The River, Freedom, and Huck Finn

advertisement

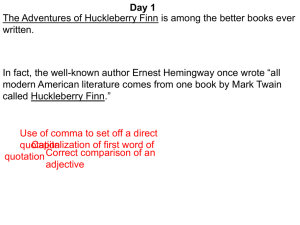

Orth 1 Stephen M. Orth, 1995. The River, Freedom, and Huck's Happiness in Facing the Absurd: An Existential Approach to Huckleberry Finn Huckleberry Finn, first published in 1884, is clearly Mark Twain's masterpiece. Interestingly, however, it is considered by many critics to be a precursor to works of disillusionment which Twain would later produce in years of pessimism and bitterness. Huckleberry Finn signals, perhaps, the beginning of Mark Twain's disenchantment with mankind and society. A well known theme of the novel, the relationship between the "corruption" of society embodied by the shore and the "freedom" of the river, supports this theory. I will take a less conventional approach to symbolism of the river and the shore, however, and examine Huck's freedom in light of basic existentialist thought. Clearly Huckleberry Finn is not an existential novel. Nevertheless, there seems to be a significant thread of existential thought interwoven throughout Twain's realism. First, a rough definition of existentialism is needed. Existentialism is concerned, at its most basic level, with the affirmation of freedom and the refusal to subordinate personal awareness to abstract concepts and dehumanizing social structures. It represents rebellion against established ideas and institutions which inhibit personal freedom. Existentialists realize they are free to create themselves through their own actions. However, in the creation of the self, one is always limited by an inevitable death and, thus, life becomes meaningless, or what Albert Camus calls absurd. As Camus suggests in his essay, "The Myth of Sisyphus," revolt from the absurd gives life its value. Camus comments, "what counts is not the best living but the most living."i Revolt from the absurd, then, is the freedom to create the self. Huckleberry Finn, like the existentialist, finds himself facing the void of a meaningless life. He tries to take action and choose his own destiny, but he is instead manipulated by the actions of others and, most often, left powerless to create himself. The river, then, does not represent true freedom; for, there are times on the river when Huck is not truly free to choose his own actions. However, there are instances, intermixed with such periods of "non-freedom," when Huck does have Orth 2 the opportunity to create his own destiny. And, as I will demonstrate, it is during these periods of true existential freedom on the river that Huck is able to find happiness in facing the absurd. Huck has clearly noted the meaninglessness of life, and this fact is evident in his obsession with death. Huck is constantly preoccupied with death. In the first chapter of the novel, Huck, trapped in the Widow's grip, states: "I felt so lonesome I most wished I was dead"(9).ii In addition, Huck often makes numerous references to death in general. For example, he hears an owl "who-whooing about somebody that was dead, and a whippowill and a dog crying about somebody that was going to die"(9). Or, there are times when Huck suggests that being dead is much better than being alive, such as during Peter Wilks's funeral when Huck comments: "Peter was the only one that had a good thing, according to my notion"(144). Peter Beidler suggests that Huck's obsessive concern with death is the result of his desire for it.iii Indeed, throughout the novel, Huck often wishes for death. Huck's longing for death is usually the result of society invading his conscience, as when he reconsiders helping Jim to escape: "I got to feeling so mean and miserable I most wished I was dead"(73). Or, upon arriving at the Phelps's farm, Huck comments on the lonesomeness which "makes a body wish he was dead, too, and done with it all"(173). A few sentences later Huck states "I knowed for certain I wished I was dead." Huck, unlike the existentialist facing the absurd, sees death as a means of gaining ultimate freedom. In order to escape from the bounds of civilization, Huck is forced to "take" his own life. As Beidler suggests, Huck's faked death is more an expression of his own desire for death than of any real fear of being followed by Pap or the widow.iv However, throughout the pages of the novel, Huck remains very much alive. And thus, Huck, like the existentialist, is forced to flee from those elements of life which inhibit his freedom. The first such element is represented by the society of the widow. Although