The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama`s America by

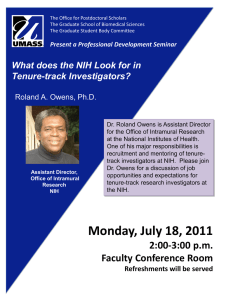

advertisement

The Race Ceiling: Book Review and Analysis of “A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America” By Jacqueline Jones Peter MacNeil History 343 Professor Ian Rocksborough-Smith 2nd December 2015 MacNeil 2 A book on race highlights a topic commonly swept under the rug in fear of evoking emotions from a scarred past. A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America by Jacqueline Jones encourages readers to explore the past lives of six people who experienced the myth of race and the detrimental effects that come with it. Ranging through historical time and place from seventeenth century colonial Maryland, to 1970s Detroit, these stories are a device for organizing a sweeping survey about the history of race in America. It is contrary to superficial appearances, a book with a strong driving thesis that informs the readers of Jones' selection of the stories and of the vast amount of historical detail of the society, which they are apart of that she weaves around the stories. One of the stories told by Jones is Simon P. Owens, who was an auto worker as well as a member of a Detroit-based Marxist humanist collective also working as a labour activist. The effects of racial formation are a constant struggle Owens faces throughout his life in the workplace. In reviewing what “race” is as being promoted as a social category, the result of social division in labour and employment can be observed. To the social force of white privilege by white factory workers fueled by the unwillingness to relinquish a history of special advantages improving their quality of life. Owens also endures the plight of underrepresentation in politics stemming into a proliferation of inequality. The unfair treatment of black workers with a union unmotivated to take action due to the historical roots of race. Moving forward to a post civil rights America promoted the false benefits of a colourblind society, breeding race division under a new name. The historical work of Jones connects 21st century America to the past, which formed the race myth predicament of today. Even though the push for "color blindness" by labour unions is viewed as lifting race categorizing for Black MacNeil 3 Americans, the biography of Simon P. Owens by Jacqueline Jones in A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America reveals not only the process of racial formation in U.S History but also the outcomes of the abuse of race in American history because of the inequality in the workplace promoting race as a social category cementing the privilege of white workers along with the lack of representation for black workers in their place of employment and at the political level. The myth of race and race politics will not disappear in the near future asserting the importance of education on the topic. The present crisis of race in the United States has led to the questioning of long accepted frameworks. The analysis by social scientists has been shaped with the understanding that a person’s colour or ancestral heritage as a concern in society is nonrational. Intellectuals and scientists have laboured to expose the falsity of popular racial conceptions that for centuries, justified oppression by white Americans to minority groups.1 The book A Dreadful Deceit not only serves as a historical retelling of six individuals living within the confines of socially constructed idea of race but also reveals it as a myth. As proposed by Jones “racial mythologies are best understood as a pretext for political and economic opportunism”2 citing race as a cultural invention instead of a biological fact. Throughout U.S. history, this invention of race has benefited a portion of the population while disenfranchising another group. Creating a unique formation and 1Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "The Theory of Racial Formation." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. 2 Jones, Jacqueline. "Introduction." In A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America. New York,: Basic Books, 2013. MacNeil 4 developmental role for race in the United States today.3 This racial formation as defined by Michael Omi and Howard Winant in Racial Formation in the United States as “the process by which social, economic, and political forces determine the content and importance of racial categories, and by which they are in turn shaped into racial meanings”4. Colonial America as a starting point integrates race and racial oppression into the larger American social structure. The colonial order in the modern world has been based on the dominance of white Westerners over non-Western people of colour. This division and oppression gives rise to a class exploitation which is fundamental in capitalists societies. In this, colonialism brought into existence the racial stratification present in the United States today.5 Labour and its exploitation must be viewed first in exploring the myth of race. From the slave plantations in the south during Boston King’s life to the factories Simon P. Owens worked in Detroit, the division of labour reflected the privileged position of white Americans. As the labour system and white supremacy were established, and the vast privileges that come with white supremacy became a high value, people of colour were controlled and dominated because they were the category chosen by whites to rule over. To ensure the elite stay above the labouring, black population is to enforce control over the inferior group. This is done through denying members of the subjugated group the full range of human possibility that exists within a society or culture. The invention of race from this standpoint highlights the historical 3 Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "The Theory of Racial Formation." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. 4 Ibid.,117 5 Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism without Racists : Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. 