Borderline Personality Disorder - Rachel Berry

advertisement

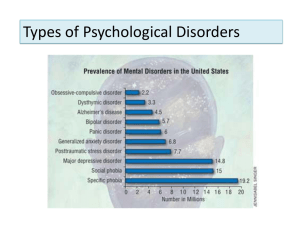

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER Running Head: BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER Literature Review on Borderline Personality Disorder Rachel Berry Wake Forest University 1 BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 2 Abstract Borderline personality disorder is a stigmatizing and debilitating Axis II, cluster-b personality disorder that affects approximately 1-2% of the general population and 10-20% of the clinical population. Borderline is considered the most dysfunctional of the personality disorders in terms of quality of life, interpersonal problems, and global functioning. The disorder is characterized by unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, affect dysregulation, and impulsivity. Little is understood about the neurobiology, genetics, and environmental factors that contribute to borderline personality disorder. A lack of clear causation, inconsistent reaction to pharmacological treatments, and variations in symptoms within and among individuals with borderline personality disorder contribute to the complicated nature of the disorder. In addition, borderline personality disorder is often comorbid with other Axis I and II disorders and can be misdiagnosed as major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. This review will provide an overview of current research on diagnosis, including controversies and diagnostic tools, and etiology of the disorder, including recent neurobiological research. It will provide an overview of treatment options, focusing specifically on mentalization-based therapy. Finally, the manuscript will identify gaps in the literature and important areas of further research. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 3 Introduction Background Borderline personality disorder is an Axis II personality disorder characterized by “a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects, and marked impulsivity” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, p. 706). A personality disorder is defined as “an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, p. 686). Borderline personality disorder is grouped with antisocial, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders in cluster b, the dramatic-emotionalerratic cluster of personality disorders. Cluster B disorders are the most common personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Borderline personality disorder is diagnosed by the presence of five or more of nine criteria. These criteria are: (1) frantically avoiding abandonment, (2) unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, (3) identity disturbance, (4) impulsivity, (5) self-injury and suicidal ideation and behavior, (6) extreme reactivity of mood, (7) chronic emptiness, (8) difficulty controlling anger, and (9) temporary episodes of paranoia and/or dissociation (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Significance Borderline personality disorder is a debilitating and stigmatizing disorder with a high negative impact on quality of life for those who have the disorder and their loved ones. Numerous studies have sought to estimate the prevalence of borderline personality disorder in the general population and in clinical settings. Estimates in the general population range from BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 4 0%-6% (Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007; Grant et al., 2008). A sound estimate appears to be between 1-2% of the general population (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Skodol et al., 2011; Biskin & Paris, 2012). Among clinical populations, people with borderline personality disorder account for 10% of mental health outpatients, 20% of psychiatric inpatients, and 30-60% of people being treated for personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). An estimated 70% of those diagnosed with borderline personality disorder are female (Biskin & Paris, 2012). Borderline personality disorder negatively impacts quality of life. Borderline is called “generally the most severely dysfunctional disorder” (First, Frances, & Pincus, 2004, p. 1251). People with borderline personality disorder experience extreme interpersonal difficulties and trouble at work. Many engage in impulsive and self-harm behaviors ranging from gambling, dangerous driving, and risky sexual behavior to cutting, burning, and suicide attempts. Among people with borderline personality disorder, the lifetime completed suicide rate is approximately 8-10% (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Borderline is often comorbid with other Axis I and Axis II disorders. Common comorbid Axis I disorders are mood disorders, substance use disorders, eating disorders (particularly bulimia nervosa), post-traumatic stress disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The most common comorbid Axis II disorders are antisocial and dependent personality disorders (McGlashan et al., 2000). In addition, dissociative symptoms occur more frequently with borderline personality disorder than with any other group (Sar, Akyuz, Kugu, Ozturk & EtemVehid, 2006; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Jager-Hyman, Reich & Fitmaurice, 