Gastroparesis - "Delayed Stomach Emptying"

advertisement

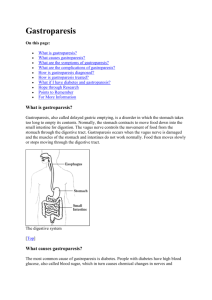

Gastroparesis - "Delayed Stomach Emptying" By gi health How your stomach works Most people don't know that the stomach lies high in the left upper abdomen protected by the lower rib cage. Empty, the volume of the stomach "pouch" is less than one-half cup. As you eat, the stomach's muscular wall can relax and expand to hold about three pints of sustenance. The stomach's job is to liquify solid food preparing it for digestion and absorption in the small intestine. This is done by mixing the food with powerful digestive juices for several hours. To hold the food within the stomach there are two valves. At the top of the stomach is the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) which prevents backsplash of stomach contents upward into the esophagus. At the bottom of the stomach is the pylorus which controls the "drain" of the stomach. Once these two valves are closed, muscular contractions called peristaltic waves ripple through the stomach squeezing gently in the upper part (fundus), more powerfully lower down (antrum). These contractions are controlled by a stomach pacemaker, much like the heart, and travel through the fibers of the vagus nerve. When the pacemaker fires, this muscular churning motion mixes the food particles with powerful hydrochloric acid and the enzyme, pepsin. Produced by the stomach, these strong chemicals convert the food to about the consistency of cream of potato soup. Eventually the pylorus relaxes slightly, opening the stomach's drain. The stomach muscle contracts and the now liquefied food is pumped a little bit at a time through the valve and into the small intestine where the digestive process occurs. Pump failure When all is working, the fullness we feel after eating a big meal gradually fades as the stomach empties its contents into the small intestine. After a few hours, the stomach is completely empty and ready for the next meal. What if the stomach pacemaker would slow or the pump fail? Then the stomach would drain much more slowly and not empty completely between meals. With the next meal, you would feel bloated and perhaps nauseated. There would be no room for more food and vomiting of undigested food might occur. Each meal would be an ordeal. You might be afraid to eat and begin to lose some weight. This is what patients with gastroparesis have to put up with each day. What is gastroparesis? Gastroparesis (gastric = stomach; paresis = paralysis) literally means stomach paralysis. It is a condition in which the stomach muscle becomes slow and weakened. Following a meal, it takes too long for the stomach to empty its contents into the small intestine. What are the symptoms? One problem in identifying gastroparesis is the fact that the symptoms are often vague. Most symptoms occur because the stomach doesn't empty completely. Some residual food is always present. This may cause excessive fullness after meals, frequent burping, acidreflux, nausea, and abdominal distention. Vomiting of undigested food often occurs 1 to 3 hours after meals. Individuals often complain of early satiety - feeling full before the meal is finished. Eventually, fear of eating may lead to unplanned weight loss. Persistent vomiting can cause low blood potassium, dehydration, and malnutrition. Diabetics may have complications because of poor blood sugar control. What causes gastroparesis? The cause is not known, but gastroparesis is a common complication of Type 1 insulindependent diabetes occuring in about 20% of patients - especially in those who have developed other signs of nerve damage (diabetic neuropathy) such as numbness or burning of the feet. People with Type 2 diabetes get it also, but less often. Diabetic gastroparesis can be a vicious cycle since diabetes causes nerve damage which leads to gastroparesis. And gastroparesis can worsen diabetic control since delayed stomach emptying makes digestion unpredictable which results in uneven blood sugar levels. Gastroparesis may also be a complication of stomach surgery for ulcer disease or weight loss. Some systemic disorders such as kidney failure, lupus, Parkinson's disease, sclerodema, and thyroid disorders can also delay gastric emptying. Up to 30% of individuals with gastroparesis are idiopathic, meaning that there is no identifiable cause. It is felt that some of these may be due to an acute viral infection. Lastly, some medications such as anticholinergics (antispasmodics) can worsen the situation. How is gastroparesis diagnosed? Not everybody who is bloated has gastroparesis. In fact, most of the time, bloating and exessive fullness is caused by Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). But, when symptoms are severe, the possibility of gastroparesis must be considered, especially in diabetics. Of course, prior stomach surgery, certain systemic disorders, and offending medications must be ruled out. If gastroparesis is suspected, blood tests are usually done to assess diabetic control and nutritional status. In addition, three imaging studies are available: An Upper GI Series x-ray with barium may be done to obtain some information about the size of the stomach and determine if any retained food is present when fasting. Occasionally, a bezoar is found. This is a large ball of undigested