Click here

advertisement

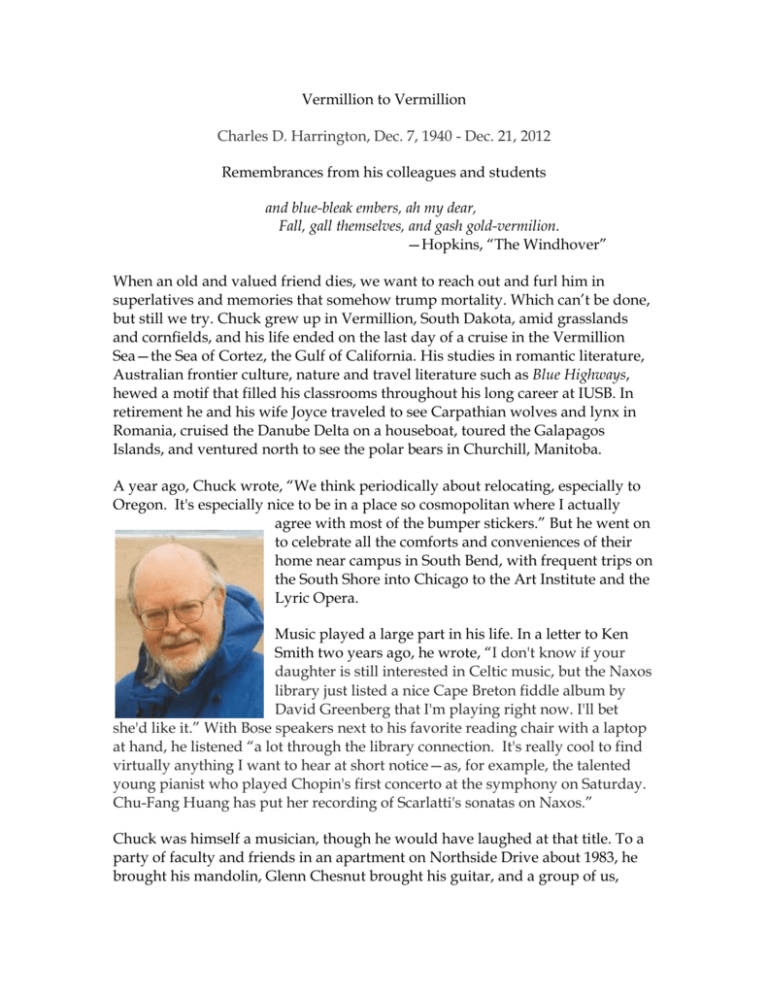

Vermillion to Vermillion Charles D. Harrington, Dec. 7, 1940 - Dec. 21, 2012 Remembrances from his colleagues and students and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear, Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion. —Hopkins, “The Windhover” When an old and valued friend dies, we want to reach out and furl him in superlatives and memories that somehow trump mortality. Which can’t be done, but still we try. Chuck grew up in Vermillion, South Dakota, amid grasslands and cornfields, and his life ended on the last day of a cruise in the Vermillion Sea—the Sea of Cortez, the Gulf of California. His studies in romantic literature, Australian frontier culture, nature and travel literature such as Blue Highways, hewed a motif that filled his classrooms throughout his long career at IUSB. In retirement he and his wife Joyce traveled to see Carpathian wolves and lynx in Romania, cruised the Danube Delta on a houseboat, toured the Galapagos Islands, and ventured north to see the polar bears in Churchill, Manitoba. A year ago, Chuck wrote, “We think periodically about relocating, especially to Oregon. It's especially nice to be in a place so cosmopolitan where I actually agree with most of the bumper stickers.” But he went on to celebrate all the comforts and conveniences of their home near campus in South Bend, with frequent trips on the South Shore into Chicago to the Art Institute and the Lyric Opera. Music played a large part in his life. In a letter to Ken Smith two years ago, he wrote, “I don't know if your daughter is still interested in Celtic music, but the Naxos library just listed a nice Cape Breton fiddle album by David Greenberg that I'm playing right now. I'll bet she'd like it.” With Bose speakers next to his favorite reading chair with a laptop at hand, he listened “a lot through the library connection. It's really cool to find virtually anything I want to hear at short notice—as, for example, the talented young pianist who played Chopin's first concerto at the symphony on Saturday. Chu-Fang Huang has put her recording of Scarlatti's sonatas on Naxos.” Chuck was himself a musician, though he would have laughed at that title. To a party of faculty and friends in an apartment on Northside Drive about 1983, he brought his mandolin, Glenn Chesnut brought his guitar, and a group of us, fugitives from the undergraduate 60s, performed a professorial hootenanny. Someone might have played a banjo. Or should have. Chuck had a fine, measured prose style and a patient, amused presence at departmental meetings. He managed to stay above academic politics, that most paltry exercise of power. Ken Smith remembers, “After an administrator announced that pigs would fly before a certain kind of benefit would return to the English department, Chuck boosted our morale by bringing a battery-operated winged pig to our monthly meeting. He affixed the little creature by fishing line to the ceiling and we applauded as it flew a tight circle above us. The emblem of the flying pig remains the department mascot and appears on the annual calendar.” When his country prepared too casually for war some years ago, and many folks gathered on campus to read famous poems about war, he arrived with a surprising, little-known, well-aimed passage from Byron that he read beautifully and movingly. He found music in those lines as surely as he did when he whistled lyrically on his way through the corridor at the end of a day of teaching. He was our Mr. Chips, riding his basic, black English bicycle to and from campus, his briefcase fastened to the rear carrier, and in cool weather, wearing his black beret. He was a beloved man in an authentic mustache, who once asked ironically of some movie destined for a worst-ten-movies list, “But does it have a redeeming prurient interest?” His students remember him with great love, and a good number of them conspired to throw a surprise party for him on his retirement. Thomas Hoffman writes, “Dr. Harrington was a very learned scholar who could teach simply by being the kind soul that he was. I don't recall him ever having to resort to gimmicks to get a class's attention. Students who cared were kind and respectful and those who wanted to learn wrote down what he had to say. . . . He came to watch me teach at Howe Military School, an hour away from where he lived. Although I was petrified, I was sincerely happy he showed up and then expounded on my lesson for the kids in class. Truly, he was the leader of the band.” Years after being a student in Chuck’s classes, Phyllis Moore-Whitsell, then a lecturer in English, recalls: I sat beside him in a department meeting one day and listened while he read something he had written to share with colleagues. By that time, having read and responded to so much freshman writing, I had become starved for the beauty of language. As Chuck read his prose, my heart picked up a beat, and when he had finished, all I could say was, "Your writing is beautiful." Ever controlled, as he was, in his life and in the classroom, his writing was an extension of who he was, a man who whistled out a life well lived. Chuck Harrington led us by example, never conspicuous, never posturing or gesticulating, never insisting himself, but always there in the truest way, for his family, his colleagues, and his students—a caring, intelligent sensibility.