2008). BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 5 Methods I conducted preliminary research using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV Text Revision and Google for overview information as well as clues as to which key words would prove fruitful in more advanced searches. The National Education Alliance Borderline Personality Disorder (NEA.BPD) (2012) is a non-profit organization that aims to raise public awareness, further research, and support those living with borderline personality disorder. The organization’s website provides a brief introduction to the disorder, including DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria and information on treatment options. The DSM-IV-TR provides information on the diagnostic criteria, comorbid disorders, prevalence, course, familial pattern, and treatment of borderline personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). After obtaining this preliminary information, I conducted keyword searches on PsycINFO and PubMED databases for sources from 2000-present. PsycINFO produced the most useful results. I initially used the keyword “borderline personality disorder” with the Boolean operator “and” combined with terms such as “techniques”, “outcomes”, “psychopathology”, “diagnosis”, “treatment effectiveness”, “psychodynamic”, “mentalization therapy”, and “dialectical behavior therapy”. Based on citation lists from initial searches, the list of keywords grew to include additional therapies such as “dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy”, “mentalization-based treatment”, “schema therapy”, “supportive therapies”, and “transferencefocused psychotherapy”. I manually sorted articles based on date of publication and perceived relevance. Many of the citation lists from these articles proved fruitful in leading me to additional sources. Sources used include book chapters from the DSM-IV-TR and DSM-IV-TR Guidebook, review articles, and original research from peer-reviewed journals. The most useful BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 6 journals proved to be the Journal of Personality Disorders and The American Journal of Psychiatry. Results Diagnosis A diagnosis of borderline personality disorder requires that symptoms developed in adolescence and early adulthood and have remained relatively stable over time. To meet the diagnosis, a person must match at least five of the nine diagnostic criteria. The first criterion is desperate attempts to avoid abandonment, whether real or imagined (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Separation threatens self-image, which leads to extreme and sudden changes in affect, cognition, and behavior. The second criterion is a history of volatile, intense relationships. People with borderline personality disorder tend to become intimate very quickly and idealize people. When someone does not live up to the imagined ideal, the person with borderline personality disorder reaches a drastic level of anger quite suddenly. While people with borderline do have an ability to care for people and form relationships, their expectations are unrealistic, leading to negative responses that are much more extreme than those of a normal person. Criterion three is identity disturbance, which manifests in a frequently changing selfimage and sense of self. People with borderline personality disorder report frequent feelings of not knowing who they are and trying to conform to what they think others wish for them to be (Lichtenstein & Peoples, 2006). A lack of identity leads them to abrupt changes in goals and values such as career, sexual identity, friend group, and activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). They often perceive themselves as evil, and many report feeling as though they do not truly exist. The fourth criterion is detrimental impulsivity in areas such as spending, sex, gambling, substance abuse, and binge eating. Impulsivity is considered distinct from the BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 7 fifth criterion, suicidal ideation and/or behavior and self-harm. Cutting and burning are common among people with borderline personality disorder. They report using self-harm as an emotional outlet to alleviate feeling states that they cannot stand and often cannot explain (Lichtenstein & Peoples, 2006). Self-harm may occur during dissociative experiences or may be a response to a threat of abandonment. Approximately 10% of people with borderline personality disorder commit suicide by age 30, a rate over fifty times higher than the general population (Biskin & Paris, 2012; Soler et al., 2009). People with borderline indicate a deep ambivalence about living and a need for others to affirm their worth (Lichtenstein & Peoples, 2006). More than half of people with borderline personality disorder abuse alcohol or drugs, which increases completed suicides (Biskin & Paris, 2012). The sixth criterion is affect instability and intense reactivity of mood (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). People with borderline personality disorder are extremely sensitive to interpersonal stress and are likely to react with dysphoria, irritability, or anxiety. These episodes normally last a few hours to a couple of days. Criterion seven is chronic feelings of emptiness. Criterion eight is difficulty