vegetable matter that is trapped inside the stomach. In most cases, a Gastroscopy "scope" test is performed to rule out more serious conditions such as a blockage due to ulcer disease or stomach cancer. The most important test is a radioisotope gastric-emptying scan done at the hospital nuclear medicine department. The patient is given a meal that contains a radioisotope, a slightly radioactive substance that will show up on the scan. The dose of radiation from the radioisotope is small and not dangerous. After eating, the patient is asked to lie under a large geiger counter that detects the radioisotope and shows an image of the food in the stomach and how quickly it leaves the stomach. The test takes 2 to 4 hours. Gastroparesis is diagnosed if more than half of the food remains in the stomach after 2 hours. What is the treatment? As yet, there is no cure for gastroparesis, but in most cases, symptoms can be improved with treatment. Regardless of the cause, treatment programs are fairly similar. Diet Changing how and what foods are eaten is helpful. It is best to eat six small meals a day, instead of three large ones. Liquid dietary supplements are often recommended since liquid meals pass through the stomach more easily and quickly. Avoid high fat foods that naturally slow gastric emptying and foods high in fiber like citrus and broccoli because the indigestible part will remain in the stomach too long. Medications Propulsid (cisapride) was developed to treat this condition and was of benefit to thousands of patients. Unfortunately, it was linked to about 300 cases of heart rhythm irregularity including 80 deaths and was taken off the market in 2000. With the removal of Propulsid, an older drug, Reglan (metoclopramide), has again become the drug of choice. It has been shown to be effective in the acute management of many gastroparetic conditions, but often loses its effectiveness over time. It can be given by mouth, intravenously (into the vein), subcutaneously (under the skin), and rectally. Unfortunately, side effects are common including drowsiness, loss of menstrual periods, impotence, and muscle spasms. With prologed use, some patients develop a Parkinson's-like tremor. Benadryl can limit some of the side effects but worsens the drowsiness. Erythromycin has become the gastric prokinetic of choice for those patients who fail to respond to conventional agents. This antibiotic also acts to stimulate the muscles of the stomach to contract. It can be given intravenously and by mouth. Domperidone (Motilium, Janssen) is another drug that improves gastric emptying and may have less side-effects. It has been available overseas (and even over the counter in Europe), but is not FDA approved in the US. None of these drugs are totally effective and without side effects. Research is ongoing. Two new drugs that may possibly be helpful are Zelmac (tegaserod), a new drug for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with constipation and Viagra (sildenafil), which is marketed for male erectile dysfunction, but has also shown some benefit. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University found that part of the delay in stomach emptying occurs as a result of lack of nitric oxide in stomach tissues. The same basic molecular problem causes impotence in men. Experiments have shown that in mice Viagra reversed gastroparesis. Human trials are underway. When nausea is a predominent symptom, a separate anti-nausea drug is often added such as Compazine (prochlorperazine) or Trans-Scop (scopolamine patches). But, again, side effects are common. In severe cases Zofran (ondansetron) may be used, but is very expensive. In milder cases of nausea, accupressure wrist bands are a non-invasive method that most patients tolerate well. Surgery Surgery is seldom done for gastroparesis, but in severe cases, a feeding jejeunostomy tube can be placed surgically. This thin plastic tube goes through the skin of the abdominal wall and directly enters the small intestine far downstream from the stomach. Special liquid nutrition given through this feeding tube bypasses the mouth, esophagus, and stomach and is delivered directly to the small intestine for absorption. Gastric Pacemaker On April 8, 2000, the FDA approved a stomach pacemaker called Enterra (Medtronic Corporation) for "compassionate use". This electrical device is implanted in the abdomen and functions much the same way a pacemaker works in the heart. Enterra is indicated for the treatment of chronic nausea and vomiting associated with gastroparesis when conventional drug therapies are not effective. You can read more about the pacemaker at Medtronic's website. Summary Gastroparesis is a common condition that may affect anyone, but most often is seen as a complication of insulin-dependent diabetes, especially in those who have other signs of nerve damage like numbness of the feet. Up to a third of cases have no identifiable cause. Gastroparesis causes early fullness, bloating, nausea, vomiting, weight loss and contributes to poor blood glucose control. In severe cases, it can affect nutrition. Treatment is available, but, as yet, there is no cure. Treatments include changes in diet, better control of blood sugar, oral medications, and, in severe cases, a jejunostomy. Research is promising and new treatments may be just beyond the horizon.