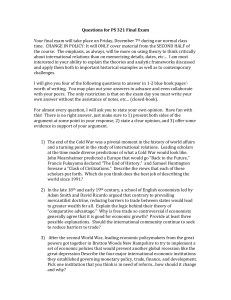

Recent Developments in Terrorism

advertisement

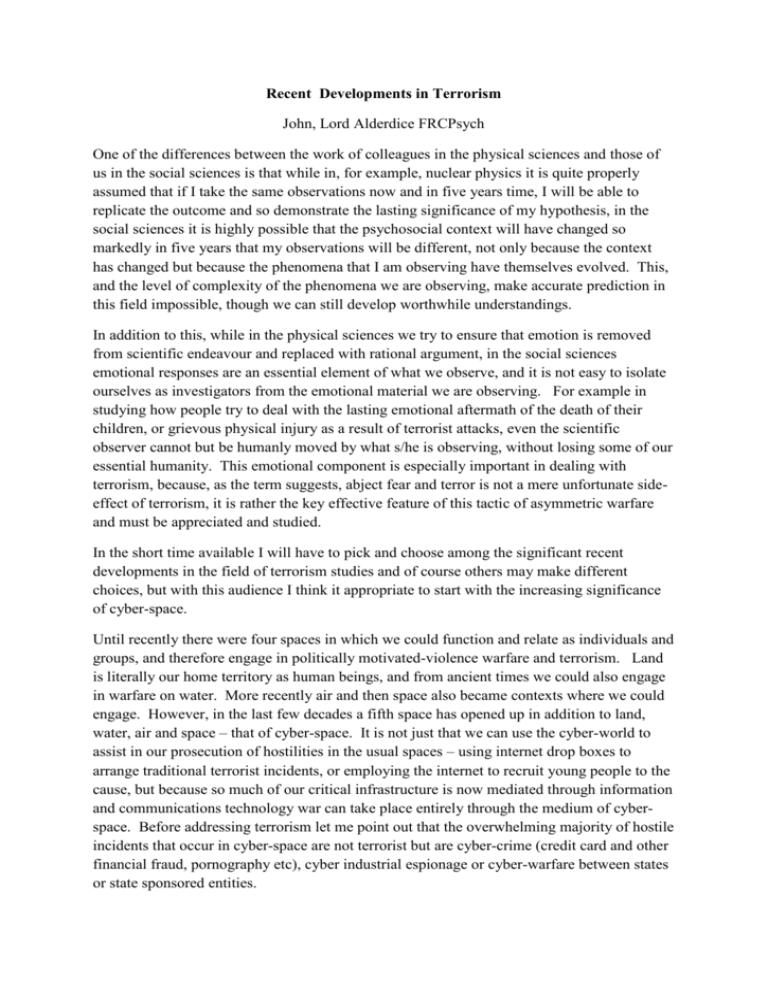

Recent Developments in Terrorism John, Lord Alderdice FRCPsych One of the differences between the work of colleagues in the physical sciences and those of us in the social sciences is that while in, for example, nuclear physics it is quite properly assumed that if I take the same observations now and in five years time, I will be able to replicate the outcome and so demonstrate the lasting significance of my hypothesis, in the social sciences it is highly possible that the psychosocial context will have changed so markedly in five years that my observations will be different, not only because the context has changed but because the phenomena that I am observing have themselves evolved. This, and the level of complexity of the phenomena we are observing, make accurate prediction in this field impossible, though we can still develop worthwhile understandings. In addition to this, while in the physical sciences we try to ensure that emotion is removed from scientific endeavour and replaced with rational argument, in the social sciences emotional responses are an essential element of what we observe, and it is not easy to isolate ourselves as investigators from the emotional material we are observing. For example in studying how people try to deal with the lasting emotional aftermath of the death of their children, or grievous physical injury as a result of terrorist attacks, even the scientific observer cannot but be humanly moved by what s/he is observing, without losing some of our essential humanity. This emotional component is especially important in dealing with terrorism, because, as the term suggests, abject fear and terror is not a mere unfortunate sideeffect of terrorism, it is rather the key effective feature of this tactic of asymmetric warfare and must be appreciated and studied. In the short time available I will have to pick and choose among the significant recent developments in the field of terrorism studies and of course others may make different choices, but with this audience I think it appropriate to start with the increasing significance of cyber-space. Until recently there were four spaces in which we could function and relate as individuals and groups, and therefore engage in politically motivated-violence warfare and terrorism. Land is literally our home territory as human beings, and from ancient times we could also engage in warfare on water. More recently air and then space also became contexts where we could engage. However, in the last few decades a fifth space has opened up in addition to land, water, air and space – that of cyber-space. It is not just that we can use the cyber-world to assist in our prosecution of hostilities in the usual spaces – using internet drop boxes to arrange traditional terrorist incidents, or employing the internet to recruit young people to the cause, but because so much of our critical infrastructure is now mediated through information and communications technology war can take place entirely through the medium of cyberspace. Before addressing terrorism let me point out that the overwhelming majority of hostile incidents that occur in cyber-space are not terrorist but are cyber-crime (credit card and other financial fraud, pornography etc), cyber industrial espionage or cyber-warfare between states or state sponsored entities. The most notable feature to me is that international law has not been able to keep up with these developments and so, for example, while we are generally very clear what constitutes a de facto declaration of war on land, sea, in the air or in space, this is not the case in cyberspace. If many of the massive hostile incidents recently seen in the cyber-world had been in any of the other four spaces they would undoubtedly have been regarded as declarations of war, however the position is not clear in the fifth space. Surely one of the key developments which must take place in the near future is a focus by lawyers, diplomats, scientists and politicians on developing international and indeed global understandings that address this issue. To do this they must be more attuned to recent technical developments than I have observed is the case with most domestic legislators who simply do not understand and cannot keep up with changes in ICT, even those on which they are legislating. As far as terrorism is concerned my main concern was well described by Misha Glenny at the Second Worldwide Cyber-Security Summit at The Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre in London, in June last year. Mr