controlling anger. People with this disorder often experience anger that is out of proportion to the stimulus and viewed by others as inappropriate. It is often triggered by the perception that a loved one is neglecting, abandoning, or withholding love. Eruptions of anger are characterized by bitterness, sarcasm, and verbal outbursts and are often followed by feelings of guilt, shame, and a sense of being evil or bad. The ninth criterion is paranoia or dissociation as a result of extreme stress. These episodes are not so severe and long-lasting as to merit an additional diagnosis such as paranoid personality disorder or dissociative identity disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Clinicians can diagnose borderline personality disorder using a number of structured and semi-structured interview tools. As the biological pathways of borderline personality disorder are BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 8 poorly understood, there are no laboratory or imaging tests currently available for diagnosis (Paris, 2008). At least five of the nine diagnostic criteria must have been present in the individual since adolescence or early childhood and appear in multiple areas of the person’s life (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). It is recommended that clinicians use a general personality disorder diagnostic tool initially so as to make an accurate diagnosis of a personality disorder. Borderline personality disorder can be comorbid with other personality disorders and Axis I disorders (notably mood, PTSD and bulimia nervosa). Several tools exist such as the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders, the International Personality Disorder Examination, the Personality Disorder Interview-IV, and the Structured Interview for DSM-IV-TR Personality Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The Diagnostic Interview for BorderlinesRevised (DIB-R) is a tool specifically designed to diagnose borderline personality disorder (First, Frances, & Pincus, 2004). However, this assessment can take up to two hours and is considered impractical by some clinicians. Diagnostic Difficulties and Controversies The current diagnostic criteria in the DSM-IV-TR allow for a possible 256 different combinations of symptoms, making borderline personality disorder a challenge to diagnose (Biskin & Paris, 2012). Individuals with borderline personality disorder show both stable and unstable features over time, and sometimes the same person may be re-tested with different results (Costa, Patriciu, & McCrae, 2005; Miller, Muehlenkamp, & Jacobson, 2008). Borderline personality disorder can be difficult to diagnose because it may look like a mood disorder or bipolar disorder (Biskin & Paris, 2012). In addition, high comorbidity with other Axis I and II disorders complicated diagnosis. Borderline personality disorder is frequently comorbid with major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, bulimia nervosa, post-traumatic BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 9 stress disorder, and schizotypal, dependent, antisocial, and narcissistic personality disorders (Grant et al, 2008; First, Frances, & Pincus, 2004). The literature raises questions as to a possible relationship between borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder, a link that has been largely discredited. Paris, Gunderson, and Weinberg (2007) conducted a review comparing the two disorders’ etiology, response to medication, family prevalence, and course and found that the two disorders to be distinct. The overall courses of the disorders are distinct, and there is no statistically significant indication that one disorder evolves into the other over time. Additionally, family studies reveal that each disorder is heritable, but families tend to show a prevalence of either borderline or bipolar but not both. Finally, certain characteristics such as impulsivity, drastic changes in mood, and harm avoidance are distinct between the disorders. People with borderline personality disorder seek to avoid harm, a trait not present in bipolar disorder (Atre-Vaiydya & Hussain, 1999). Additionally, bipolar II involves mood swings to euphoria, a state experienced briefly if at all by borderline individuals (Koenigsberg et al., 2002). While individuals with both disorders show impulsive behaviors, in bipolar disorder impulsivity is episodic compared to the recurring pattern of impulsivity in borderline individuals (Swann, Pazzaglia, Nicholls, Dougherty, & Moeller, 2003; Brown, Comtois, & Linehan, 2001). New, Triebwasser, & Charney (2008) argue to shift borderline personality disorder to an Axis I diagnosis. Borderline personality disorder has been classified as an Axis II diagnosis since it was first included in the DSM-III in 1980 (Oldham, 2009). At that time, the field of mental health believed that the personality disorders were caused by early trauma. More recent evidence points to genetic origins of borderline personality disorder in which an individual’s genetic predisposition towards certain traits is compounded by environmental stressors. In one BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 10 twin study by Torgersen (2000) showed that 69% of the variance in borderline personality disorder is genetic. New, Triebwasser, & Charney (2008) argue that there is a lack of empirical evidence to suggest distinguishing Axis I disorders from Axis II disorders. Additionally, individuals with borderline personality disorder differ from those with other personality disorders in that they frequently seek treatment, in large part because their thoughts and behaviors are contrary to the needs of the ego (Paris, 2007). Although the authors make several valid points, it appears that their primary motivation is to encourage more funding and research into borderline personality disorder. While this is a worthwhile goal, reclassifying mental disorders on this basis is a slippery slope. The Personality and Personality Disorders Work Group for the DSM-V do not argue for the reclassification of borderline personality disorder to Axis I (Skodol et al., 2011). The authors propose five personality disorders including borderline for the DSM-V. Each of these disorders is “identified by core impairments in personality functioning, pathological personality traits, and common symptomatic behaviors”(Skodol et al., 2011, p. 136). The authors concede that DSMIV-TR personality diagnoses employ arbitrary thresholds and that diagnostic criteria are neither empirically based nor specific enough. The DSM-IV-TR definition of personality disorder indicates that symptoms are stable, but longitudinal studies show this not to be the case. However, Skodol et al. (2011) argue that borderline personality disorder is “ a unidimensional construct” and that borderline personality disorder represents “a distinct disorder, yet one with dimensionally distributed temperamental characteristics” (p. 141). Based on data from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS), the three main components of borderline personality disorder are interpersonal problems, behavioral dysregulation, and affect dysregulation (Skodol et al., 2002). As this research is more recent than the 2008 article by BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 11 New, Triebwasser, and Charney and conducted by the DSM-V workgroup, borderline personality disorder will most likely continue to be classified as an Axis II personality disorder for the foreseeable future. Misconceptions about Borderline Personality Disorder Borderline personality disorder is widely misunderstood due to its complex nature, lack of knowledge of its causes, and resistance to treatment (both psychotherapy and medication). The name borderline personality disorder was originally used by Adolf Stern in 1938 and was expanded in the 1960s-1970s by Otto Kernberg (Stern, 1938; Kernberg, 1970). Borderline personality disorder was originally conceptualized as being on the border between mental states, but this is no longer considered to be the case (Paris, 2007). Specifically, people with borderline personality disorder were originally conceived as lapsing into schizophrenic-like states (Gunderson, 2009). However even before it was first included in the DSM-III, researchers realized it was unrelated to schizophrenia. Another area of confusion in borderline personality disorder is the relationship between the disorder and childhood trauma or neglect. The DSM-IV-TR states, “Physical and sexual abuse, neglect, hostile conflict, and early parental loss or separation are more common in the childhood histories of those with borderline personality disorder” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, p. 708). However, family studies and neurobiological research cast doubt on a purely causal relationship between early childhood stressors and borderline personality disorder. A bidirectional relationship between genetic predisposition towards certain traits and the presence of environmental stressors is more likely (Fonagy, Luyten, & Strathearn, 2011). 2045% of people with borderline personality disorder report no history of sexual abuse, and 80% of people with a history of sexual abuse do not exhibit symptoms of personality pathology BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 12 (Goodman & Yehuda, 2002; Paris 1998). As borderline personality disorder has been shown to run in families, it is possible that individuals with borderline were abused or neglected as children by a caregiver who also shows traits of the disorder. Additionally, people with borderline tend to conceptualize life events negatively, leading to possible negative self-report bias among adults recalling childhood memories (New et al., 2008). Genetics, Neurobiology, and the Environment Although researchers have found that genetics play a significant role in borderline personality disorder, there remain no unifying neurobiological theory and no biological markers or imaging tests for the disorder (Gunderson, 2009; Biskin & Paris, 2012). Brain scans show irregularity in the brains of individuals with borderline personality disorder. Donegan et al. (2003) have found that people with borderline personality disorder have a hyperactive amygdala, leading to oversensitive reactions to facial expressions. Indeed, individuals with borderline personality disorder often perceive neutral faces as negative. Other studies have shown abnormalities in parts of the brain that regulate emotions such as the anterior cingulate gyrus and the orbital frontal cortex (New et al., 2008). Skodol et al. (2011) suggest that abnormal