Huck has begun to accustom himself to the widow's way of life, he escapes the widow's dehumanizing social structure when he is kidnapped by Pap, and he finds he enjoys the new freedom: Orth 3 It was kind of lazy and jolly, laying off comfortable all day, smoking and fishing, and no books nor study...I didn't see how I ever got to like it so well at the widow's, where you had to wash, and eat on a plate, and comb up...I didn't want to go back no more. (24) However, Huck is soon faced with another inhibition of his freedom, Pap's brutality. This time Huck takes destiny into his own hands and makes his escape. Huck's joy in escaping from the shackles of society is immense. Such elation is evident in his enjoyment of the easy living which Jackson Island and the raft represent and comments such as, "Take it all around, we lived pretty high"(56). However, as Leo Levy points out, the passages which are understood to exemplify this liberating experience--the idyll of drifting on the raft with Jim and the eloquent hymns to nature in chapters IX and XIX--do not concretely symbolize the contrast between "civilization" and "freedom".v Clearly Huck cannot be said to be entirely free, for his conscience is still full of anxiety and guilt for helping Jim escape. It is important to note that although the river may symbolize freedom, Huck rarely experiences complete freedom on the river. Instead, Huck's journey down-river consists of periods of freedom and non-freedom. Interestingly, the most striking of the pastoral, or "free", episodes on the river are often intermixed with grim and contemptible events, such as the arrival of the King and the Duke.vi For example, their appearance is preceded by particularly beautiful, pastoral imagery in which Huck and Jim revel in the loneliness and freedom of nature: And afterwards we would watch the lonesomeness of the river, and kind of lazy along, and by-and-by lazy off to sleep...So we would put in the day, lazying around, listening to the stillness. (97) At the King and Duke's arrival, however, Huck and Jim once again find themselves in society's grasp. In this manner, then, Huck is constantly limited from choosing his own destiny. Huck tries to determine his own self but he cannot always do so. His choices are blocked because of the actions of others, actions which are beyond his control. Thus, the river as a symbol of freedom cannot be as clearly defined as some readers believe it to be.vii Huck's true freedom is present Orth 4 only for brief periods on the river, when he is alone with Jim. During these moments, Huck is able to face the void of a meaningless life and revel in its loneliness. As Paul Schacht points out, Jim's company gives Huck shelter from that something in Nature which speaks mournfully and even urges Huck toward death.viii That is, instead of being overwhelmed by the lonesomeness of the river, Huck, through Jim's companionship, can find happiness in the freedom of the river; he can find happiness facing the absurd. After Huck has transcended his conscience, as indicated by his exclamation, "'All right, then, I'll go to hell,'"(169) he has chosen, like the existentialist, to cast off the conventions of society and create his own self. He has refused to let his guilt determine his actions. Now, Huck can face the void and not fall totally into despair. As Schacht suggests, the river invokes in Huck the same sense of isolation and loneliness that he felt at the widow's and at the Phelps's farm.ix But now, because of Jim's friendship, Huck does not feel lonely. The freedom of the river becomes delightful to him and its lonesomeness becomes an object of aesthetic contemplation. The reader, at these moments, then, can imagine Huck happy in facing the absurd. For an example of such a moment in which Huck experiences true freedom, I refer to the passage when Huck and Jim have just shoved off from the Grangerford's, escaping the absurdity of the feuds: I was powerful glad to get away from the feuds, and so was Jim to get away from the swamp. We said there warn't no home like a raft, after all. Other places do seem so cramped up and smothery, but a raft don't. You feel mighty free and easy and comfortable on a raft. (96) It is here that Huck most clearly exhibits the existential freedom of choice. He has chosen his own destiny, and what results is a freedom in which he is content with life. This freedom is short lived, however, as the appearance of the King and the Duke follows, and Huck