Mushroom Reef Marine Sanctuary Management

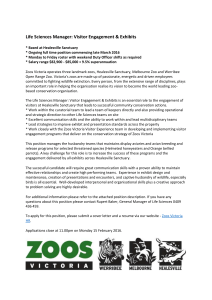

advertisement