Elder Christofferson Freedmen`s Bureau Final

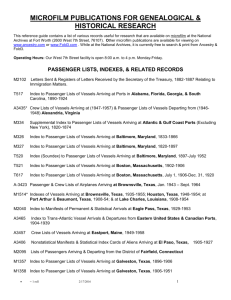

advertisement

Elder D. Todd Christofferson Remarks Freedmen’s Bureau Project Announcement California African American Museum Los Angeles, California June 19, 2015 Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Let me begin by saying, in the wake of the tragic shooting in Charleston, South Carolina, Wednesday night, our prayers are with the families of the victims and with the members of the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston. We pray that all who mourn may find the peace that comes only from God. There, unfortunately, regrettably we saw hate. Here today we’ll talk about love. Fourteen years ago I stood at a similar podium in Salt Lake City, Utah, as I participated in another announcement concerning African American genealogy, the completed index of the Freedman’s Bank Records. Paul and Gaye Cobb were there, along with a number of others who are also here today. The Freedman’s Bank was created to help newly freed former slaves with their new financial opportunities and responsibilities. In an effort to establish the identities of bank patrons, workers at the time recorded the names and family relationships of account holders, sometimes taking brief oral histories. Although the bank tragically collapsed because of mismanagement and fraud, the records it had provided a treasure trove of valuable family history information. I was then the Executive Director of the Family and Church History Department for our faith, and I witnessed the healing and joy that African Americans experienced as they discovered their ancestors for the first time in those records. Today, I am humbled once again to be a part of a historic announcement that can—on paper— potentially reunite the black family that was once torn apart by slavery. Happily, this time the records are 10 times greater, comprising an estimated four million names. And this time the black community is uniting to help create a wonderful tool with which to discover its own family. Let me tell you briefly about these records, records which take us back as a nation to the turbulent time at the conclusion of the Civil War. In 1865, newly freed men and women had a chance to reunite their families, to create communities, and to participate in their own government. But they also faced immense obstacles and so the federal government created the Freedmen's Bureau to facilitate their transition to citizenship. The Bureau helped reunite families, opened schools to educate the illiterate, managed hospitals, supervised labor contracts, rationed food and clothing, and even formalized marriages. In the process, the Bureau gathered priceless handwritten, personal information on African Americans. In total, the Bureau’s records comprise over 1,100 rolls of microfilm with untold stories of African Americans immediately following emancipation. These are personal, sometimes difficult accounts to read from a turning point in our nation’s history when our forebearers were struggling with their own humanity. But what one also sees in these records is triumph and hope and resilience. What a great testimony to the sheer will and determination of this generation of people who had so little, yet rose to freedom and dignity. The Freedmen’s Bureau records are the property of the National Archives and Records Administration, which has carefully preserved and protected them for the American people. We honor its commitment to the past. FamilySearch, a nonprofit organization sponsored by our faith, purchased copies of these records from the National Archives in order to index and publish them digitally. In addition, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is slated to open on the Washington Mall next year in 2016, is partnering with FamilySearch International to index the records and to make this searchable database accessible online as well as in a family history center that will be part of that new museum. Now, we are calling this the Freedmen’s Bureau Project for a reason. Although the images of the records are now available on discoverfreedmen.org, they have not been indexed—meaning the key information such as names, dates, and places have not been extracted and put in an index so that the records can be searched. Today you are going to hear more about the project to index these records so that African Americans can find their families from the Civil War era, many for the first time in history. So why is our faith so involved in genealogy? One of our key beliefs is that our families can be linked forever and that knowing the sacrifices, the joys, the paths our ancestors trod, helps us to know who we are and what we can accomplish. For over 100 years, FamilySearch and its predecessors have been actively gathering, preserving, and sharing genealogical records. Today, a dedicated team of employees and volunteers works tirelessly to preserve and share the largest collection of genealogical and historical records in the world for all of God’s children. It is our hope that the Freedman’s Bureau records will be a valuable resource for African Americans and help link together families so long and tragically separated. I would now like to show you a short video, illustrating the Freedmen’s Bureau Project and the significance of these records.