FDA Stakeholder Meeting on ME CFS, April 25

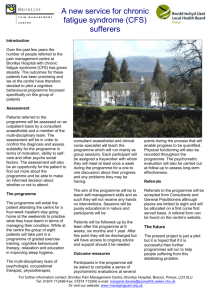

advertisement