CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION TO MORPHOLOGY

advertisement

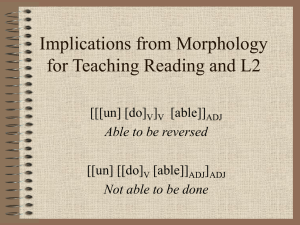

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION TO MORPHOLOGY AND LANGUAGE CHANGE • Morphology is concerned with the internal structure of words and the rules for forming words from their subparts, which are called morphemes. • Morphemes are the smallest units in the structural analysis of words. [[[ green ] ish ] ness] [un [break [able]]]It is often said that morphemes are the smallest units of meaning, butthis is not quite accurate. They are the smallest structural units thelearner identifies; to be identified as such a morpheme must have anidentifiable grammatical behavior, but not necessarily an identifiable meaning. [ trans [ mit ]] [ trans [ miss ]] ion] [ per [ mit ]] [ per [ miss ]] ion] • Although we know that the subparts of these words once had constant meanings (L trāns ‘across, per ‘through’, cum ‘with’, mitt-ere ‘to send’) the learner of contemporary English does not know this (ordinarily). • In any case the words don’t mean ‘send across, send, through, send with’ • However, the root [mit] shows an identifiable contanst grammatical behavior: it changes to [miss] when the verb is used to make the corresponding noun through suffixation of [-ion] 2 Open and Closed Class Items • Morphemes are divided into two types: open class and closed class • Open class items belong to categories/types to which new members may be freely added • For example, you certainly don’t know all the ‘nouns’ in English, and even if you did, new words come into use all the time to refer to things recently created, discovered or named: quark, google, blog, tweet, grunge • Closed class items on the other hand belong to categories/types to which new members cannot be added • For example, plural agreement in English is normally expressed with [-s], as is 3rd person singular present tense agreement. • The agreement morphemes are a closed class: new agreement morphemes cannot be added to an adult’s grammar. • Similarly the modal verbs do, did, have, be, may, might, shall, should, will, would, can, could, ought form a closed class in English. These are the only verbs which can precede negation not or n’t in Modern English: I did not see the movie. *I saw not the movie (archaic) I (should) think not! (‘frozen’ expression: cannot be altered) Closed class items are often called ‘functional’ items because they typically have a grammatical function such as showing agreement, or marking or changing the category of other items to which they attach. [[quark] s] [[google] ed] [[tweet] ing] [[grunge] y ] ness] Inversely, open class items are sometimes called lexical because they form part of a vocabulary that must be memorized. (This use of lexicon to mean open-class vocabulary differs from some otheruses of the term, however!) Recent work in sociolinguistics has raised once again a long-standing question: can linguistic change be observed while it is actually occuring? In modern linguistics the answer to that question has usually been a resounding negative. Following the example of two of the founders of the modern discipline, Saussure (1959) and Bloomfield (1933), most linguist have maintained that change itself cannot be observed; all that you can possibly hope to observe are the consequences of change. The important consequences are those that make some kind of difference to the structure of a language. At any particular time, it certainly may be possible for linguists to observe variation in language, but that variation is of little importance. As indicated earlier, such variation was to be ascribed either to dialect mixture, that is, to a situation in which two or more system have a degree of overlap, or to free variation, that is, to unprincipled or random variation. Only in recent years have some of them seen in it a possible key to understanding not only how languages are distributed in society, but also how that distribution may help us to understand how change occurs in language. CHAPTER II A. Definision Morphology Morphology according to wikipedia is identification , analysis and description of the structure of morphemes and other units of meaning in the language like words, affixes, and part of speech and intonation/stress, implied context ( word in lexicon are the subject metter of lexicology). Morpholgy according to Dr. C. George Boeree is Morphology is the study of morphemes, obviously. Morphemes are words, word stems, and affixes, basically the unit of language one up from phonemes. Although they are often understood as units of meaning, they are usually considered a part of a language's syntax or grammar. It is specifically grammatical morphemes that this chapter will focus on. Morphology according to Hadi Rukkiyah is Morphology or morphemic means learning how to form words (word-organization). It is a branch of linguistics which deals with the organization of phonemes into meaningful groups called morphs. A morph is the smallest meaningful part of language. B. Definision of Language Change Language Change according to wikipedia is Languages change, usually very slowly, sometimes very rapidly. There are many reasons