serotonin functioning lead to a lack of impulse-control and aggression in people with borderline personality disorder. Several studies have shown a link between brain reward circuits for dopamine and oxytocin and attachment, the importance of which is noted by Fonagy et al. (2011; Champagne et al., 2004; Ferris et al., 2005; Strathearn, Li, Fonagy, & Montague, 2008; Bartels & Zeki, 2004; Champagne, Diorio, Sharma, & Meaney, 2001, Levine, Zagoory-Sharon, Feldman, & Weller, 2007). Of interest to clinicians and neuroscientists alike is borderline personality disorder’s resistant to pharmacological treatment. If a mental disorder responds to a drug, one can learn BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 13 more about the neurological pathways of the disorder based on what is known about the way the drug works in the brain. Individuals with borderline personality disorder respond differently to different medications, and sometimes the response is only temporary (New et al., 2008). Additionally, drugs from a wide variety of psychotropic classes have proven effective. A lack of consistent and effective drug treatments for borderline personality disorder points to the lack of knowledge of the brain biology. It is a compelling argument for further research into the neurobiology of the disorder and effective psychotherapeutic treatments. Fonagy et al. (2011) propose a bidirectional relationship between neurobiology and the environment, manifested in unstable and hyper reactive attachment and a lack of mentalization. The hormone oxytocin activates attachment, deactivates social avoidance, reduces responses to stress, aids in mentalization, and enhances social memory and recognition of facial expressions (Heinrichs & Domes, 2008; Fonagy, Gergely, & Target, 2007; Gergely, 2007; Heinrichs & Gaab, 2008; Domes, Heinrichs, Michel, Berger, & Herpertz, 2007). Attachment is crucial for the development of self-structure and the ability to manage stress. The authors characterize individuals with borderline personality disorder as having “attachment hyper activating strategies”, predisposing them to highly intense interpersonal relationships coupled with panicked efforts to avoid abandonment (Fonagy et al., 2011, p. 55). In the absence of secure attachment as children, the authors propose, borderline individuals do not establish a consistent sense of self and often resort to splitting. Without healthy attachment, children do not achieve the developmental milestone of basic trust (Oldham, 2009). If an infant is predisposed to poor self-regulation, Fonagy et al. (2011) argue this will cause difficulties developing self-control and mentalization. Mentalization is defined as understanding the mental states of self and others. It is also possible that mentalization and BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 14 empathy were not taught to children with borderline personality disorder. Another theory is that children who are abused and neglected avoid learning to mentalize in order to cope with abuse and neglect. Understanding the mental states of abusive caretakers would be maladaptive and too painful for a child, which could then lead to poor mentalization and splitting. Psychotherapeutic Treatment Although people with borderline personality disorder are often motivated to seek treatment, working with people with this disorder is challenging for clinicians. In clinical trials, six types of psychotherapy have shown efficacy for treating borderline personality disorder: mentalization-based therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, transference-focused therapy, schemafocus therapy, supportive psychotherapy, and Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (Gabbard & Horowitz, 2009). Given the variety of symptomatic presentation among individuals with borderline personality disorder, it is advisable to consider tailoring therapeutic approaches to the individual (Higa & Gedo, 2012; Oldham, 2009). A full discussion of the various treatments is beyond the scope of this review. As Fonagy et al. (2011) and others argue that key components in borderline personality disorder are insecure attachment and an inability to mentalize, this review focuses on mentalization-based therapy. Higa and Gedo (2012) argue that learning to mentalize is an important first step toward improved outcomes in individuals with borderline personality disorder. By focusing on the client’s current mental state, clients can learn the skills of introspection and self-agency (Gabbard & Horowitz, 2009). Proponents of mentalization-based therapy believe that a client who cannot mentalize cannot handle transference interpretations and may become destabilized (Gunderson, Bateman, & Kernberg, 2007). As transference-focused therapy may cause overwhelming negative emotions in borderline individuals, first using mentalization-based therapy can strengthen later BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 15 transference interpretations. In one case study, Higa and Gedo (2012) observed that clients responded better to mentalization-based therapy early in treatment or when regressing and that transference-focused therapy was more effective once the client learned to mentalize. Mentalization can help individuals with borderline personality disorder better handle interpersonal