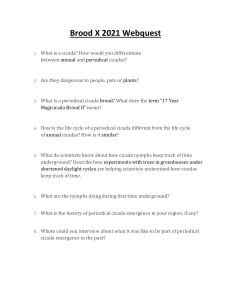

Periodical Cicadas Redux

advertisement

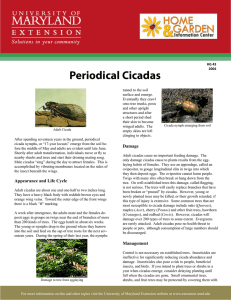

Periodical Cicadas Redux The subject of this article is not the annual or “dog day” cicadas that we hear every summer, almost everywhere. Annual cicadas are not only a different species than periodical cicadas, they are a different genus—Tibicen. Periodical cicadas are members of the genus Magicicada. Periodical cicadas are a little smaller than the annuals. They have distinctive bright orange wing veins and red eyes. There may also be some orange coloration on the body. There are eight broods of periodical cicadas that appear in Pennsylvania. The emergence of each individual brood is 17 years apart, but you can find some brood or other emerging somewhere in the state every few years. The periodicals appear earlier in the year than the annuals; the bulk of them emerge during June. The annual cicadas generally start their emergence in early-July, and there may be some overlap with the periodicals. The next brood of periodical cicadas to appear in Pennsylvania will be in the far western part of the state in 2016. Then there will be a brood in Southeastern Pennsylvania in 2017. I’ve written here before about having hit a wonderful emergence of periodical cicadas on Spruce Creek and the Little Juniata in 2008. This was, in the words of John Gierach, a cosmic experience. The big, prehistoric-looking bugs were everywhere. They buzzed around the tree canopy, and hung on streamside bushes like berries. It was easy to find their empty nymphal shucks on tree trunks, and holes in the ground at the base of the tree from which the nymphs had emerged. Every once in a while I’d feel a cicada crawling up the back of my neck. Eeewwww! Thank heaven they don’t bite, but it’s still pretty creepy. Not enough to keep me away, though. The cicadas would begin to sing as soon as the sun hit the treetops in the morning, and did not stop until the sun set in the evening. There was a non-stop humming that sounded like a fleet of alien spacecraft. Every once in a while a cicada would fly out over the stream, run out of gas, and flutter down and land on the water. The fish were waiting. Within seconds the bug would disappear in a slurping riseform, and sometimes it was apparent that it was not a small fish that caused it. A hole would open in the water, and there would be a sound reminiscent of a toilet flushing. I’d seen riseforms described that way in magazine articles, and dis-missed it as hyperbole. Not anymore. Most interesting was the consistency of this activity. Big trout that would normally feed only at night, or maybe at dawn and dusk, were active all day long. The easy availability of so many big bites of food was too much to resist, and their normal caution was overcome by greed. The bellies of landed fish felt lumpy due to their digestive tracts being stuffed with cicadas. I never caught so many big trout on surface flies in my life. I’m hesitant to refer to the cicada imitations as “dry flies.” Although they are fished floating, they are anything but delicate. These clunky foam creations are tied on size 6 or 8 hooks. We fished them on a 5-weight rod and 3X tippets. The artificials we tied and used are actually a bit smaller than the naturals. If you tied an imitation that was accurate in size and shape, you’d have to fish it on a 7weight rod and a bass leader. My largest trout landed was a 23-inch rainbow. I hooked and lost a brown trout that was much larger than that. I got a very good look at this fish. It wasn’t more than two rod lengths away from me when it drifted out from under a bankside willow, loomed up under my cicada, and sucked it in. That powerful image is permanently burned into my memory. I also got very close as I at-tempted to disentangle my leader from the branch this huge trout ultimately wrapped it around. The fish took exception to my ever-so-cautious approach and promptly broke me off—not the 3X tippet but the heavier leader above it—with a contemptuous jerk of its massive head. Understandably I was very anxious to have more of this fishing. Research indicated that a periodical cicada brood was expected in Southcentral Pennsylvania in 2012, and yet another in the Southeastern part of the state in 2013. You can find a list of each brood, and in what year and what Pennsylvania counties it is expected, on the Penn State website. The problem, I have learned, is that there is a lot more to it than that. The cicadas are not uniformly distributed throughout the counties where they occur. They can be very abundant in one location and completely absent just a few miles away. What you need is to find a place where a heavy emergence coincides in location with fishable water. That is not so easy. The adult cicadas are only around for a few weeks, just long enough to mate and deposit eggs. Their progeny