Transcript of video

advertisement

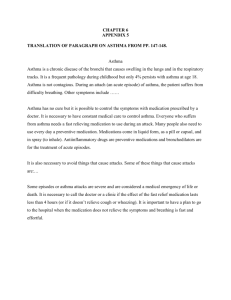

Paediatric Asthma 1: Diagnosing Asthma in Children, Dr Rahul Chodhari Speaker Key RC IV Rahul Chodhari Interviewer RC My name is Rahul Chodhari. I’m a paediatrician. The talk today was about management of wheezing children in a primary care setup. IV How can you differentiate between viral induced wheeze and asthma? RC Approach to a wheeze in primary care environment is about age at which a wheezing child presents. So, generally speaking, under five years of age, we would think more about viral induced wheeze and as school-going children with ongoing wheezing spectrum is thought more on the line of asthma. Viral induced wheeze can be triggered by either common viruses and sometimes there are other factors, such as cold or pollen or smoke. On the other hand, asthma is a chronic respiratory disease, resulting into an airflow obstruction in the lung, which mostly manifests as night-time coughing, tightness of the chest, difficulty in breathing and requires a medication to relieve the airflow obstruction. IV How would you diagnose virally induced wheeze and asthma in primary care? RC Viral induced wheeze, which is often precipitated by viruses, tends to improve over a period of time whereas viral induced wheeze, which has got other triggers, such as cold, smoke or pollens, tend to go towards a diagnosis of asthma. It is not easy to make the diagnosis in one single consultation and it is a time and a journey, which makes a difference, in terms of knowing which children will have a chronic asthma. IV How could it present? RC A common presentation of wheezing disorders in children is with breathlessness, noisiness of the sounds, poor feeding and in school-going children, often losing out on school attendance. Families would also report that their children are not able to do exercise in a way they are able to do when they’re well. IV What tests are there in primary care to enable diagnosis? RC Diagnosis of viral induced wheeze or in asthma is largely clinical and a key part of the diagnosis for asthma in a school-going child is to think about is there a high probability of asthma or a low probability of asthma? Features, which will suggest that there is a high probability of asthma, include episodes of tightening of chest, wheezing, coughing at night-time, response to the inhalers, and sometimes poor growth. 1 IV Are there any common pitfalls in diagnosis to try and avoid? RC For primary care setup, it’s worth thinking, asthma is very common so it does get mislabelled as well but for all practical purposes, a dry cough in a community environment is rarely because of an asthma. It’s also worth exploring what parents mean by wheeze; in many studies, it has been found that upper respiratory tract symptoms are misinterpreted by parents as a wheeze. And clarifying parents’ perception is quite important before labelling a diagnosis of asthma. IV Once diagnosed, what should a GP do next? RC There’s a pragmatic approach of use of medication and a review. It’s also worth thinking about what is our aim when we diagnose for the families. So, pragmatic approach is, if you do start the treatment, such as an inhaled corticosteroid, it’s good practice to do a review in six–eight weeks’ time, with two possible outcomes: Either there is a possibility that you may be able to reduce the inhaler dose, or you may need to keep it same or consider a referral if there is not a significant improvement. The aim of our treatment is to offer children a good quality of life, such as excellent school attendance, excellent exercise tolerance and reduction in symptoms such as night-time coughing. IV Are there any important differential diagnoses? RC There are many number of diagnoses, but the key ones, which are often underreported, under-looked for, are upper airway problems, such as allergic rhinitis; there is a good experience suggesting that children with allergic rhinitis symptoms are regularly offered inhalers, with poor response to it. And it’s important to recognise that the wheeze is not what families are interpreting, upper airway symptoms and it’s confirmed on auscultation. IV If it’s not asthma, what else could it be? RC There are few indicators in clinical diagnosis, which would help to suggest there’s low probability of asthma with differential diagnosis. For example, symptoms, which present from birth or a perinatal period usually suggest that this is not due to asthma and other causes. Or, if you have an episode where you’re having hyperventilation or tingling and a very poor response to the inhaled medication, it’s probably due to other causes as well and it’s worth thinking about upper airway sounds, which are regular after infection or allergic rhinitis symptoms, which are often treated with asthma medication without much of a good response. IV Where can GPs find out more? RC There’s quite a lot of information available but the key websites, which can help are NICE guidance on asthma’s management in children, British Thoracic Society’s October 2014 update on asthma, and for family resource, Asthma UK is excellent. GP surgeries are welcome to contact me on 0207 830 2211 or on email: r.chodhari@nhs.net. 2