a language might change. One obvious reason is interaction with other languages. Language Change according to William Caxton is (ca. 1415~1422 – ca. March 1492) was an English merchant, diplomat, writer and printer. As far as is known, he was the first English person to work as a printer and the first to introduce a printing press into England. He was also the first English retailer of printed books (his London contemporaries in the same trade were all Dutch, German or French). CHAPTER III CONTENT In many language, what appear to be single form actually turn out contain a large number of ‘word-like’ elements. For example, in swahili ( spoken throughout East Africa), the form nitacupenda conveys what, in English, would have to be represented as something like i will love you. Now, is the swahili form a single word? If it is a ‘word’ then it seems to consist of a number elements which ,in English. Turn up a separate ‘wod’. A very rough correspondence can be presented in the following way: Ni –ta I will –ku -penda you love It seems as if the swahili ‘word’ is rather different from what we think of as an English ‘word’’ Yet, there clearly is some similarity between the languages, in that similar elements of the whole message can befound in both. Perhaps a better way of looking at linguistic forms in different languages would be to use this notion of elements in the message, rather than to dipend on identifying ‘word’. The type of exercise we have just performed is an example of investigating forms in language generally known as morphology. This term, which literally means ‘the study of form’, was originally used in biology, but, since, the mid nineteenth century, has also been used to describe that type of investigation which analyzes all those basic ‘elements’ which are used in a language. Morphology in the tme thechild 3 years old, he or she going beyound telegraphic speech forms and incorporating some of the inflectional morphemes with grammatical function of the noun and verb. The first to appears is the usually the –ing form. For example cat sitting and mommy reading book. Then comes to marking of plural with the –s as boys and cats. When the alternative pronunciation of the plural morphemused in house ( i.e ending |-ez|) comes into use. It too is given on overgeneralized application and form such as boyses or footses can appear. At the some time as this overgeneraization is taking place. It also begin using irregular plurals such as men quite appropriately for a while, but then try out the general rule on the forms producing expressions like some mens and two feets/ even two feetses. The use possesive inflections –‘s occurs in expressions such as girls and mummy’s book and the different forms of the verb ‘to be’, such as are and was, turn up . The appearanceof forms such as was and, at about the same time, went and came should be noted. These are irregular past tense forms which one would not expect to appear before the more regular forms. However, they do typically precede the appearance of the –ed inflection. Once the regular past tense forms begin appearing in the child’s speech ( e.g. walked, played ), then, interestingly, the irregular forms disappear for a white and are replaced by over generalized versions such as goed and comed. For a period, there is often minor chaos as the – ed inflection is added to everything , producing such oddities as walkeded and wanted. As with the plural forms, however the child works out, finally , the regular –s marker on third person singular present tense verb appears it occurs intially with full verbs (comes, looks ) and then with auxiliaries (does, has ) Throughout this sequence there is, of course, a great deal of variability, individual children may produce ‘good’ forms comes day and ‘odd’ forms the next. It is important to remember that hte child is working out how to use linguistic system while actually using it as a means of communication. For the child, the use of forms such as goed and foots is simply a means of trying to say what he or she means during particular stage of development. The embrassed present who insist that the child didn’t hear such things at home are implicitly recognizing that ‘ imitation’ is not the primary force in child language acquisition. C. Language Change Languages change, usually very slowly, sometimes very rapidly. There are many reasons a language might change. One obvious reason is interaction with other languages. If one tribe of people trades with another, they will pick up specific words and phrases for trade objects, for example. If a small but powerful tribe subdues a larger one, we find that the language of the elite often shows the influence of constant interaction with the majority, while the majority language imports vocabulary and speaking styles from the elite language. Often one or the other simply disappears, leaving behind a profoundly altered "victor." English is, in fact, an example of this: The Norman French of the conquerers has long disappeared, but not before changing Anglo-Saxon into, well, a highly Frenchified English. The historical development of English is usually divided into three major periods. The old English period is considered