then spend the next 17 years as nymphs, attached to tree roots from which they obtain sustenance. Anglers who are lucky enough to find a fishable emergence tend, quite understandably, to be closedmouthed about it. In many cases, by the time you find out it’s over or soon will be. In 2011 I sent an e-mail to Penn State fly fishing entomologist Greg Hoover, asking if he could tell me what streams might produce fishing to the cicadas during the 2012 and 2013 emergences. Greg kindly responded, but said that he had bad news. He had no records of either of these emergences producing good fishing. I didn’t try too hard to find the 2012 emergence. It would have involved a lot of travel that I wasn’t in a position to do. I made a few inquiries with people I thought might have their finger on the emergence, but no useful information was forthcoming. Since the 2013 emergence was more widespread, and closer to home, I made a much more serious effort. I did a lot of on-line research, and ran down leads from several sources. I made a list of places where I thought I might find the cicadas. One such spot was the Lehigh River. I booked a float trip with Joe DeMarkis of Rivers Outdoors, but Joe called a couple of days before our date to say that the Lehigh was blown out with run-off and not likely to improve soon. I later found out, after it was all over, that the cicadas had indeed been on the Lehigh. This is not a river I want to wade, however, especially if it’s too high to float! I did not find cicadas on the upper Bushkill, when I was invited by my friends Jeanne Ludlow and Jack Bergin for a weekend at the Mink Pond Club. However, I did see them flying over Route 33 in the Wind Gap area as I drove home. I think I even had a few bounce off my windshield. I kept up my research, hoping to fit some cicada hunting in with other commitments during June. No one on the fly fishing bulletin boards was giving anything up. When Rabbit Jensen and I attended the annual Heritage Day at the PA Fly Fishing Museum on June 15, however, I got a hot tip. Rabbit and I were doing tying demos in the Museum, and we passed the time pleasantly chatting with a gentleman who was also tying there. We got on the subject of the cicadas, and he showed us his very impressive pattern for them. It was a much more accurate imitation than my pattern. As good as it looked, however, it was big and heavy, coated with epoxy, and looked like it would be rather difficult to cast on trout tackle. This fellow very kindly shared with me the information that periodical cicadas were emerging along Clark’s Creek. I was excited to hear this news. I was staying with my friend Janice Egeland in Hershey. This is a fairly short drive from Clark’s Creek, which flows into the Susquehanna on the west side of Harrisburg. On the morning of Monday, June 17, I bid Janice a fond farewell after breakfast and headed for Clark’s. Unfortunately she had business matters to attend to and could not join me. It’s a six-mile drive up a rural road that parallels the creek to get to the special regulations area. I started up the road, and after a while I pulled over and got out of the car to listen. There was that distinctive hum. And then I saw some cicadas in the air. Hot diggity, it was true! I’d found them! Clark’s is a completely different situation than Spruce and the Little J. It’s a much smaller stream, mostly under tree canopy, and the water is mostly shallow and very clear. Under normal circumstances Clark’s has a reputation for being rather technical and difficult. I had many, many hits but my hooking percentage with the oversized fly was not good. My biggest fish was about 14 inches; most were smaller. I’d say the trout I caught averaged about 10 to 11 inches. A fish of that size has to attack with serious intent to get hooked on a fly that large. Clark’s is well-stocked by a local Cooperative Nursery. I got browns, brooks, and rainbows as well as some impressive fall-fish. Even though I failed to convert the majority of my takes, there were so many that I still brought plenty of fish to hand. It was a wonderful day of fishing. I had ample opportunity to observe the insects, both on land and water. I saw nymphal shucks, the holes from which they’d emerged, and adults. I was fascinated to see that the naturals that fell into the water tended to float on their backs—upside down, with wings open. My foam cicada imitation, with its spread Krystal Flash wing, gave a pretty good impression of the natural. I’m hoping I’ll get to fish over periodical cicadas yet again. I don’t think I’ll ever get enough of it, I’m quite addicted. I may or may not make the trip out to Western Pennsylvania for the 2016 emergence there. I will definitely have my radar up for the 2017 emergence here in the Southeast, however. I’d urge any fly fisher to do the same. This is a not-to-be-missed experience. --Mary S. Kuss-