Glenny, a former BBC journalist whose most recent book, Dark Market, focuses on the world of cyber-crime, pointed out that although that conference, like others, was replete with a multitude of papers, presentations and discussions on the hardware and software of cyber-security, there was very little research being reported on the psychology of cyberspace. I regard this as a major gap in the field because the way people function, as individuals and as groups and networks in cyber-space has many features that are quite different from the other four spaces and this is therefore an area to which the WFS Permanent Monitoring Panel on Motivation for Terrorism is devoting some attention. I turn now to developments in the study of more traditional terrorism. After many years of speculation and some observation about how and why terrorist campaigns commence and are sustained, more attention is now being paid to how terrorist campaigns end. As scientists we should not be satisfied with mere speculations about what might happen. We want to piece together the evidence about what actually happens, and one of the key works in this field is the study published in 2009 by Professor Audrey Kurth Cronin on ‘How Terrorism Ends’, in which she reviewed 457 terrorist organizations that had been active in running campaigns since 1968. There were a series of different outcomes, but only very rarely were the terrorists successful. Mostly they failed because of splits and in-fighting in the groups, a loss of momentum or relevance, massive state repression or decapitation of the organization through the killing or imprisonment of their leadership. In regard to this last outcome, imprisonment was generally more effective in destroying the myth of the leadership’s power, while assassination could produce martyrs to the cause. In the minority of cases where there was some degree of success, it could come about through negotiations, however most negotiations with terrorist groups, while it could delay in the ultimate end of their operations, generally reduced the death and damage they caused and usually led to them re-orientating themselves in some way, for example into democratic politics. Other forms of re-orientation were more dangerous, for example when they transitioned into organized crime (such as the narcoterrorism of FARC in Colombia and the Shining Path in Peru), or morphed into an insurgency holding of territory, developing alternative state structures, and then sometimes sliding in into more traditional civil war or overt war scenarios. This latter outcome, the destabilization of the state, is a major development for study. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries terrorism was the tactic developed by weaker groups against a powerful state apparatus, and it saw some success in the national freedom movements of the 20th century. It is arguable how far the anarchist terrorists contributed to the end of empires that was the outcome of World War I, but what is much more clear is that after World War II, with the realization of the two new super-powers that a nuclear conflict could be catastrophic, terrorist groups became a modality though which super-power rivalries could be channelled without endangering world peace. The end of the Cold War brought this phase to a close and with it some long-standing terrorist campaigns were no longer sustainable, but a new set of problems have emerged. If the tactic of terrorism was previously the strategy of the weak against powerful states, terror, chaos and massive violence as seen in many parts of Africa and increasingly in the Middle East is the result of the failure of many states to be able to sustain themselves against terrorist and other attacks and it is not clear how far this failure of states is a crisis of certain regions, or may herald a major shift towards instability and a crisis of democracy itself. The paradoxical result of the globalisation that has been facilitated by the very positive scientific and resultant technological advances in travel, transport and communications and the collapse of the stable instability of the Cold War is that people have become more anxious, not more confident. Fear about the new uncertainties of globalisation and the return of earlier crises over commodities and profound economic uncertainty have seen many people searching out the false certitudes provided by nationalism or localism which go beyond patriotism and communal pride and become characterised by populism, racism and xenophobia. Religious ideas have also come to the fore in a way which must be a surprise to those who thought that the Enlightment would lead to the