3rd ed. Lanham ; Toronto: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010.RR MacNeil 5 project of reducing or diminishing the humanity or manhood of the racially oppressed. For the United States, differentiating race converted the black population into objects or things to be used for the pleasure and profit of the dominant White. Further more the creation of stereotypes and the mental imagery of the colonial white population depicted blacks as animal or children to justify inhumane actions.6 In the United States “the black/white color line has historically been rigidly defined and enforced”7 proven through the historical experiences of the black population. Embracing the myth of race as a formation by the privileged is a historical theme that has continued into present day Untied States. Social categorization challenged by the people featured in Jones book. Detroit, nicknamed “Motor City” due to its long ties with the automotive industry served as a stage for the consequences of racial formation in the United States. For the black automotive worker during the boom of car manufacturing in Detroit, race and class struggles were expressed at their highest. Simon Owens, an autoworker, writer-activist and unionist in pre- and post-Civil Rights-era living in Detroit experienced this social force of being marginalized brought to life by Jaqueline Jones. In the workplace, competition for a position or promotion should be awarded to the more qualified individual, however in the factory assembly lines where Owens worked, this was not the case. In the spring of 1943, “white hate-strikers protested both the hiring and upgrading 6 Ogbar, Jeffrey Ogbonna Green. Black Power : Radical Politics and African American Identity. Reconfiguring American Political History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. 7 Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "The Theory of Racial Formation." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. MacNeil 6 of blacks”8. If there is a key to systematic privilege that undergirds a racial capitalist society, it is the special advantage of the white population in the labour market.9 It is this “special advantage” that acts as a motive for the white workers. As Jones describes it “the last refuge for whites”10 as opportunities enjoyed by white people were slipping away, protest to protect their generations of supremacy arose. Any gains made by their black coworker would come at the white’s expense. A lose would be the monopoly on jobs that are secure, clean highly skilled and involve authority with the prospect of promotion. In Owens biography this situation is displayed numerous times. From the wildcat strikes of white workers when there was an attempt to integrate three black workers as drill press workers, to the unskilled white Tennessean man receiving a position over Owens in riveting.11 The first grievance raised by Simon Owens was the working conditions of black women compared to newly hired white women who bypassed the dope room where “with the fumes of fuselage glue, workers suffered from nausea and lack of appetite”12. The white avoidance of dirty work is the linchpin of colonial labour systems. The white working class elevates their position by protecting themselves from integrating into such unpleasant work and bargain unfairly to increase their share in clean and easier jobs. Blacks were also rejected from many jobs through discrimination within the hiring 8 Jones, Jacqueline. "Simon P. Owens: A Detroit Wildcatter at the Point of Production." In A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America. New York: Basic Books, 2013. 9 Ogbar, Jeffrey Ogbonna Green. Black Power : Radical Politics and African American Identity. 10 Jones, Jacqueline. "Simon P. Owens: A Detroit Wildcatter at the Point of Production." In A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America. 11 Ibid.,255 12 Ibid.,258 MacNeil 7 process. It was not uncommon to see ads plastered across the town with the tagline “No Negros Apply”13 justified by the factory that a black worker just did not have the skill set or aptitude to do the work. This theory labeled blacks as undesirable employees. White workers, in general, viewed Black workers as lower-wage competitors who threatened the security of their jobs and the social status of their occupations rather than as working class brothers. This matter of status is apparent when white men are forced to the same general level as the former Negro slave, it represents a fixed low point for them which they cannot bare to sink to. Simon P. Owens endured this battle at the workplace for white supremacy that was unwilling to let go of a privileged history. The fifteenth amendment in the Unites States Constitution guaranteed men of African decent the right to vote in 1870. Despite the amendment, by the late 1870s, various discriminatory practices were used to prevent African Americans from exercising their right to vote, especially in Southern America.14 This sediment carried through to the time period Simon P. Owens lived and worked in. Political forces and the union set out to represent Owens played out the role of racial formation. In the history of the United States the nation was declared a “white man’s country”15 created by the norm of AngloSaxon culture shaping a culture and norms. Under this framework a system of racial politics has always taken place in the United States. In the county of Lowndes where Simon Owens was raised, suppression towards the black voter was a societal norm16. 13 Ibid., 257 Ogbar, Jeffrey Ogbonna Green. Black Power : Radical Politics and African American Identity. 15 Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "Paradigms of Race." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. 16 Jones, Jacqueline. "Simon P. Owens: A Detroit Wildcatter at the Point of Production." In A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America. 