References - MacSphere

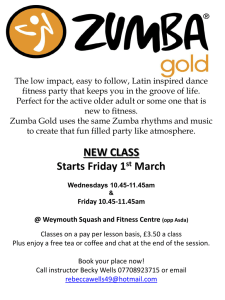

advertisement