to iast from the time of the earliest written records,the seventh century, to the end of the eleventh century. The Middle English period is from 1100 to 1500 and Modern English from 1500 to the present. Example of a very influential people: Around 5000 bc, between the Danube river valley and the steppes of what is now the Ukraine, there lived small tribes of primitive farmers who all spoke the same language. They cultivated rye and oats, and kept pigs, geese, and cows. They would soon become the first people on earth to tame the local wild horses -- an accomplishment that would make them a significant part of history for thousands of years to come. By examining the oldest examples of modern and classical languages such as Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit, linguists have been able to reconstruct an educated guess as to what the language of these ancient people was like. They call the language Proto-Indo-European. The work that went into reconstructing Proto-Indo-European has led to efforts to reconstruct other prehistorical language ancestors as well. Latin Italian Spanish Portuguese French Latin Italia Spanyol Portugis dicto detto dicho dicto detto Dicho dito Dito Prancis dit dit English Bahasa Inggris said kata lacte latte leche lacte latte Leche lecto letto lecho lecto letto lecho nocte notte noche nocte notte noche leite Leite lait lait leito leito noite noite lit milk susu bed menyala tidur nuit night Nuit malam So one "rule" could be that a "difficult" combination of letters like -ct- change in certain ways to end up "simpler." In most of the descendent languages, it just became -t-; in Spanish, it became ch. Another example: Words that began with pl-, cl-, or flin Latin changed in a systematic way as well. In this case the initial consonant combinations "simplified" in different ways in Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese, but remained the same in French. In Italian, the l became an i, in Spanish they became ll (pronounced like y), and in Portuguese they became ch (pronounced like sh): Latin Italian Spanish Portuguese French English Pleno pieno Lleno Cheio Plein Full Clave chiave Llave Chave Clef Key Flamma fiamma Llama Chama flamme Flame Over time, the linguists learned the patterns of change, and have used them to reconstruct languages whose original versions we no longer have any record of -such as Proto-Indo-European! They are able to use some of the oldest versions of the different branches of the Indo-European languages as a foundation: English Sanskrit Greek Latin Old Irish Old Gothic Lithuanian Church Slavic four chaturtha tettares Quattuor cethair fidwor Keturi chetyre five Pancha pente Quinque Coic Fimf Penki Peti mother Maatra mater Mater modhir Mote Mati mathir brother Bhrataa phrater Fratera brathair brothar Brolis bratu These examples are nowhere near as obviously related -- but they are, in fact, related. The words for brother are clearer than the others: You can see that the first sound varies between b, bh (a breathy b), ph (a breathy p), and f. The first vowel varies between a and o. The middle consonant varies between t and th. In all but the last two languages, the words end in some variation of ar or er. Notice that the examples include Sanskrit (ancestor of the languages of northern India), Greek, Old Irish, and Lithuanian! Gothic is the oldest recorded version of the Germanic languages, and Old Church Slavic the oldest of the Slavic languages. There are, in fact, even more relatives, including Albanian, Armenian, the languages of Iran, and many languages which haven't survived. By examining the patterns in many languages and many words, linguists have reconstructed the Proto-Indo-European forms of these and many other words: Protoindoeuropean Kwetwer Mater Bhrater For a few more examples, here are the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European numbers from one to ten: oino, dwo, trei, kwetker, penkwe, sweks, sept, oktou, newn, dekm. Old English The primary sources for what developed as the English language were Germanic language spoken by a group of tribes from northern Europe which invaded the Britis Isles in the fifth century A.D. In one early account,these tribes of Angles. Saxons and Jutes were described as” God’s wrath toward Britain’’. From this early variety of Englisc, we have many of the most basic terms in our language: mann (man), wif (woman ), cild (child), hus (house), mete (food), etan (eat), drincan (drink) and feohtan (fight). By all account,these pagan settlers certainly liked feohtan. However, they did nit remain pagan for long. From he sixth to the eighth century, there was an extended period in which these Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity and a number of term from the language of religion, Latin, came into English at that time. The origins of the modern word angel, bishop, candle, chruch, martyr, priest and school all date from his period. From the eighth century throughtthe ninth and tenth centuries, another grup of northern Europeans came first to plunder, and eventually to settle in parts of the coastal regions of Britain. They were the vikings and it is from their language. Old Norse, that we derived