inevitable end of religious faith, as our colleague, Scott Atran has pointed out in a paper in paper this month the journal Foreign Policy. Let me quote the opening lines of Scott’s paper, which are nothing if not dramatic in their implications – “The era of world struggle between the great secular ideological -isms that began with the French Revolution and lasted through the Cold War (republicanism, anarchism, socialism, fascism, communism, liberalism) is passing on to a religious stage. Across the Middle East and North Africa, religious movements are gaining social and political ground, with election victories by avowedly Islamic parties in Turkey, Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco.” This claim that we may be at a hinge of history is not related to observations in the Middle East alone. Despite years of communism in the old Soviet Union and in China, religious movements in those regions have proved profoundly resilient, and in the United States of America the place of religion in politics and government is much greater than the separation of church and state was assumed to permit. Scott’s paper goes on to point out that we should not be frightened about this because, contrary to what some believe, there is no evidence from an objective study of history that religious faith itself leads to war and internecine strife, although once conflicts start a religious tone entering in may make them more intractable. What Scott does insist, and I agree, is that instead of either ignoring or adopting religious beliefs, social scientists must try to understand them and the impact that they have in human affairs and in strategic decisionmaking at every level. This continues to be a key area of work for the PMP on Motivations for Terrorism with our work on ‘sacred values’, strategic trust and mutual influence. As I have already pointed out however the boundaries between terrorism and other tactics of warfare have become increasingly blurred with the use of terrorism and various tactics of terror by states. In this regard I must close with an expression of serious concern that goes beyond our work on terrorism, and may involve some of the rest of you. I cannot think of a time in history when there was such profound economic difficulty and dislocation which did not result in violence of a major order. Sometimes the results were seen in revolutions, at other times civil wars and of course the economic depression of the 1930’s is generally regarded as having played a role in creating the context for the terrible events of World War II. I fear that we will not escape this lesson of history. Already we have had the events of what was initially termed in the West, ‘the Arab Spring’, but which have turned out to be altogether more problematic and dangerous than was at first assumed. In addition in that region we have an on-going crisis between Iran and Israel. I am especially concerned to hear recent remarks emerging, apparently from semi-official sources, claiming that an Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities would be over in 30 days with the loss of only some 500 Israeli lives. Previous generations, living in the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and educated by some of those in this very room and other colleagues in nuclear physics, were profoundly aware that the use of nuclear weapons power was a threat to our very survival as a species - a truly planetary emergency. Knowledge is not genetic and each generation must acquire knowledge for itself, albeit learning from the work of their predecessors. I am however concerned that this generation, which forgot, and is now learning by painful experience what a previous generation knew about economic uncertainty and instability, should not have to learn with the loss of many lives, about the dangers of nuclear conflict. On this front we in the PMP on Motivations for Terrorism look to our colleagues in nuclear physics, not just to assist us in addressing the nuclear dangers posed by small terrorist groups, but to take a lead in facing up to an emergent danger at the level of inter-state conflict involving Iran or another potential or actual nuclear power. Whether in dealing with terrorism, an economic austerity whose extent is still unknown and which is likely to last a generation or more, the emerging crisis in democracy and democracies or whether in regard to the nuclear dangers which have not gone away, there are profound implications for the Erice commitment to “science in the service of humanity living at Peace” and an urgent mandate for us to find the passion, the resources and the creativity to continue our work.