relationships, impulses, and affective dysregulation. A central tenet of mentalization-based therapy is a focus on “mental resources that are available to deal with recurrent patterns of behaviour [sic] and relationships rather than ideation of the patterns themselves” (Bateman, Ryle, Fonagy, & Kerr, 2006, p. 59). The goal of mentalization-based therapy is to help clients reflect on their cognitions and emotions before acting in order to gain control over their automatic responses to situations (Gabbard & Horowitz, 2009). The clinician teaches the client to mentalize, a process the client can then use in other experiences and relationships. Rather than merely bestowing interpretations, the clinician helps the client develop a capacity to think differently about his or her interactions. The capacity to mentalize is considered a developmental milestone, and the failure to achieve this milestone is thought to be a significant component in the development of borderline personality disorder. This can be helped by learning to mentalize, which assists the individual in developing a stronger self-concept and understanding the thoughts of self and others. Mentalization allows clients to accept the therapist’s perspective, allowing the client to handle transference-interpretation and insight from the clinician. Understanding mental states will transfer to the client’s outside relationships, giving the client new ways to cope with intense emotional reactions and create healthier attachment. As volatile interpersonal dynamics are a key symptom of borderline personality disorder, mentalization appears to be a critical step towards amelioration of difficulties. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 16 Discussion Based on the literature, borderline personality is a viable diagnostic construct with three primary features of disturbed relatedness, difficulty regulating affect, and difficulty regulating behavior. Based on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAFS), people with borderline personality disorder have the greatest functional impairment, which stays relatively stable (Skodol et al., 2011). Individuals with borderline personality disorder experience greater troubles at work and in interpersonal relationships. Borderline personality disorder is a prevalent and debilitating condition that merits greater attention and funding. It occurs in as much as 6% of the population and in 30-60% of clinical populations with personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In addition to its prevalence, the disorder proves highly dangerous to individuals who suffer from it. Self-harm behavior such as burning and cutting is found in over 90% of those with the disorder, and more than 50% abuse drugs or alcohol. Impulsive and dangerous behaviors increase the risk of successful suicide in borderline individuals, and the lifetime completed suicide rate is close to 10% (Biskin & Paris, 2012). While researchers and clinicians generally agree on its continued utility and inclusion in the DSM, much remains unclear about borderline personality disorder. The DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria allow for a vast combination of symptoms, and symptoms are not necessarily consistent over time. Borderline personality disorder responds inconsistently to a wide range of psychotropic drugs and psychotherapeutic treatments. While a history of abuse or trauma is common in individuals with borderline personality disorder, research casts doubt on the exact relationship between negative early events and the disorder. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 17 Unstable early attachment relationships and a lack of mentalization appear to be important factors in the development of borderline personality disorder, as argued by Fonagy et al. (2011). As such, mentalization-based therapy appears to be a successful intervention either alone or in tandem with other treatment types. Researchers should conduct additional clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of mentalization-based therapy by itself or with other types of treatments. By combining aspects of various treatments with proven clinical efficacy, clinicians can potentially improve outcomes for individuals with borderline personality disorder. A major area for further research is the etiology of the disorder. Until more is known about the genetic, neurobiological, and environmental influences on the development of the disease, attempts at treatment are based on trial and error. When researchers learn more about the causes of the disorder, clinicians can educate the public, diagnose earlier, and develop more successful treatment. Individuals with borderline personality disorder frequently pursue treatment due to the ego dystonic nature of the disease, and clinicians need to be ready with effective interventions. Researchers should also conduct studies to investigate the cognitive symptoms of borderline personality disorder (Biskin & Paris, 2012). Observed cognitive features include dissociation (occurring in as many as 50% of borderline individuals), depersonalization, and derealization. These cognitive features may be related to an unstable self-image and maladaptive coping strategies. Symptoms appear to result from stress, particularly interpersonal stress. Research into the cognitions of individuals with borderline personality disorder may help mental health professionals develop effective treatment interventions and understand the causes and course of borderline personality disorder. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 18 Another area for research in the near future is a continued exploration of effective interventions in treatment. By comparing treatment modalities among individuals with different symptom presentations and traits, researchers can guide clinicians towards effective treatment planning for borderline clients. No one treatment is effective for every borderline client, and research shows that often a combination of treatments is most effective. In clinical trials, results are often based on mean values that fail to distinguish the ways individual patients responded (Gabbard & Horowitz, 2009). Thus in addition to new clinical trials, re-examining past research may prove fruitful in determining which therapies are most effective with which types of borderline individuals. Reference List American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: Author. Atre-Vaiyda, N., & Hussain, S.M. (1999). Borderline personality disorder and bipolar mood disorder: two distinct disorders or a continuum. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(5), 313-357. Bartels, A., & Zeki, S. (2004). The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. Neuroimage, 21(3), 1155-1166. Bateman, A.W., Ryle, A., Fonagy, P., & Kerr, I.B. Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Mentalization based therapy and cognitive analytic therapy compared. International Review of Psychiatry, 19(1), 51-62. doi: 10.1080/09540260601109422 BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 19 Biskin, R.S. & Paris, J. (2012). Diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Canadian Medical Association Journal. Advanced online publication. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090618 Brown, M.Z., Comtois, K.A., & Linehan, M.M. (2002). Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 198-202. Champagne, F.A., Chretien, P., Stevenson, C.W., Zhang, T.Y., Gratton, A., & Meaney, M.J. (2004). Variations in nucleus accumbens dopamine associated with individual differences in maternal behavior in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(17), 4113-4123. Champagne, F., Diorio, J., Sharma, S., & Meaney, M.J. (2001). Naturally occurring variations in maternal behavior in the rat are associated with differences in estrogen-inducible central oxytocin receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 98, 1273612741. Costa, P.T., Jr., Patriciu, N.S., & McCrae, R.R. (2005). Lessons from longitudinal studies for new approaches to the DSM-V: The FFM and FFT. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(5), 533-539. Domes, G., Heinrichs, M., Michel, A., Berger, C., & Herpertz, S.C. (2008). Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biological Psychiatry, 61(6), 731-733. Donegan, N.H., Sanislow, C.A., Blumberg, H.P., Fulbright, R.K., Lacadie, C., Skudlarski, P., …. Wesler, B.E. (2003). Amygdala hyperreactivity in borderline personality disorder: Implications for emotional dysregulation. Biological Psychiatry, 54(11), 1284-1293. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00636-X Ferris, C.F., Kulkarnic, P., Sullivan, J.M., Harder, J.A., Messenger, T.L., & Febo, M. (2005). Pup suckling is more rewarding than cocaine: Evidence from functional magnetic BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 20 resonance imaging and three dimensional computational analysis. Journal of Neuroscience, 25, 149-156. First, M.B., Frances, A., & Pincus, H.A. (2004). DSM-IV-TR guidebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publication. Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., & Target, M. (2007). The parent-infant dyad and the construction of the subjective self. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(3-4), 288-328. Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., & Strathearn, L. (2011) Borderline personality disorder, mentalization, and the neurobiology of attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 32(1), 47-69. doi:10.1002/imjh.20283 Gabbard, G.O., & Horowitz, M.J. (2009). Insight, transference-interpretation, and therapeutic change in the dynamic psychotherapy of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(5), 517-521. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050631 Gergely, G. (2007). The social construction of the subjective self: The role of affect-mirroring, markedness, and ostensive communication in self development In L. Mayes, P. Fonagy, & M. Target (Eds.), Developmental science and psychoanalysis (pp. 45-82). London: Karnac. Goodman, M., & Yehuda, R. (2002). The relationship between psychological trauma and borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Annals, 32(6), 337-346. Grant, B.F., Chou, S.P., Goldstein, R.B., Hunag, B., Stinson, F.S., Saha, T.D., …. June, W. (2008). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(4), 533-545. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 21 Gunderson, J.G. (2009). Borderline personality disorder: Ontogeny of a diagnosis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(5), 530-539. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121825 Gunderson, J.G., Bateman, A., & Kernberg, O. (2007). Alternative perspectives on psychodynamic psychotherapy of borderline personality disorder: The case of “Ellen”. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(9), 1333-1339. Heinrichs, M., & Domes, G. (2008). Neuropeptides and social behaviour: Effects of oxytocin and vasopressin in humans. Progress in Brain Research, 170, 337-350. Heinrichs, M., & Gaab, J. (2007). Neuroendocrine mechanisms of stress and social interaction: Implications for mental disorders. Current Opinions in Psychiatry, 20(2), 158-162. Higa, J.K., & Gedo, P.M. (2012). Transference interpretation in the treatment of borderline personality disorder patients. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 76(3), 195-210. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2012.76.3.195 Kernberg, O.F. (1970). A psychoanalytic classification of character pathology. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 18(4), 800-822. Koenigsberg, H.W., Harvey, P.D., Mitropolou, V., Schmeidler, J., New, A.S., Goodman, M., et al. (2002). Characterizing affective instability in borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(5), 784-788. Lenzenweger, M.F., Lane, M.C., Loranger, A.W., & Kessler, R.C. (2007). DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 62(6), 553-564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019 Levine, A., Zagoory-Sharon, O., Feldman, R., & Weller, A. (2007). Oxytocin during pregnancy and early postpartum: Individual patterns and maternal-fetal attachment. Peptides, 28, 1162-1169. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 22 Lichtenstein, B., & Peoples, J. (Producers). (2006). Back from the edge: Living with and recovering from borderline personality disorder [motion picture]. United States: NewYork Presbyterian Hospital. McGlashan, T.H., Grilo C.M., Skodol, A.E., Gunderson, J.G., Shea., M.T., Morey, L.C., et al. (2000). The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102, 356-264. Miller, A.L., Muehlenkamp, J.J., & Jacobson, C.M. (2008). Fact or fiction: Diagnosing borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 969981. National Education Alliance Borderline Personality Disorder. (2012). National Education Alliance Borderline Personality Disorder. Retrieved from http://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.com/ New, A.S., Triebwasser, J., & Charney, D.S. (2008). The case for shifting borderline personality disorder to axis I. Biological Psychiatry, 64(8), 653-659. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.020 Oldham, J.M. (2009). Borderline personality disorder comes of age. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(5), 509-511. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020262 Paris, J. (2008). Treatment of borderline personality disorder: A guide to evidence-based practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Paris, J. (2007). The nature of borderline personality disorder: Multiple, dimensions, multiple symptoms, but one category. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21(5), 457-473. Paris, J. (1998). Does childhood trauma cause personality disorders in adults? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 43(2), 148-153. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 23 Paris, J., Gunderson, J., & Weinberg, I. (2007). The interface between borderline personality disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(2), 145-154. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.10.001 Sar, V., Akyuz, G., Kugu, N., Ozturk, E., & Ertem-Vehid, H. (2006). Axis I dissociative disorder comorbidity in borderline personality disorder and reports of childhood trauma. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(10), 1583-1590. Skodol, A.E., Bender, D.S., Morey, L.C., Clark, L.A., Oldham, J.M., Alarcon, R.D., …. Siever, L.J. (2011). Personality disorder types proposed for DSM-5. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(2), 136-169. doi:10.1521/pedi.2011/25.2.136 Skodol, A.E., Gunderson, J.G., McGlashan, T.H., Dyck, I.R., Stout, R.L., Bender, D.S., …. Oldham, J.M. (2002). Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(2), 276-283. Soler, J., Pascual, J.C., Tiana, T., Cebria, A., Barrachina, J., Campins, M.J., …. Perez, V. (2009). Dialectical behaviour therapy skills training compared to standard group therapy in borderline personality disorder: a 3-month randomised controlled clinical trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(5), 353-358. Stern, A. (1938). Psychoanalytic investigation of and therapy in the border line group of neuroses. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 7, 467-489. Swann, A.C., Dougherty, D.M., Pazzaglia, P.J., Pham, M., & Moeller, F.G. (2004). Impulsivity: a link between bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Bipolar Disorder, 6(3), 204-212. Torgersen, S. (2000). Genetics of patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(1), 1-9. BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER 24 Zanarini, M.C., Frankenburg, F.R., Jager-Hyman, S., Reich, D.B., & Fitzmaurice, G. (2008). The course of dissociation for patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects: A 10-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavica, 118(4), 291-296.