again is forced to sacrifice his freedom. However, another such moment of true freedom arises when Huck and Jim think they have shaken the King and the Duke: "So, in two seconds, away we went, a sliding down the river, and Orth 5 it did seem so good to be free again and all by ourselves on the big river and nobody to bother us"(162). Of course, this freedom does not last long as the threat of civilization upon Huck's self reappears, and Huck again feels the despair of the void: "So I wilted right down onto the planks, then, and give up: and it was all I could do to keep from crying"(163). And so, the pattern of freedom followed by un-freedom repeats once again. Clearly though, it is during these brief moments of freedom in which Huck is actually happy and has control of his life; it is during these moments which Huck truly lives. Ironically, as the novel ends, Jim finally attains the type of freedom he has been seeking all along, legal freedom. Huck's quest for freedom, or a life free from restrictions, however, cannot end.x Huck tells the reader he has to: "light out for the Territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilize me and I can't stand it"(229). Once again, the reader finds the pattern repeating: Surely, Huck will escape the bonds of civilization in the Territory, but his escape will be short-lived. For, civilization, in the form of some Duke or Aunt, will catch up with him. Huck will continue to remain in stasis, always close to self-creation, but never actually able to attain it. In contemplating Huck's periods of freedom and non-freedom, I cannot help but think of Albert Camus's interpretation of the Myth of Sisyphusxi. Sisyphus's torment is never ending. Each time he reaches the summit of the hill with his stone, it rolls downward again. However, it is during this return, the pause in which the stone rolls backward, in which Camus interprets Sisyphus to be happy. As Camus states, "for Sisyphus, that moment is like a breathing space which returns as surely as his suffering; it is Sisyphus's hour of consciousness."xii Therefore, it can be said that Huck also enjoys a similar "breathing space" in his moments of freedom. The pause, in the periods of true freedom on the river, is Huck's hour of consciousness. Thus, one must assume, Huck, like Sisyphus, finds happiness in his hour of consciousness, and that he is, after all, happy. And thankfully, Huck, unlike Sisyphus, has only to endure the torments of civilization until the moment of his inevitable death. Orth 6 iCamus, "The Myth of Sisyphus," p61. Samuel. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1977. iiiBeidler, in "The Raft Episode in Huckleberry Finn," closely examines Huck's obsession with death, p247. ivBeidler, p248. vLevy, in "Society and Conscience in Huckleberry Finn," explains how he believes some critics have pressed the pastoral images of the river too hard as exemplifying the "freedom" of the river, p386. viLevy, p387. viiLevy accuses Leo Marx, in particular, of misinterpreting Huck as being "entirely free of anxiety and guilt" on the river, p386-7. viiiSchacht, in "The Lonesomeness of Huckleberry Finn," discusses the relationship between Huck's loneliness and the lonesomeness Huck sees in nature. Schacht believes that, because of Jim's love, Huck is able to find peace in the lonesomeness of nature, p197. ixSchacht, p198. xSchacht notes this ironic twist between Huck and Jim's freedom, p200. xiCamus, p121. Sisyphus, a figure of Greek mythology, had been condemned by the Gods to ceaselessly roll a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. xiiCamus, p121. iiClemens, Works Cited Beidler, Peter G. "The Raft Episode in Huckleberry Finn." In Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Sculley Bradley, ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1977, 241-250. Eliot, T.S. [An Introduction to Huckleberry Finn.] In Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Sculley Bradley, ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1977, 328-335. Camus, Albert. Alfred A. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays. New York: Knopf, 1964. Levy, Leo B. "Society and Conscience in Huckleberry Finn." Nineteenth-Century Fiction, XVII (March 1964), 383-391. Marx, Leo. "The Pilot and the Passenger: Landscape Conventions and the Style of Huckleberry Finn," American Literature, 28(May 1956), 129-146. Schacht, Paul. "The Lonesomeness of Huckleberry Finn," American Literature, 53 (May 1981), 189-201. Orth 7