the forms which gave us a number of common modern terms such as give, law, leg, skin, sky, take, and they. Middle English The event which more than anything marks the end of the Old English period, and the beginning of the Middle English period.is the arrival of the Norman French in England, following their victory at Hastings under William the Conueror in 1066. These French-speaking invaders proceeded to take over the whole of England. They became the rulling class, so that the language of the nobility, the goverment, the law and civilized behavior in England for the next two hundredyears was French. It is the source of such modern term as army, coutr, defense, faith and tax. Yet the language of the peasants remained English. The peasantworked of the land and reared sheep, cows, and swine (words from Old English),while the Frenchspeaking upper classes ate mutton,beef and ork ( word of French origin ). Hence the different word in modern English to refer to these creatures ‘on the hoof as opposed to’on the late’. Throughout this period, French (or,more accurately, an English version of French)was the prestige language and Chaucer tells us that ne of his Centerbury pilgrims could spek it. This is an example of Middle English, written in the late fourteenth century. It has changed were yet to take, place before the language took on its modern form. Most significantly : the vowel sounds of chaucer’s time were very different from those we hear in similar word today. Chaucer lived in what would have sounded like a ‘hoos’, with his ‘weef’ and hay , would romance ‘heer’ with a bottle of ‘weena’ drunk by the light of the ‘moan’. In the two hundred years, from 1400 to 1600, which separated Chaucer and Shakespeare, the sounds of English pronunciation. Whereas the types of borrowed words we have already noted are exampleof external change in a language, many of the following examples can be seens as internal changes within the historical development of English. Types of language change All languages change constantly, and do so in many and varied ways. Each generation notes how other generations "talk funny". Marcel Cohen details various types of language change under the overall headings of the external evolution and internal evolution of languages. Lexical changes The study of lexical changes forms the diachronic portion of the science of onomasiology. The on going influx of new words in the English language (for example) helps make it a rich field for investigation into language change, despite the difficulty of defining precisely and accurately the vocabulary available to speakers of English. Throughout its history English has not only borrowed words from other languages but has re-combined and recycled them to create new meanings, whilst losing some old words. Phonetic and phonological changes Main articles: sound change and phonological change The concept of sound change covers both phonetic and phonological developments. The sociolinguist William Labov recorded the change in pronunciation in a relatively short period in the American resort of Martha’s Vineyard and showed how this resulted from social tensions and processes.Even in the relatively short time that broadcast media have recorded their work, one can observe the difference between the pronunciation of the newsreaders of the 1940s and the 1950s and the pronunciation of today. The greater acceptance and fashionability of regional accents in media may[original research?] also reflect a more democratic, less formal society — compare the widespread adoption of language policies. Spelling changes Standardisation of spelling originated relatively recently.[citation needed] Differences in spelling often catch the eye of a reader of a text from a previous century. The pre-print era had fewer literate people: languages lacked fixed systems of orthography, and the handwritten manuscripts that survive often show words spelled according to regional pronunciation and to personal preference. Semantic changes Semantic changes include pejoration, in which a term acquires a negative association amelioration, in which a term acquires a positive association widening, in which a term acquires a broader meaning narrowing, in which a term acquires a narrower meaning CHAPTER IV CONCLUTION Morphology is concerned with the internal structure of words and the rules for forming words from their subparts, which are called morphemes. Language Change according to William Caxton is (ca. 1415~1422 – ca. March 1492) was an English merchant, diplomat, writer and printer. As far as is known, he was the first English person to work as a printer and the first to introduce a printing press into England. He was also the first English retailer of printed books (his London contemporaries in the same trade were all Dutch, German or French). Types of language change: Lexical changes Phonetic and phonological changes Spelling changes Semantic changes BILBLIOGRAPHY Wardaugh Ronald, 1992, An Introduction to Sociolinguistics,, Cambridge USA : blackwell oxford uk. Matthews, P. H. 1972. Inflectional morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/langevol.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language_change