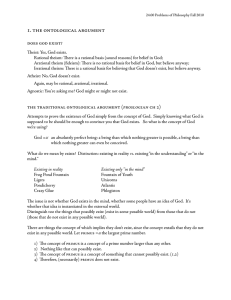

God-exists

advertisement

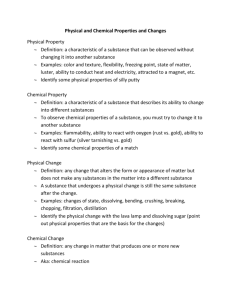

The Catholic Tradition: Which God don't you believe in? "I don't believe in God?" "God does not exist." What do people mean when they say these things? Often, people who say this do not really understand what Catholics mean by the proposition "God exists." So, when dealing with atheists, it becomes very important to clarify, "What do you mean by God?" What do you mean by "exist?" You may find out that the atheist is rejecting a phantom, a "god" Catholics also reject. Let me illustrate. I read once about a camp for children run by atheists. Their goal was to inoculate children against religious belief, and they used a number of techniques. One stuck in my memory. The children were given the task of proving that unicorns do not exist. Once you begin the task, you realize it is impossible. There is no way to prove that unicorns don't exist. The best you can do is show that there is no good reason to believe in unicorns. The point of the exercise should be obvious. The camp counselors wanted the children to think of God (or the gods) like unicorns: mythical beings for whom there is no scientific or empirical evidence. The problem with this plan is that it totally misrepresents what Catholics mean by the word "God." Catholic philosophers go to great pains to explain that God is not a being among other beings. He does not belong to the genus or class "things that exist." In fact, he is not in any genus or class at all. (For example, see St. Thomas Summa theologica I. 3.5.) If there were a unicorn, it would be one thing among many - like a squirrel, or a fish, or a stone. Similarly, if the Greek gods existed (Zeus, Hera, Hercules), they would also be things, substances, beings. But, St. Thomas says, this does not at all capture what we mean by the word God. The unicorn exercise also misrepresents what we mean by exists. Many atheists assume that there is only one way that a thing can exist - by taking up space, the way a unicorn in the forest would take up space (and be susceptible to scientific investigation) if it were to exist. This is what Aristotle would have called a substance. But this is clearly not the only way we can think of existence. Consider the following: Numerical relations are real - they exist - in a way, but not in the way a cat or a unicorn would exist. Numerical relations are abstract entities. Attributes or qualities (accidents) are also real things like tall, green, round - but they exists differently from substances. The Mind is real - a conscious entity constituted by concepts, intentions, reasons, memory and personal identity, but the mind does not exist at all in the same way that bricks or dogs or even hearts and livers exists. Minds depend on matter (the brain) for their operation, but they cannot be reduced to matter. The mind is an immaterial reality- (If you doubt this, try explaining how mental concepts like democracy, or the quadratic formula, or logical operations are material entities.) These distinctions are very important when we explain to atheists what we mean by the words "God exists." At the very least, when we say "God" we mean the ultimate explanation of all beings, the ground of their intelligibility. And so to say, "I don't believe in God" is as much to say, "I don't think that reality is intelligible. There are no ultimate explanations. Reality is absurd." Most modern atheists (with their love of science) are not willing to go there. The real debate, therefore, is not such much whether God (so defined) exists, but what God is like? Is ultimate reality (God) complex, material, and random? Or is it immaterial, simple (indivisible), and purposeful? Likewise, when we say that God exists - we do not mean that he exists in the manner of a material substance. Material substances are subject to change, they are composed of parts, and they depend on a certain bodily integrity or form for their existence. (To illustrate, if you smash a cat into something shaped like a pancake, it stops being a cat.) But this is not what exists means when applied to God. God's existence is more like (but not exactly like) that of minds and abstract entities. In technical terms, we speak of God as Subsistent Being - not a being, but the ground of all being, the ultimate fact or reason for finite beings. Proving the existence of God (so defined) boils down to showing that material substances cannot be the source of their own existence. They depend, here and now, on deeper and deeper layers of reality that become less and less like material substances the more you investigate them. Even an infinite number of material substances in a causal chain would still depend on deeper realities like being and causation itself - to explain their existence. This reflection leads us to a reality that is not subject to change (for there is nothing prior that could cause it to change), that is simple, that has no parts (for there is nothing prior that could explain its composition), and that is purposeful or goal-directed - inasmuch as reality proceeds from it as a consistent effect from a cause. We are led to a reality in which existence itself does not depend on form (the way a cat depends on cat-form to exist), but to a reality in which being and essence are one. What do you mean by God? What do you mean by exist? Our philosophical answer to these questions does not bring us all the way to the God of Catholic Christianity. There are still many things that Catholics believe that cannot be proved by reason. But the Catholic doctrine of God presupposes the philosophical definition. (So says the First Vatican Council.) We cannot have a rational discussion with an atheist if we don't understand this. In some cases, the atheist has never really considered the case for God. He is rejecting a God we dont' believe in either. Only after we establish this can we move on to considering the case for Catholic revelation.