incredibly powerful and, in many respects, ruthless in its pursuit of economic and military power. The Italian city-states were ruled in large part by prominent families like the Medici family. Its political power based largely upon its large banking empire, the Medici family had ruled Florence from the late 14th century but lost its hold over the republic between 1490 and 1512. It re-seized power in 1512. Machiavelli wrote The Prince against this backdrop of political intrigue, offering advice to “princes” on how to gain, sustain, and/or expand their political, military, and economic power. 2. Summary. In one paragraph (5-8 sentences), summarize the text. For longer texts, of course, you will likely have to add additional paragraphs. A book-length text, for example, might require a paragraph per chapter. Machiavelli ostensibly conceived The Prince as a primer for contemporary leaders, both aristocratic and republican. Written as a political philosophy tract in the “Mirror of Princes” tradition, the controversial text runs counter to more traditional classical and Catholic writings on the subject of statecraft and leadership. The excerpt in our text, “Qualities of a Prince,” privileges pragmatism over idealism as it argues from the baseline position that man is, by nature, corrupt; no man is completely virtuous. As such, men – whether political leaders or members of the general populace – tend to act in their own self-interest. Focusing upon this idea of pragmatic self-interest, Machiavelli identifies a number of specific traits a prince should have. He notes, however, that not all of the virtues are equal and, just as important, that it is practically impossible for one person to exercise all of them simultaneously. Thus, he concludes, princes should focus solely on those virtues that solidify their power. Moreover, as he privileges appearances over reality, Machiavelli insists that leaders should merely appear to have a virtue while actually practicing a more realistic brand of leadership that runs directly counter to that virtue. In other words, a leader should appear merciful but be stern, appear religious but be pragmatic, and appear peaceful while always actively pursuing military preparations. In fact, Machiavelli argues that so-called “positive” values often lead to unforeseen negative consequences. A prince who is generous will give away too much capital while only making his subjects lazy and greedy. His generosity thus leads to lavish lifestyles which, in turn, require the prince to increase taxes or be continuously at war to gain new sources of revenue. This situation is, in the long run, untenable. Therefore, he concludes, princes should be miserly. And because princes must routinely act in accordance with such “negative” values, they must remain ever aware of the fine line between fear and hatred. Fear, Machiavelli suggests, yields positive results while hatred breeds contempt and poses a significant threat to the prince’s stability. 3. Analysis. a. Thesis. Identify the thesis. (Again, for longer texts, you will likely have to break down the text into chapter-length sections and identify each section’s thesis, as well.) Though there are a number of “possible” thesis statements, the following excerpt best captures Machiavelli’s thesis. “…[I]t is necessary for a prince who wishes to maintain his position to learn how not to be good, and to use this knowledge or not to use it according to necessity” (42). b. Claims. Identify the major subordinate claims that support the thesis. Princes must remain focused on military operations – either in training, active preparation, or the conduct of combat operations (39-42). Like Hegel, Machiavelli seems to contend the “history of the world is but the biographies of great men.” Thus, princes must read histories and biographies of the great leaders of history for examples on how to lead/live (41). Those virtues which, at first glance, might seem beneficial for a leader (generosity, mercy, benevolence, veracity, etc.) might actually be counterproductive. Conversely, perceived negative attributes, which he calls “vices” (cruelty, miserliness, lying, etc.) are often necessary to sustain one’s power (44). Argues that it is often better to be feared than loved (46). Appearances are infinitely more important than reality. (49). c. Notable Passages. Identify at least three interesting, important, or striking phrase- or sentence-length passages. Write a paragraph (5-8 sentences) in which you summarize and then assess each selected passage. “A prince…must not have any other object nor any other thought, nor must he take anything as his profession but war, its institutions, and its discipline; because that is the only profession which befits one who commands” (39-40). “…never in peaceful times must he [the prince] be idle…” (41). It would seem “more suitable…to search after the effectual truth of the matter rather than its imagined one” (42). Miserliness is “one of those vices that permits…[a prince] to rule” (44). “…spending the wealth of others does not lessen your reputation but adds to it; only the spending of your own is what harms