272 14 MacNeil 8 Voter registration was typically handled by county registrars, who frequently established barriers and bureaucratic restrictions such as poll taxes, literacy tests, citizenship tests and extremely limited hours and days voter registration was open. In some countries, the names and addresses of black voters were published in the local newspapers, leading to almost inevitable harassment, intimidation, violence, lynching and/or job loss. As a result, in many parts of the South, there were few registered black voters and subsequently, almost no political power. Owens became active in his former home county of Lowndes in the 1960s to assist with voter suppression of blacks and was even recognized in an article as “Lowndes Northern Guardian Angel”17. To gain power and a voice in the political sphere a representative that advocates for the intimidated minority is essential. Interestingly enough, Owens cited race as a useless categorization to distract from a more suppressing issue in hand, the division of labour and capitalism.18 This is echoed in his novel “Indignant Heart: A Black Workers’ Journal” written under the pen name Charles Denby which demonstrates existence within a white supremacist, patriarchal capitalist society comes at the cost of unceasing battle against the relations that aim to objectify the black worker.19 Politicians such as George Wallace a three time Presidential candidate and former governor of Alabama became famous for statements such as “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!”20 Wallace was promising that he would stand-alone for the Southern cause and the cause of 17 Ibid.,274 Ibid., 277 19 Denby, Charles. Indignant Heart : A Black Worker's Journal. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1979. 18 20 Frederick, Jeff. Stand up for Alabama Governor George Wallace. Modern South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007. MacNeil 9 the white people. As Wallace aimed for the White house he posed a problem for Owens, as he developed his campaign he further to drove a divide between American people. As Owens sat in on a Wallace rally in Detroit in 1968 he “rallied his white working class supporters … yelled about law and order” bringing Owens to the conclusion he was a fascist. This fight to reduce practices of Gerrymandering and voter suppression showed “ultimately, the principles of justice and fair play counted for more than some kind of essentialist politics based on skin color”21In this sense, race and the process of racial formation have important political and economic implications. “Workers Unite!” so long as you can mold to certain criteria’s of an essential worker. This form of discrimination came from within Simon Owens workplace just as it did from many other employers of black Americans. The anti-black hostility in the American labour movement has deep historical roots demonstrated in"Simon P. Owens: A Detroit Wildcatter at the Point of Production." as early as the 1960’s. Contrary to the image of unions as promoters of interracial unity and class solidarity, their history demonstrates that they are exclusive to people of colour and share the same racist values and attitudes as the majority of American society. Referring back to Owen’s advocacy for the betterment of working conditions in the “Dope Room” the committee member who he worked with, a black man named Bill Oliver, appeared to betray his own “race” by positioning himself with higher ups shielding himself from the true conflicts.22 The Union Owens was at odds with was the United Auto Workers union, one of the most powerful unions in the country. The UAW, a sole bargainer for workers in the automotive 21 Jones, Jacqueline. "Simon P. Owens: A Detroit Wildcatter at the Point of Production." In A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America. 257 22 Ibid., 258 MacNeil 10 industry, shifted the employees working environment with labour movements. Though unions focus on collective action Owen’s struggled to believe there was a self-proclaimed “Culture of unity”23 as black workers were excluded from neighbourhoods, restaurants and even bowling leagues that were enjoyed by white members. Without microinteraction and representation in these social settings how could the black worker be seen as a part of the collective action? Jones cites that during Owen’s career, the “UAW refused to acknowledge the particularly vulnerable status of black workers”,24 this is in part because while leadership was willing to hire black organizers as permanent staff, organizers were frustrated by the reality that although white union officials recognized there was discrimination, they had a “go slow” attitude because they did not want to lose the loyalty of white autoworkers, particularly Southerners with racist views. It was the newly arrived Southerners who were given preference for jobs at the plants over blacks who lived in Detroit and had been trying to become active participants in society.25 Owens was declared a wave maker as a worker when he ran to sit a committee member, seeking to wipe out favouritism and reward seniority not only for black workers but all workers in the shop.26 Breaking ranks from the classification of race Owens was guided by the desire to have all social divisions truly represented in the Workers Union. Owens had to challenge the Union and management that was riddled with “white racists in both”27. As black workers, advocacy groups referred to UAW as “U-Ain’t-White”, the historical ploy to cater to union members with white privilege serving as a tool to gain 23 Ibid.,260 Ibid.,261 25 Ibid.,270 26 Ibid.,272 27 Ibid.,279 24 MacNeil 11 support and rectify the grievances of black workers. Through this the union acted as an agent of racial formation in being a social forces to stunt the growth of black’s rights. The radical 1960’s promised great change for the American individual and their rights. The introduction of civil rights legislature in the United States promoted the end of legal sanctions and discriminating hiring for the disenfranchisement of blacks.28 For black Americans “The civil rights movement sought not to survive racial oppression but to overthrow it”29 with the prospect of not only having rights but also power. As the idea of a “colorblind society” emerged where colorblindness is the racial ideology that posits the best way to end discrimination is by treating individuals as equally as possible, without regard to race, culture, or ethnicity.30 For Owens this version of equality seemed more of a flourish compared to a true solution. Colorblindness creates a society that denies their negative racial experiences, rejects their cultural heritage, and invalidates their unique perspectives.31 This ideology became a tool to maintain racial order in a post civil-rights institutionalized system maintaining white privilege without fanfare. As Jones describes in Owens life, post civil rights movement, many blacks were given the opportunity to work in new roles such as black women fulfilling clerical roles and black men in the south obtaining textile factory jobs, but the reality of the chains of racial formation were still present.32 Colour blindness does not foster equality or respect; it 28 Ibid., 279 Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "The Great Transformation." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. 30 Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism without Racists : Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. 31 Ibid., 5 32 Jones, Jacqueline. "Simon P. Owens: A Detroit Wildcatter at the Point of Production." In A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America 277 29 MacNeil 12 merely relieves society from the obligation to address important racial differences and difficulties. Owens disregarded this notion that new legislation would equalize the workplace but rather believed that “blacks and whites working together could bring about meaningful transformations that were at the heart of a real political movement”33. The social construction of race is a matter of both cultural repetition and material relations which the ideology of colour blindness has limited or no power removing. The pledge of allegiance recited in schools across America ends with the powerful line “ one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all”34. The book, A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America by historian Jacqueline Jones shows “liberty and justice for all” was not the case for many black Americans. The history of race in the United States can be truly understood by the lives defined by it. Jones contributes, through her historical analysis regarding the myth of race in the United States, that in a racial and colonial capitalist society where racially oppressed are the minority, the creation of race will not be overcome when the majority actually benefits from suppression. The other factor being those with white privilege will defend their privileges as rational and objective interests. The importance of educating the population on the history of race in the United States resounds loudly in Jones’ historical research. Stated in the epilogue the willful ignorance of Americans to be “indifferent to, the history that produced concentrated populations of improvised black 33 Ibid.,274 "Pledge of Allegiance." Dictionary of American History. 2003. Encyclopedia.com. (December 5th, 2015).http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G23401803289.html 34 MacNeil 13 people”35. The belief that the United States is a post-racial society is false notion as a person’s racial identity largely impacts their culture, politics and economic status. In other words “The concept of race continues to play a fundamental role in structuring and representing the social world”36. Jones challenges the reader to view racial inequalities as rather class inequalities with long historical roots. In highlighting the gains made by evoking the myth of race, Jones contributes to the history of winners and losers of a capitalist system. The colour of one’s skin is not a choice but rather a biological factor. The historical retelling of six individuals linked by their skin colour and the governing forces, which they live under, provides a true insight to the concept of race as a myth. Jacqueline Jones’ well-written and informative historical bibliographies demonstrate race as power relations. Simon P. Owens in “A Detroit Wildcatter at the Point of Production” experienced this through his life growing up in the Southern United States to working the assembly lines in Detroit. As the social force of white privilege held back black workers, like him, from promotions and opportunities, the political force of underrepresentation was at play. The union set up to represent Owens and black workers surrendered to the ideology of white workers that aimed to hold onto their superior privilege. Moving forward to a post civil rights era where colour blindness is encouraged, but barley scratches at the surface of the inequalities at hand. A Dreadful Deceit by Jacqueline Jones demonstrates racial formation and the outcomes of the abuse of race in writing the life 35 Jones, Jacqueline. "Epilogue." In A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America 2 36 Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "The Theory of Racial Formation." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. MacNeil 14 story of autoworker Simon P. Owens. If the myth of race continues to be evoked in America when will all people regardless of their background be full and equal citizens? MacNeil 15 Bibliography Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism without Racists : Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. 3rd ed. Lanham ; Toronto: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010. Denby, Charles. Indignant Heart : A Black Worker's Journal. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1979. Frederick, Jeff. Stand up for Alabama Governor George Wallace. Modern South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007. Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. Unequal Freedom How Race and Gender Shaped American Citizenship and Labor. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002. Jones, Jacqueline, and Ebooks Corporation. A Dreadful Deceit : The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama's America. New York: Basic Books, 2013. Ogbar, Jeffrey Ogbonna Green. Black Power : Radical Politics and African American Identity. Reconfiguring American Political History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "The Theory of Racial Formation." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "Paradigms of Race." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. "The Great Transformation." In Racial Formation in the United States. Third ed. 2015. Peterson, Joyce Shaw. "Black Automobile Workers in Detroit, 1910-1930." The Journal of Negro History 64, no. 3 (1979): 177-90. "Pledge of Allegiance." Dictionary of American History. 2003. Encyclopedia.com. (December 5th, 2015).http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3401803289.html