s-s-vs-s-r

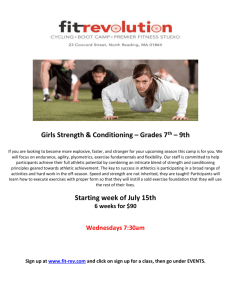

advertisement

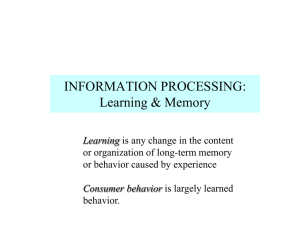

Psychology 514 Handout on S - S* vs S - R theoretical views of conditioning: What is learned? A longstanding theoretical question in the conditioning literature is whether conditioning is S - S* or S - R in nature. Historically, this question involves asking what is learned. Suppose we conduct ordinary first-order conditioning trials in which an originally neutral CS is associated with a US. We find that the CS now elicits a response that it formerly did not. What is the most accurate way to talk about the learning that has taken place? Have we produced some sort of connection between the CS and the US? In other words, has the subject learned that a particular US follows the CS? If so, then it is appropriate to describe the conditioning as S - S* in nature. Alternatively, have we produced some sort of connection between stimulus and response? In other words, has the subject learned via temporal contiguity to make a particular response to the CS? If so, then it is appropriate to describe the conditioning as S - R in nature. Thus, this question as phrased above concerns the theoretical basis or interpretation for ordinary first-order conditioning. It is not concerned with higher-order conditioning or sensory preconditioning. The S - S view is also called the stimulus substitution view, meaning that the CS comes (a) to act as a substitute stimulus for the US, and (b) to elicit a CR that is the same (or at least very similar; slightly decreased magnitude is OK) to the UR. Some researchers also call the S - S view the expectancy view, in the sense that through conditioning the subject comes to expect a particular US after the CS. How to test these interpretations experimentally? First we conduct ordinary first-order CS-US training. Then we change the conditioning value of the US and the response it elicits independently of the CS. Then we present the CS in test trials and measure the response it elicits: Different from original training (i.e., reflecting the new value we have imparted to the US) or same as (i.e., reflecting the original training value of the US) ? The general term for manipulations of this sort that involve the US is “revaluation.” One way to revalue a US is through habituation, as in Rescorla (1973). The specific revaluation in Rescorla (1973) is called devaluation, as it involves decreasing the conditioning value of the US and decreasing the response it elicits. Note that we could also increase (inflate) the magnitude of the US and the response it elicits. If the CS elicits a different CR after the revaluation, we conclude S - S*. The CS is eliciting a response based on the value of the US at the time of testing, which after revaluation differs from its original value, but which nevertheless reflects an S - S* rather than S - R relation. If the CS elicits the same CR after revaluation, we conclude S - R. The CS is eliciting a response based on the temporal contiguity between the CS and the response elicited by the US during original training. The revaluation of the US hasn’t modified this relation because the revaluation was carried out independently of the temporal contiguity between the CS and any response in its presence.