you” (44). “For one can generally say this about men: that they are ungrateful, fickle, simulators and deceivers, avoiders of danger, greedy for gain, and while you work for their good they are completely yours, offering you their blood, their property, their lives, and their sons, …when danger is far away; but when it comes nearer to you they turn away” (46). “……there are two means of fighting: one according to the laws, the other with force; the first way is proper to man, the second to beasts; but because the first, in many cases, is not sufficient, it becomes necessary to have recourse to the second” (48). “…a prince must know how to use wisely the natures of the beast and the man” (48). “But it is necessary to know how…to be a great hypocrite and a liar: and men are so simpleminded and so controlled by their present necessities that one who deceives will always find another who will allow himself to be deceived” (48). “…it is necessary that he have a mind ready to turn itself according to the way the winds of Fortune and the changeability of affairs require him; and…as long as it is possible, he should not stray from the good, but he should know how to enter into evil when necessity commands” (49). “Everyone sees what you seem to be, few perceive what you are” (49). d. Key words. Identify between three and five critical words or terms from the text. These terms may or may not recur throughout the text but nevertheless seem significant to the author and his/her claims. If you do not understand the term, define it within the context of its use. Write a sentence about each term’s significance to the text. Fear/Hatred – Though he must walk the fine line between inspiring fear and hatred in his subordinates, the prince must not, according to Machiavelli, “worry about being considered cruel” (46). Manipulate – Leaders “who have accomplished great deeds,” Machiavelli insists, know “how to manipulate the minds of men by shrewdness” (48). Necessary – Exigency, Machiavelli argues, requires the prince to lead by whatever means necessary. Though he ought, when possible, to rule with “all mercy, all faithfulness, all integrity, all kindness, [and] all religion,” he must also know when to “enter into evil when necessity commands” (49). 4. Structure. Number each paragraph. Divide the text into component parts. Identify which paragraphs comprise the section. Assign a representative title to each section. For book length texts, identify which chapters comprise specific sections. I. II. III. IV. Prince as Commander: The Exigency of Military Art (1-6). Appearances vs. Reality or Pragmatism and the Prince (7-11). Fear and Loathing in the Realm of the Prince (12-18). Hypocrisy and the Incredible Lightness of Seeming Versus Being (19-28). 5. Rhetorical Strategies. Identify the text’s dominant and supporting rhetorical strategies / patterns of development. Briefly explain each. Though the excerpt shows evidence of all of the rhetorical strategies, Machiavelli appears to privilege the exemplification and process patterns of development while relying heavily upon the definition and compare and contrast strategies, as well. He details, for example the process of preparing for combat in times of war (40). He gives numerous examples from history in support of his claims throughout the chapter: Philopoemon (41), Cyrus (41), Julius II (44), Louis XII (44), Ferdinand V (44), Cesare Borgia (45), Hannibal (46), Nabis the Spartan (50), Giovanni Bentivoglio (51). He compares the armed man vs. the unarmed man (40). He contrasts values like “purity, goodness, humanity, and generosity” with their opposing “evils” (41-45). 6. Marginalia. Transfer your marginalia in bullet form. Place the paragraph or page number in parenthesis after each note so you can refer back to the text for context if necessary. 37: Pragmatism vs. idealism Practicality necessarily opposes morality? Tyranny Ends justify means? Cynicism. Is vs. should be situation you will often find yourself in for the rest of your life. Appearances vs. reality. List of contrasting qualities p. 42 38: Remember, this is a translation! Significant Words: command, wise prince How can we translate don’t steal a man’s woman or property into contemporary warnings that apply to leaders? p. 50. 40: Combat: how to keep power or gain it. Action vs. contemplation/thought Value of hardship 41: Suspicion and contempt of the unarmed breeds instability and mistrust. Values the deliberative as well as the active leader – Philopoemon as example. Value of imitative leadership. 42: Imaginary vs. real not, though, in a Platonic lens Never seems to give moderation a thought as seen in list of dichotomies until the very end of the section rhetorical strategy? Explore. List of vices Reality vs. ideal. Learn it – not necessarily do it (“how not to be good”) Generous vs. miserly; giver vs. rapacious; cruel/malicious vs. merciful; treacherous vs. faithful. 43: Argument for measured generosity? NO! benevolent miserliness…? 48: The fox and the lion. 52: Cynicism/cynical Unscrupulous Value skills in war True but defn. of war has expanded Ends justify means? Ends justify terror or tyranny?